Disclaimer for References to Greenhouse Gas in this document:

On January 20, 2025, President Trump signed Executive Order (E.O.) 14148 --Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions and E.O. 14154 – Unleashing American Energy. The E.O.s revoked E.O. 13990 – Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis (January 20, 2021) and E.O. 14008 – Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad (January 27, 2021). Subsequently on January 29, 2025, Secretary Duffy signed a Memorandum for Secretarial Offices and Heads of Operating Administrations – Implementation of Executive Orders Addressing Energy, Climate Change, Diversity, and Gender. On February 25, 2025, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) published an Interim Final Rule removing the CEQ’s National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) implementing regulations, effective April 11, 2025 (90 Fed. Reg. 10610). As a result of these actions, FHWA will not include greenhouse gas emissions and climate change analyses in the federal environmental review process. Any purported greenhouse gas emissions and climate change impacts will not be considered in the federal decision.

Ecosystem and Vegetation Management

VEGETATION MANAGEMENT: An Ecoregional Approach

View PDF (14 MB)

Edited by

Bonnie Harper-Lore, retired FHWA Restoration Ecologist

Maggie Johnson, EPA Botanist

William F. Ostrum, FHWA Environmental Specialist

CONTENTS

FOREWARD

When we first started using an “ecoregional approach” to roadside vegetation management, we received an inquiry from a newspaper in the Minneapolis-St.

Paul area. They wanted to know why we weren’t mowing and spraying more (or all) of the non-paved areas of the transportation corridors. Our response was

that roadsides fit the definition of rangelands or grasslands, even where largely wooded. The roadsides are not agricultural lands, manicured lawns nor

parklands. Rangelands are mainly managed by applying ecological principles to the development and manipulation of the vegetation. An ecological approach

required a longer time frame to produce favorable results. A newspaper responded that it sounded good but seemed to be just another name for “don’t

mow the grass and let the weeds grow.” And so it often may appear at first. Time is an important element in the development of things in nature.

Starting from zero in 1900, independent motorized vehicles (cars and trucks) increased so rapidly that by about 1930 there was one car for every six citizens

(today there is more than one per citizen). Highway structures had to increase accordingly and became the “Arteries of the Nation.” They are

the most widespread and visible of all public improvements. In 1932, the Roadside Development Committee in the Design Division of the Highway Research

Board was established to research and disseminate information regarding roadside care and use (termed “development”). Later there was a Committee

on Roadside Maintenance in the Maintenance Division. In time, the American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) formed a somewhat parallel committee

to exchange information on the subject between the States. In the late 1960’s, the AASHO committee was re-established in a different form and name.

With the “Great Depression” in the 1930’s, highway work projects of the Works Project Administration (WPA) employed many architects and landscape

architects. It was natural that a “dressed-manicured” agronomic approach should result. The term “front yards of the nation” came

into vogue. This carried with it the image of front lawns, fairways and parkways (as per the Washington and Taconic Parkways) developed at that time.

The agronomic approach was in the forefront.

With the start of the Interstate highway program, late 1950’s, early 1960’s, the acreage involved rapidly increased and so did soil erosion and costs.

By the late 1960’s roadside policy modifications became common - “limited contours” and “architectural mowing” and spot spraying

are examples. Then in the 1970’s came the fuel shortages and cost inflation to increase the mood for change. Applications of the ecological approach were

showing results and gaining public acceptance.

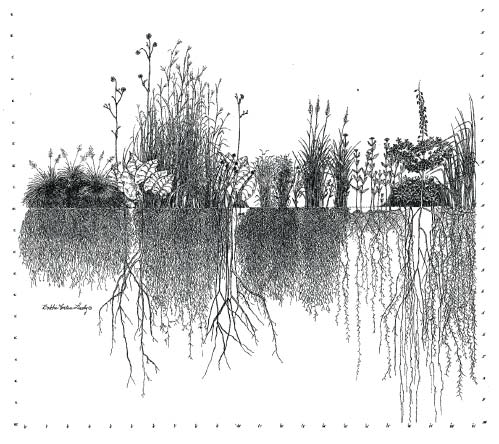

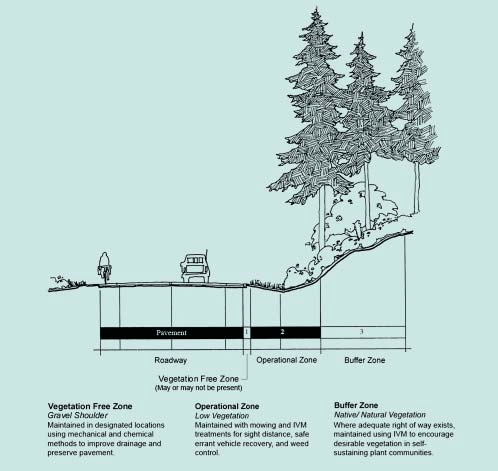

The transportation structure exists between the two right-of-way boundaries. Its primary purpose is to provide a safe, smooth, solid surfaced area to

move vehicles on efficiently. All other concerns are secondary or less. Thus the main purpose of the non-surfaced areas i.e., fore slope, ditch, back

slope and other vegetated areas - is to provide stability to and protection for the surfaced areas from damage or traffic interruption. The ecological

approach is a naturally stabilizing approach for vegetation whereas the agronomic approach is a disturbing approach (mowing, broadcast spraying with the

negative effects of the accompanying power equipment).

The two approaches, ecological and agronomic, require a differing set of inputs. the ecological approach mainly requires research and planning with some

minor material, equipment and financial inputs such as seed, spot spraying and limited mowing. The agronomic, approach required large inputs of equipment,

materials, manpower, fuel and finances. the agronomic approach has quick, short-lasting results (a freshly-mowed area, for example). Because of the disturbance

resulting to vegetation from the mowing, spraying, etc. the results are short-lived and must be repeated regularly. Damage from the equipment (wheel tracks,

etc.) is longer lasting. The results of the ecological approach are considerably slower from decreased disturbance, and increased vegetation stability

is large. Secondary dividends are increased habitat for small non-game and game wildlife, refuges for native plant species and often a pleasing visual

appearance. Some call it “naturalization of the roadside”.

Lawrence E. Foote, Ph.D.

retired, Minnesota Department of Transportation

Back to top

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Vegetation Management: An Ecoregional Approach is the third book in a series intended to provide support for the on-the-ground individuals of State Departments

of Transportation (DOT) and other land managers as partners. Once again we called upon many scientists and practitioners to help us fill in the blanks.

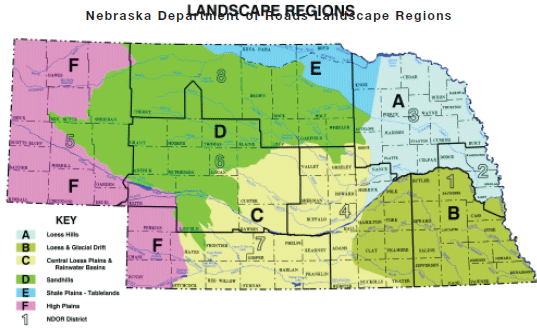

State DOTs’ help was given by Jeff Caster (prescribed burn and outdoor advertising), Kenneth Graeve (native seed mix), Tina Markesson (bio-control use),

James Merriman (protection of pollinators), Art Thompson (the Nebraska model), and Ray Willard (corridor functional zone graphic). State Departments of

Natural Resources and their Natural Heritage Programs provided the ecoregion maps and visitable sites. Carmelita Nelson from the Minnesota DNR contributed

greatly to the section on road-sides for wildlife.

Coincidentally a National Cooperative Highway Research Program 14-16 project with the Transportation Research Board overlapped this work in 2009. We thank

Ian Heap, lead investigator on that team, for sharing the specific weed controls for 40 species of common invasive plants, often found on noxious weed

lists. Another research project is reflected in the section on GPS use in inventory work. Thanks to Victor Maddox of Mississippi State University for

the applied research and the training manual we hope all States will utilize.

Thanks to the support of the Federal Highway Administration’s Divisions and Resource Centers’ review of the classroom exercises. They are in perfect position

between Washington D.C. headquarters and the work on the ground, to review applications of this training manual. A very special thanks to our Natural

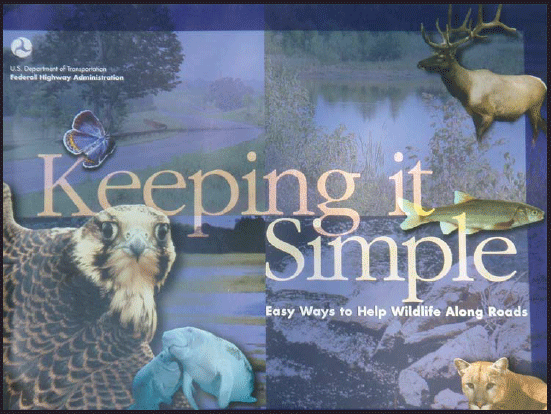

Environment teammates who reviewed information on the Migratory Bird Act, erosion and sediment control, wildlife habitat, along with roadside vegetation

and deer-crashes.

Our respect and appreciation go to Kirk Henderson of the National Center for Roadside Vegetation in Cedar Falls, Iowa, for his input into Part 3: Native

Plant Establishment. The Iowa experience with native plantings, expanding production of native ecotype seed and natural selection, along with the legislated

Iowa Living Roadside Trust accomplishments, should be a model to all States.

Including the foreword by Dr. Lawrence Foote is a great honor. He foresaw the potential for conservation and restoration of corridors. Our thanks for

his contribution.

We also thank Maggie Johnson (USEPA, Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention (OCSPP) at headquarters in Washington, DC) for her diligent and

meticulous work. Without Maggie’s communications with all 50 state Natural Heritage Programs, this unique collection of ecoregion maps would not exist.

And I thank Gary Lore for his unpaid editing time. No one does it better!

Bonnie L. Harper-Lore

Restoration Ecologist

retired, FHWA

Back to top

INTRODUCTION

Highway corridors connect us all via our commercial transport, recreational excursions, workday travel, and more. The mobility and safety of U.S. highways

is a proud accomplishment of the Federal Highway Administration with its State and local partners. Highway rights-of-way are the most visible of all public

lands and likely the least understood. This manual is especially written for those decision-makers in maintenance, landscape, environmental services,

and turf and erosion control to share what we know about managing this land.

The world of roadside management is complicated. Environmental regulations limit the practices we use. Utility lines, signage, fiberoptic and oil pipelines,

snow storage, adjacent crops, trout streams, and rangelands further limit our solutions. Daily weather conditions require changes on the fly. Public expectation

can change everything. Roadside development and maintenance have evolved far beyond the simple mow and spray or agricultural approach of the 1930s and

’40s.

In 1932, the Highway Research Board and American Association of State Highway Officials began the Committee on Roadside Development. The Bureau of Public

Roads (now the Federal Highway Administration) helped inspire a nation-wide interest in roadsides. Within this Committee were research groups on Erosion,

Plant Ecology, Public Relations and Roadside Economics. They reported, “The roadsides are but the frame of a continuous panorama landscape and as

such their development must be devoid of artificial effects and replete with natural settings.” The Plant Ecology sub-committee reported, “That

in each region, existing vegetation along a highway furnishes the key to proper selection of the trees and ground cover plants to be established.”

Why did this 1930s understanding of roadsides and the natural environment not continue? This question has no easy answer. It likely involves a combination

of factors: the economy, war, building of the interstate system, increased regulations, and a view of roadsides as extra real estate for further expansion

of infrastructure. Whatever the reasons, more roads meant more development and more disturbance of the environment. Application of ecological principles

to roadsides was not a priority.

In the 1970s, during the energy crunch, some DOTs and land management agencies in need of economic solutions moved away from the traditional agricultural

approach. The needs of public lands were not the same as those of a farm field. Using the local natural plant life found as part of the context of the

project once again made sense. It was during this era that some embraced reduced mowing of roadsides to reduce the use of costly fuels. Using the inexpensive

tool of fire to manage native remnants and native plants reduced costs as well. Preserving remnant native vegetation was preferred, because it was cheaper

and required less energy than seeding newly disturbed soils. Pragmatism shifted practices on the ground. This shift to an ecological approach resulted

in less surface water runoff, increased native seed source, more diversity and improved aesthetics.

In the 21st century, many land managers have fallen back to the reliable and quick solutions that are reminiscent of the agricultural approach. But the

conditions of our economy, the highway’s purpose, and the environment have changed again. We have another energy crunch, an explosion of weed invasions,

and global climate change. We knew an ecological approach held promise in the ’30s. We learned out of necessity in the ’70s that an ecological approach

works. Now we need to adapt our increased knowledge of ecology to current conditions with an eye to the future.

Back to top

PART 1

WHY AN ECOREGIONAL APPROACH?

INTRODUCTION

Community ecology is the study of biotic communities, “A biotic community is composed of all the organisms of all species living in a particular

area.” (Emmel, 1973)

It should not be news that the traditional practices borrowed from agriculture have not succeeded over time. The production goals of farmers and ranchers

differ from environmental stewardship goals of public land managers. Environmental stewardship remains an overall goal of highway design, construction

and management. To minimize impacts and do no harm has been the public mantra since the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). During the1970’s

economic crisis, when fuel costs skyrocketed to $1.25/gal, some State Departments of Transportation looked to the science of ecology for answers.

An ecological approach was discussed coast to coast, but not embraced by all.

Forty years later, while still trying to do the right thing, we are once again stressed by an economic crisis, higher fuel costs, and climate change considerations.

It is time for all land managers to reconsider an ecological approach.

Reference Cited:

Emmel, Thomas C. 1973. An Introduction to Ecology & Population Biology. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. New York.

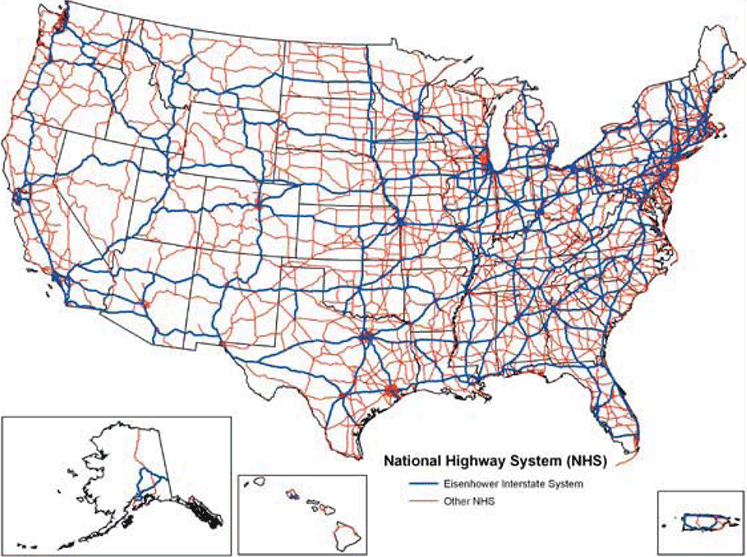

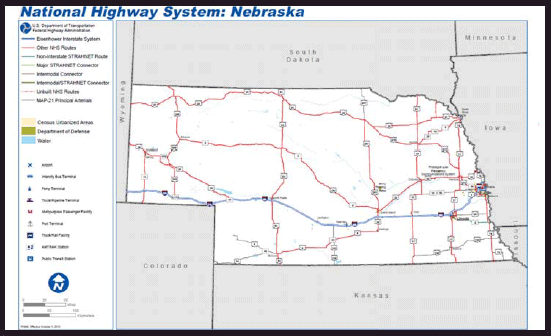

The National Highway System illustrates how highway corridors cross through and potentially impact our biotic communities. As a consequence, shared environmental

stewardship with transportation is key to protecting all lands.

Back to top

CHAPTER 1

ECOLOGY

Ecology is the study of the interrelationships of organisms and their environments, with the stress on interrelationships. One familiar teaching example

is to think of the environment as a giant, stretched-out fish net. If you pull on one part of the net, the entire net will move in response. Just like

that net, the components of our environment, living and not living, are connected. It’s not enough to know what habitats and species exist in the area

you manage. You must know how they relate to one another so that you can successfully manage a roadside habitat.

Why is Ecology Important to Roadside Vegetation Managers?

Humans alter landscapes for our own uses. Historically environmental and ecological impacts were not considered when land use projects were planned. We

have learned that these actions have definite significant impacts, and that it is more cost effective to plan to minimize impacts and ensure that ecological

integrity is retained than to abandon an area and find a new alternative or restore a severely impacted area.

Using an ecological approach to land management is valuable because, plain and simple, it works and saves resources in the long run. In order to properly

manage a roadside habitat and minimize damage so that the ecosystem will continue to function properly, it is critical to understand what makes up the

ecosystem (plant and animal species, soils, water, weather, etc.), how the ecosystem works, what the limiting factors are, and how much impact it will

withstand while still retaining its integrity as a functioning ecosystem.

Understanding Critical Ecological Principles

In 2000, the Land Use Initiative of the Ecological Society of America put together a White Paper entitled “Ecological Principles and Guidelines

for Managing the Use of Land” (ESA 2000). The document identifies five ecological principles or concepts that are important for land managers to

understand so that they can manage an ecosystem for human uses and still retain the integrity of the ecosystem.

The five principles are time, species, place, disturbance, and landscape. For greater detail on the five principles and especially on the guidelines (which

we will only list here) please refer to the original source at Ecological Principles and Guidelines for Managing the Use of Land by V. H. Dale,

S. Brown, R. A. Haeuber, N. T. Hobbs, N. Huntly, R. J. Naiman, W. E. Riebsame, M. G. Turner and T. J. Valone. Ecological Applications Vol. 10, No. 3 (Jun.,

2000), pp. 639-670. Published by: Ecological Society of America. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2641032

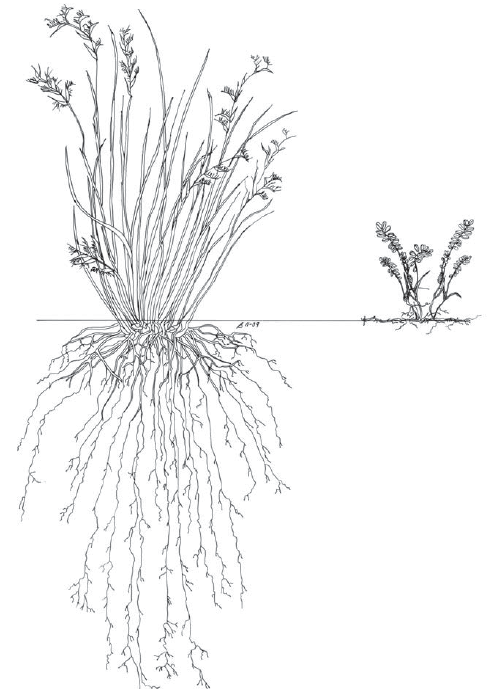

TIME Ecosystems function at many time scales, from the very long (geologic weathering of rock to form soil) to the very short (metabolic

processes within a plant or animal). Ecosystems can change over time, and left alone, the natural pattern of plant succession will take a disturbed roadside

Right-Of-Way (ROW) to a relatively stable plant community which will vary depending on regional conditions.

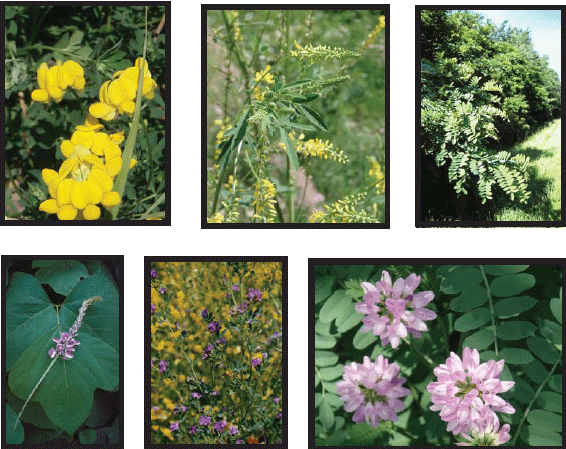

SPECIES It is important to understand the species of plants and animals present in the ecosystem because these species often have complex

interdependencies. A butterfly relies on a plant species to survive. Remove the plant and the butterfly will be gone too. What species are native to the

area and what introduced alien species are threatening the area? Retain and/or restore the native species if at all possible.

PLACE This principle stresses the importance of understanding the unique characteristics of the specific habitat. What are the plant

and animal organisms present, the soil types, water regime, prevailing climate, and geomorphology (slope, orientation, etc.) that characterize the habitat?

Any land management project must consider these specific characteristics because the species that will be established (or maintained) in the habitat must

be able to survive within these constraints.

DISTURBANCE Disturbance of a habitat is the result of natural events, such as wildfires or floods, or human activities, including clearing

native vegetation for agriculture or logging, building transportation systems, or controlling rivers via damming or levees. The type of disturbance will

affect the plant and animal populations that become established after the disturbance.

LANDSCAPE The size, shape, and spatial relationships of the land-cover types (forest edge, grassland, etc.) present will control the

types of plants and animals that can exist in the habitat. Generally larger habitats support a wider range of species and are more stable than smaller

habitats with fewer species. However, small, patchy habitats also can be valuable.

Guidelines for Decision-Making in Land Use Planning

The Land Use Initiative of the ESA used the five ecological principles described above to develop eight land use guidelines to assist managers in planning

roadside vegetation projects. Following these guidelines can help ensure that projects will maintain the integrity of the impacted habitat while still

serving the intended human needs. We will only list the guide lines here and suggest the reader refer to the original source for the specifics of the

guidelines.

- Examine impacts of local decisions in a regional context;

- Plan for long-term change and unexpected events;

- Preserve rare landscape elements and associated species;

- Avoid land uses that deplete natural resources over a broad area;

- Retain large contiguous or connected areas that contain critical habitats;

- Minimize the introduction and spread of nonnative species;

- Avoid or compensate for effects of development on ecological processes; and

- Implement land use and management-practices that are compatible with the natural potential of the area.

Back to top

CHAPTER 2

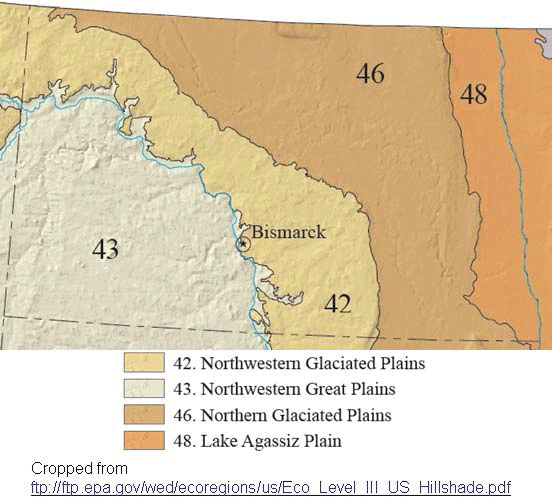

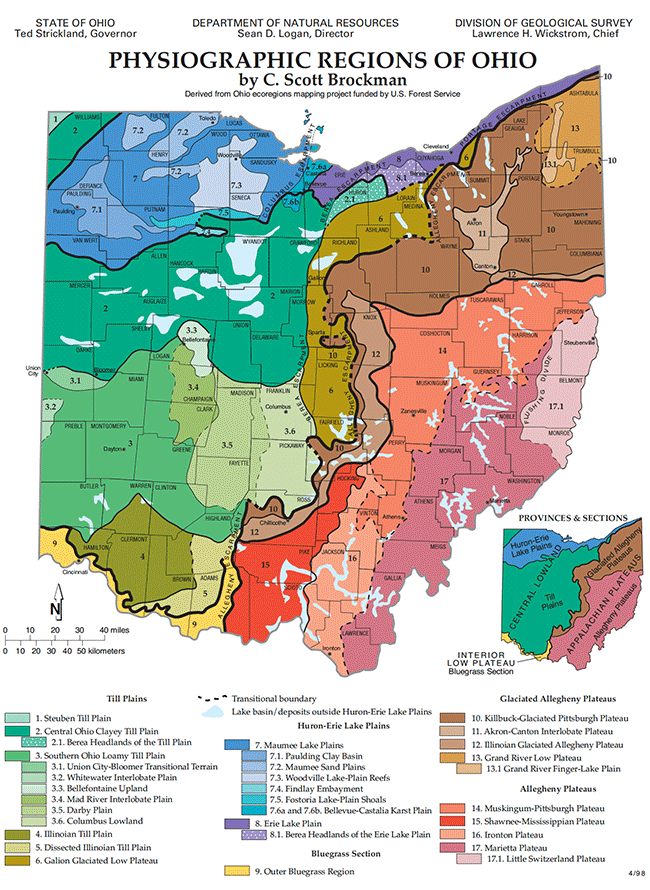

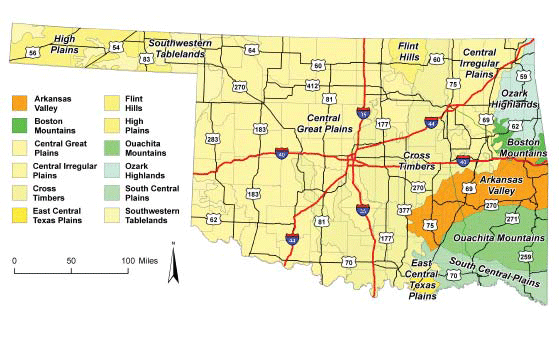

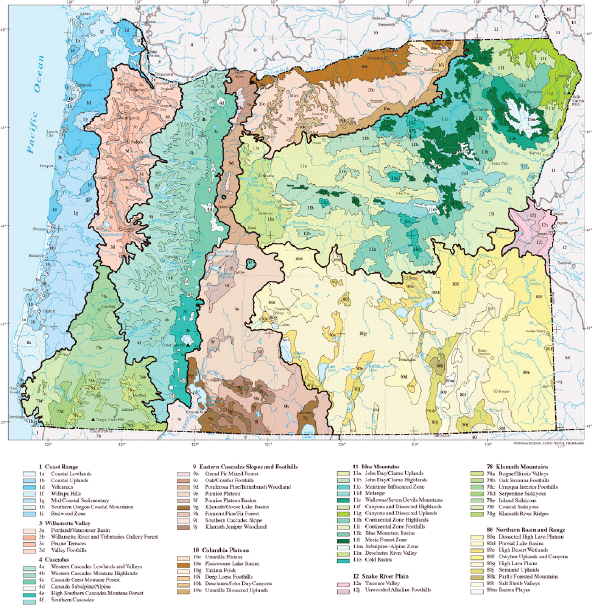

ECOREGIONS

An “Ecoregion” is a conceptual tool used by environmental managers in which landscapes are grouped into units and subunits by their ecologically-relevant

characteristics. The US EPA’s Western Ecology Division (https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions)

describes ecoregions as areas of the landscape that have generally similar characteristics such as landforms, soils, hydrologic resources, and plants

and animals.

How Can an Ecoregional Concept Be Useful to Land Managers?

Ecoregions provide a way for land managers to manage and monitor ecosystems more efficiently. Just as the physical and biological resources within an

ecoregion can be described with some degree of confidence, the responses of that ecoregion to disturbances can be predicted. This aspect of predictability

allows for more efficient management!

Federal Agencies Use Various Ecoregional Approaches

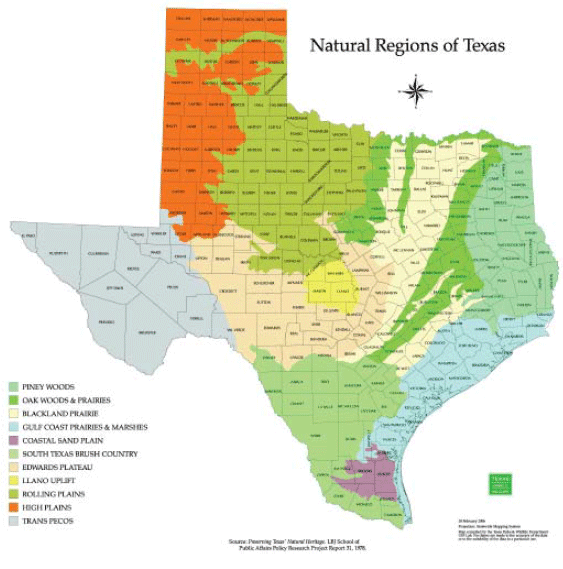

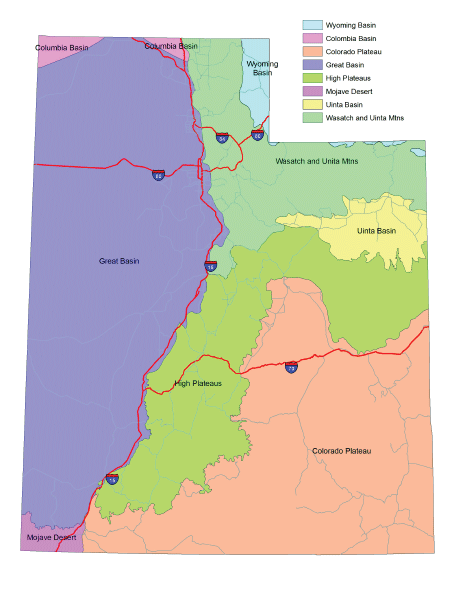

There are several major ecoregional classification systems developed and used by Federal land management agencies in the United States. These classifications

are similar in their basic concepts, but differ in their environmental focus. These ecoregional classification systems, include (1) the U.S. Department

of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Major Land Resource Areas; (2) USDA Forest Service / Robert Bailey Ecoregions; and

(3) USEPA / James Omernik Ecogegions. This handbook- does not recommend any one classification system over another. One system is not “better”

or “preferred” - it’s up to the users to determine which system best fits their needs.

WHAT ARE PLANT COMMUNITIES AND WHY ARE THEY IMPORTANT?

The landscape is more complex than just forests, grasslands, and wetlands. Within any ecosystem, province, or natural region are local assemblages of

species known as plant communities. Collectively, these plant communities are called vegetation. Vegetation differs in kinds of species and total number

of species depending on the local soil and moisture conditions. Although plant communities differ from region to region, they have great similarities

in composition and structure. A mesic prairie in Wisconsin does not differ greatly from a mesic grassland in Kansas, and a lowland forest in West Virginia

is very similar to a lowland forest in Missouri. Understanding plant communities allows us to share solutions to road-side issues across the country.

No State, with the exception of Hawaii, has discreet plant communities.

Continued reaction to change of environment is favorable to some species and unfavorable to others. Drought, soil disturbances, and insect infestations,

will cause the species assemblage to change. In the past, these changes have been predictable. This change over time is known as succession. Succession

is the natural adaptation of plant species to changes.

Back to top

CHAPTER 3

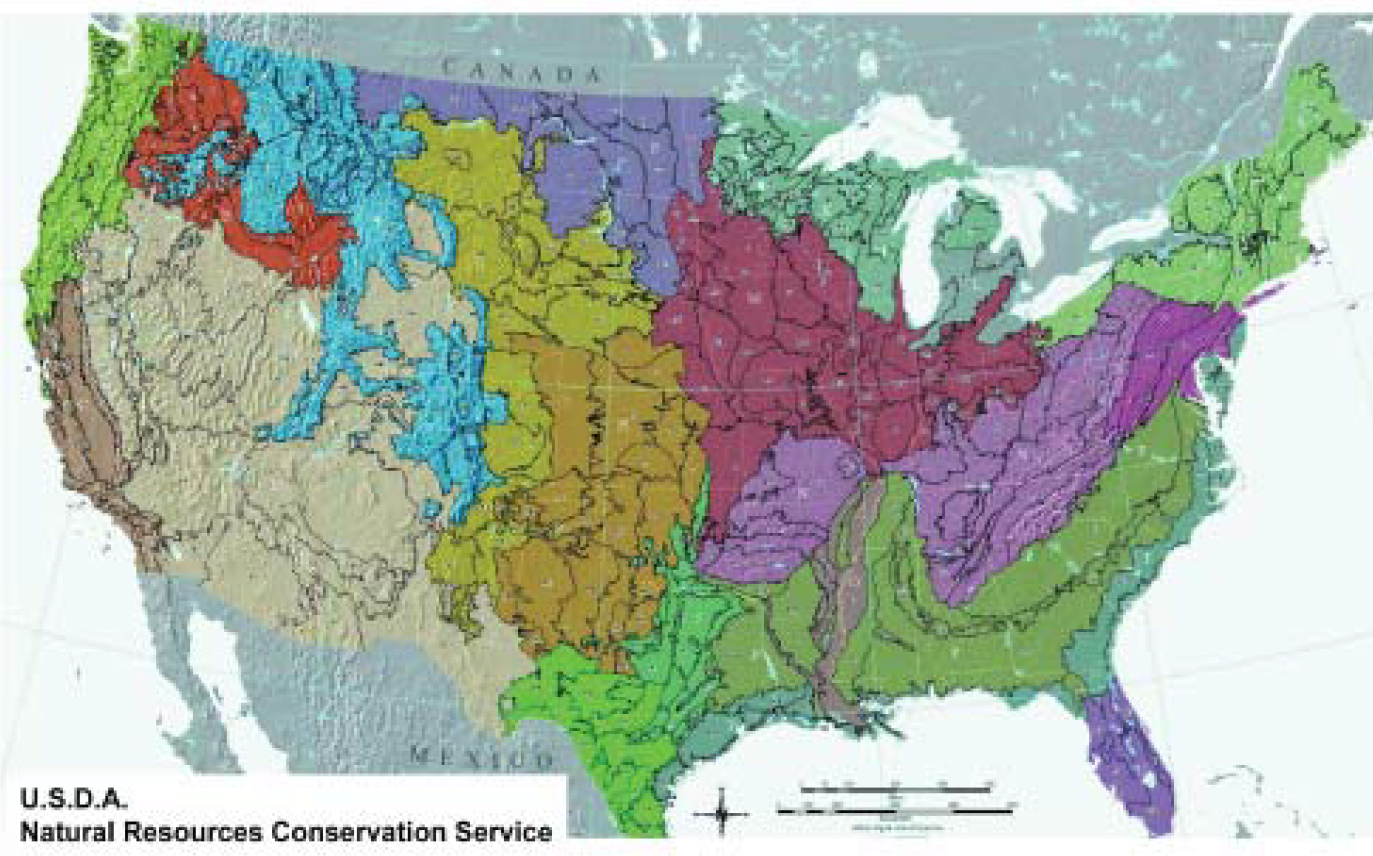

USDA, NRCS Major Land Resource Areas - Soil Focused

One of the earliest ecoregional classification systems is the Major Land Resource Areas (MLRAs), first developed in the early 1970s by the U.S. Department

of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)). This classification system has an agricultural focus

and as a result, the major defining characteristics are soils, climate, water resources, and land use patterns. There are 278 major land resource areas

which are further divided into geographically associated land resource units (LRUs). These LRUs generally correspond to the individual state general soil

map units.

The NRCS uses this system, described in the Agriculture Handbook 296 (USDA 2006), to assist in making national and regional land use decisions, identifying

research and inventory needs, and extrapolating research results across political boundaries. MLRA maps data for the entire United States, the Caribbean,

and the Pacific Basin, are available on the USDA web site at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/

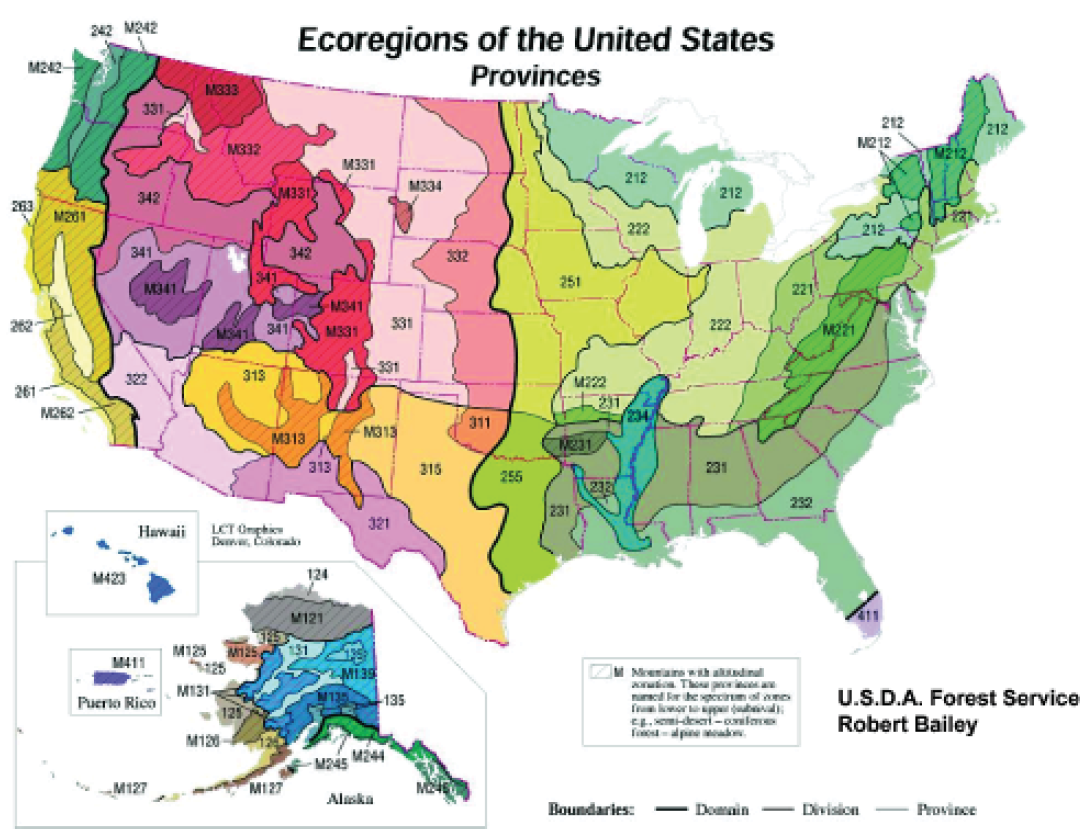

USDA Forest Service / Robert Bailey Ecoregions - Climate Focused

To address the needs of the United States Forest Service, in 1983 Robert Bailey developed an ecoregional classification based on climate, land surface

features (physiography), and potential natural vegetation (based on Kuchler (1964)). There are four levels of detail in Bailey’s ecosystem classification

- Domain, Division, Province, and Section. The geographically largest units are Domains, which are subdivided into Divisions.

Areas within a Division have similar overall climates but are subdivided by precipitation and temperature. Divisions are further subdivided into Provinces,

which are similar in vegetation cover types.

Maps can be downloaded at https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/ecoregions-united-states. -content is no longer available)

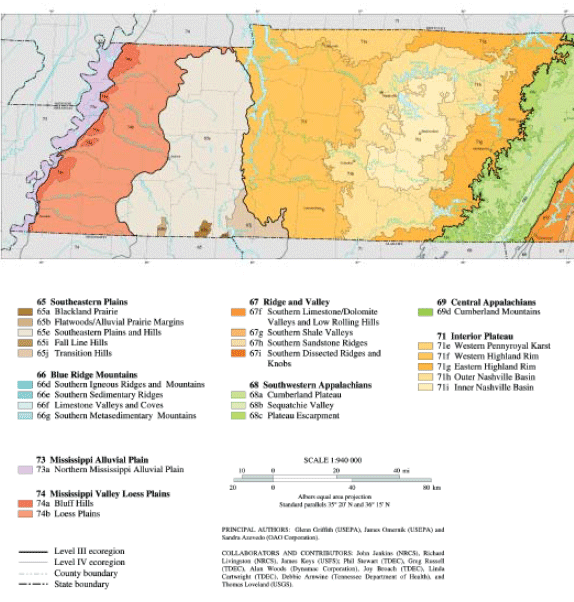

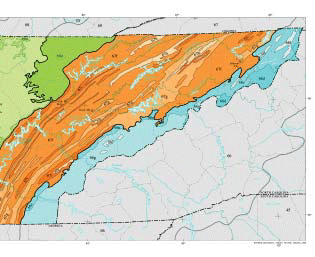

USEPA / James Omernik - Aquatic Ecosystem Focused

James Omernik (1995) describes the earliest attempts in the 1980s by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to classify aquatic resources by adapting

Bailey’s (1976) ecoregional classification system. It is logical that streams in an ecosystem reflect the characteristics of the watershed, that they

drain, and because Bailey’s classification includes many characteristics critical to a watershed, that classification system was a logical starting point.

However, Bailey’s system was not a perfect fit for classifying aquatic ecosystems. EPA developed its own classification system based on their own needs

to classify aquatic ecosystems. The EPA/Omernik classification system is based on the belief that ecoregions are distinct by virtue of spatial variations

of many characteristics, and the predominant characteristics vary from one ecoregion to another. EPA/Omernik’s system gives numbers (Roman numerals),

not names, to the ecosystem levels such that Level I is the most general, Level II is a subdivision of Level I with Level III being the most detailed

level.

After the most general ecosystem classification (Level I) was published in 1987, various States, EPA Regions and Research Labs decided they needed greater detail for their management and research purposes. Cooperative efforts began to develop higher level maps. The Level III map was revised in December 2011 and is available at https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-epa-region. Level

IV maps are being developed and are available at https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-epa-region.

References Cited:

Bailey, R.G. 1983. Delineation of Ecosystem Regions. Environmental Management 7(4):365-373.

Küchler, A.W. 1964. Potential natural vegetation of the conterminous United States. American Geographic Society Special Publication 36. 116 p.

Omernik, J.M. 1987. Map Supplement: Ecoregions of the Conterminous United States. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 77, No. 1 (Mar., 1987), pp.118-125 (article consists of 24 pages).

Omernik, J.M. 1995. Ecoregions: A spatial framework for environmental management. In: Biological Assessment and Criteria: Tools for Water Resource Planning and Decision Making. Davis, W.S. and T.P. Simon (eds.) Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL. pp. 49-62.

USDA. 2006. Major Land Resource Area (MLRA) Land Resource Regions and Major Land Resource Areas of the United States, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Basin. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Handbook 296, Natural Resources Conservation Service(NRSC).

A Practical Application for Seed/Plant Species Choices

The Native Seed Network (NSN) is a program of the Institute for Applied Ecology (http://appliedeco.org/), a non-profit

organization located in Corvallis, Oregon.

The NSN works to provide resources and tools for habitat restoration efforts, and strongly encourages using native plant materials and local-area seed

sources. Their web site has a useful tool for selecting native plant species and seed sources based on the ecoregion where the project is located. The

NSN web site also offers an ecoregion map, based on the USEPA / Omernik ecosystem, which allows a site visitor to click on his or her State and retrieve

a native plant list by city or the specific subregion. Native plant information is from the PLANTS database of the NRCS at

http://plants.usda.gov/.

This type of application can be highly valuable to a land manager who may not have a strong background in ecology or botany but has to plan a revegetation

of habitat restoration project. The user can go to one web site and be directed to the proper ecoregion and subregion and then get a plant list specifically

for that subregion.

Back to top

PART 2

STATE ECOREGION MAPS, MODELS, AND RESOURCES

Introduction

HOW TO USE AN ECOREGION MAP FOR DECISION-MAKING

Transportation professionals have talked about an “Ecological Approach to Roadside Planting”, since 1941, when G.B. Gordon described it at

the legendary annual Ohio Short Course. This event took place annually from 1941-1966 and examined roadside development issues. Weed Control by Chemical

Treatment was discussed in 1946. Grasses, An Economical Approach to Erosion Control was described in 1953.

Half a century later, we continue to look for ecological and economical answers. This book includes “how-tos” for many of the land management

issues we continue to have in common. It also includes an ecoregion map for each State’s reference. Here are suggested steps for using the resources included

in Part 2 for your specific State:

- Look at your State’s map to get the lay of the land or big picture.

- Identify the natural region or ecological landscape in which your project is in located.

- Contact your State’s Natural Heritage Program (also shown) to find a preserve or natural example typical of that region.

- Visit the preserve or natural area to better understand the plant communities and species that are common there. Observe how they are structured and where

plants grow best. What grows in the wet areas that match your ditches? What grows in the driest parts that match slopes?

- Ask the Natural Heritage Program for a plant inventory list of the preserve to get correct common and scientific names to avoid mistakes in specifications

later. This natural area becomes your model or reference site for the plantings you do. It will allow you a benchmark for comparison over time to learn

what worked and what did not.

EXAMPLE:

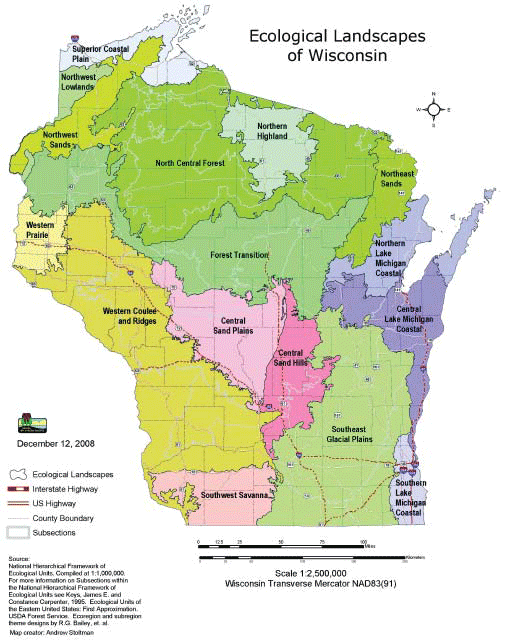

A project is just north of LaCrosse, Wisconsin. Look at the map on page 122 to find the surrounding natural region is called the “Western Coulee

and Ridges”. Call the listed contact and ask for a location to visit and also ask for a plant inventory list for note making on site visit.

VISIT A PRESERVE

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants

of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically

important lands and waters for nature and people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project. To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google

Earth (example below), you can use their feed url http://my.nature.org/preserves/.

Back to top

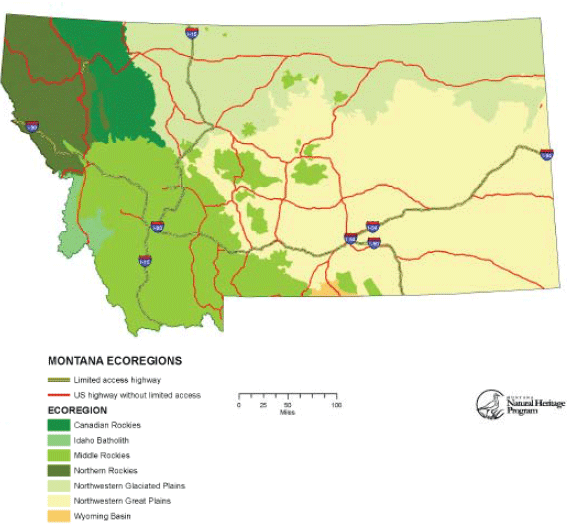

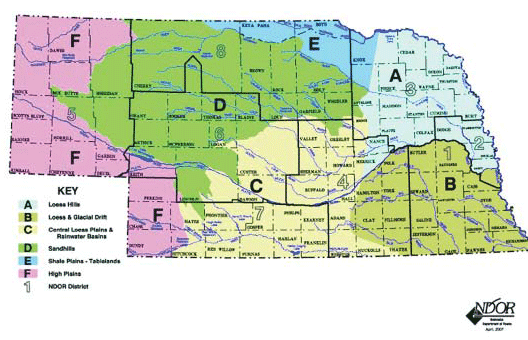

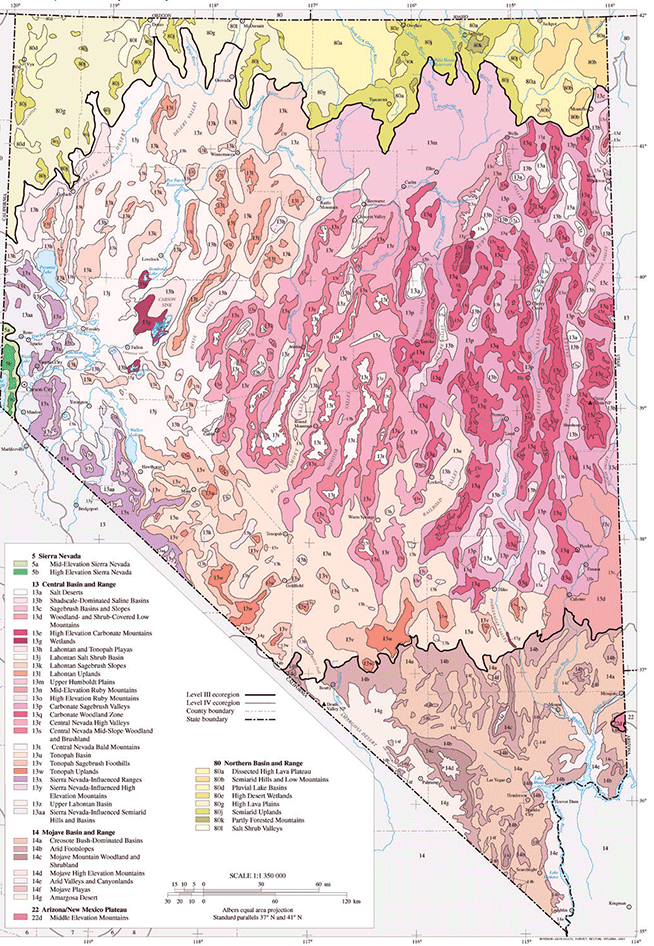

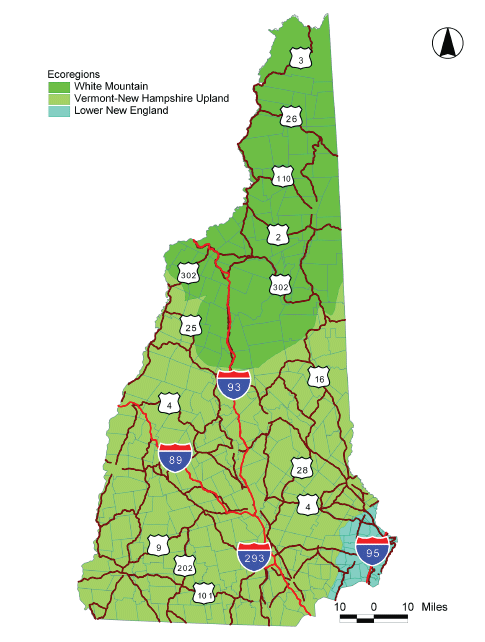

50 STATE ECOREGION MAPS, MODELS, AND RESOURCES

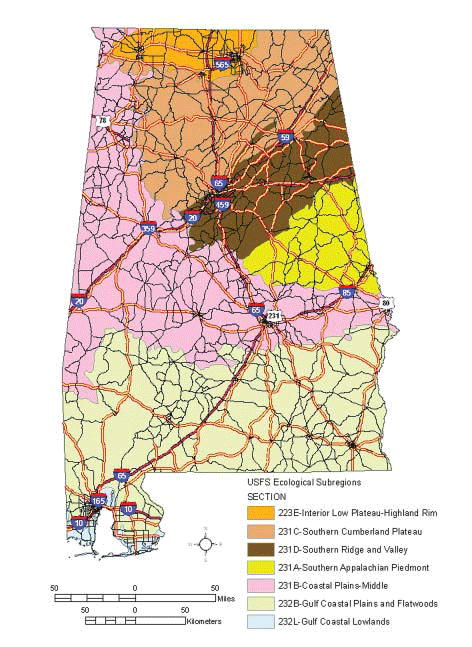

ALABAMA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Alabama has seven ecoregions which follow the designations by Bailey and the US Forest Service. These ecoregions include: Interior Low Plateau-Highland

Rim; Southern Appalachian Piedmont; Coastal Plains-Middle; Southern Cumberland Plateau; Southern Ridge and Valley; Gulf Coastal Plains and Flatwoods;

and Gulf Coastal Lowlands.

SOURCES:

Cleland, DT., J. A. Freeouf, J. E. Keys Jr., G. J. Nowacki, C. Carpenter, W.H. McNab. 2007. Ecological subregions: sections and subsections of the conterminous

United States [1:3,500,000].

Sloan, A.M., cartog. Gen. Tech. Report WO-76.Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Map creator: Michael Barbour, GIS Analyst,

AL NHP, Auburn University, AL.

NHP CONTACT:

Alabama Natural Heritage Program 1090 South Donahue Drive Auburn University, AL 36849 Phone: 334-844-5019 Fax: 334-844-4462

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

An example of the Black Belt Prairie, a mosaic of natural grassland and hardwood forest and well represented throughout the Coastal Plain of west central

Alabama, is located along either side of County Road 9, roughly 0.1 road miles north of County Road 2, approximately 9.0 air miles southwest of downtown

Selma.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

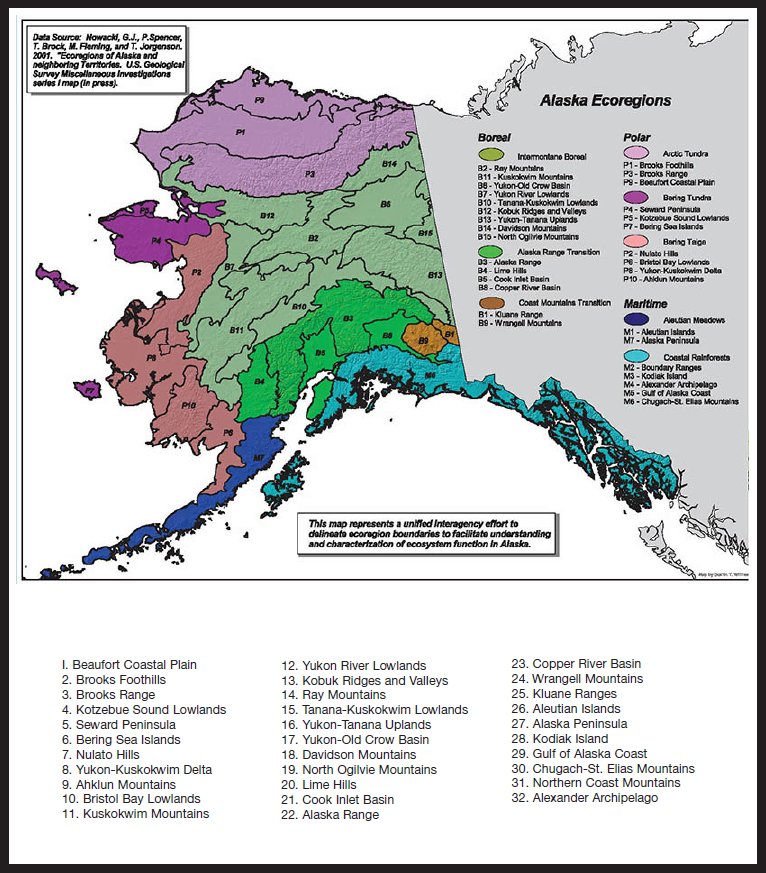

ALASKA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

The Unified Ecoregions Map of Alaska combines the Bailey/US Forest Service and Omernik approaches. The ecoregions are described in detail (and shown in

greater clarity than can be provided here) at http://forestry.alaska.gov/pdfs/00ecoregions.pdf

SOURCES:

Nowacki, G.J.; P.Spencer; T.Brock; M.Fleming; and T.Jorgenson. 2001. Ecoregions of Alaska and Neighboring Territories. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous

Investigations series I map (in press).

NHP CONTACT:

Program Manager/Program Ecologist Alaska Natural Heritage Program University of Alaska-Anchorage 707 A Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-257-2783

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

Calamagrostis canadensis (bluejoint) dominates the Bluejoint Grasslands, which is one of the most common and widespread grassland associations

in southeast and south central Alaska. Road accessible examples of this association occur along Hatcher Pass Road north of Palmer near Independence Mine State

Historical Park, and Turn Again Pass south of Anchorage along Highway 1.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

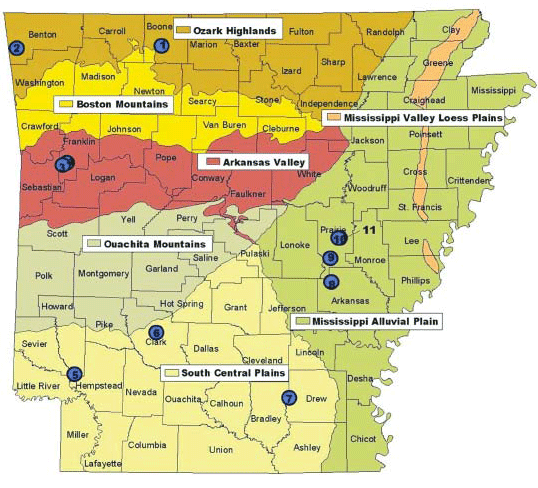

ARKANSAS ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Arkansas has seven Level III ecoregions which follow the designations by Omernik. These ecoregions include Ozark Highlands; Boston Mountains; Arkansas

Valley; Ouachita Mountains; South Central Plains; Mississippi Alluvial Plain; and Mississippi Valley Loess Plains. Descriptions are available at

http://www.wildlifearkansas.com/ecoregions.html.

SOURCE:

Woods A.J., Foti, T.L. , Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M., Wise, J.A., Murray, E.O., Prior, W.L., Pagan, J.B., Jr., Comstock, J.A., and Radford, M., 2004,

Ecoregions of Arkansas (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs). Reston, Virginia, U.S. Geological Survey (map

scale 1:1,000,000).

CONTACTS:

Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission 1500 Tower Building, 323 Center Street Little Rock, Arkansas 72201 Data Manager/Environmental Review Coordinator,

Phone: 501-324-9762

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

Grasslands in Arkansas’s ecoregions are listed below along with the Counties in which they are found and the map number associated with the grassland.

Descriptions and precise locations are available at http://www.naturalheritage.com/areas/map.asp.

OZARK HIGHLANDS

Baker Prairie Natural Area, Boone Co. Map # 1

Chesney Prairie Natural Area, Benton Co. Map # 2

ARKANSAS VALLEY

Cherokee Prairie Natural Area, Franklin Co. Map # 3

H. E. Flanagan Prairie Natural Area, Franklin Co. Map # 4

Saratoga Blackland Prairie Natural Area, Howard Co. Map # 5

SOUTH CENTRAL PLAINS:

Terre Noire Natural Area, Clark Co. Map # 6

Warren Prairie Natural Area, Bradley & Drew Cos. Map # 7

MISSISSIPPI ALLUVIAL PLAIN:

Roth Prairie Natural Area, Arkansas Co. Map # 8

Konecny Prairie Natural Area, Prairie Co. Map # 9

Railroad Prairie Natural Area, Prairie & Lonoke Cos. Map # 10

Downs Prairie Natural Area, Prairie Co. Map # 11

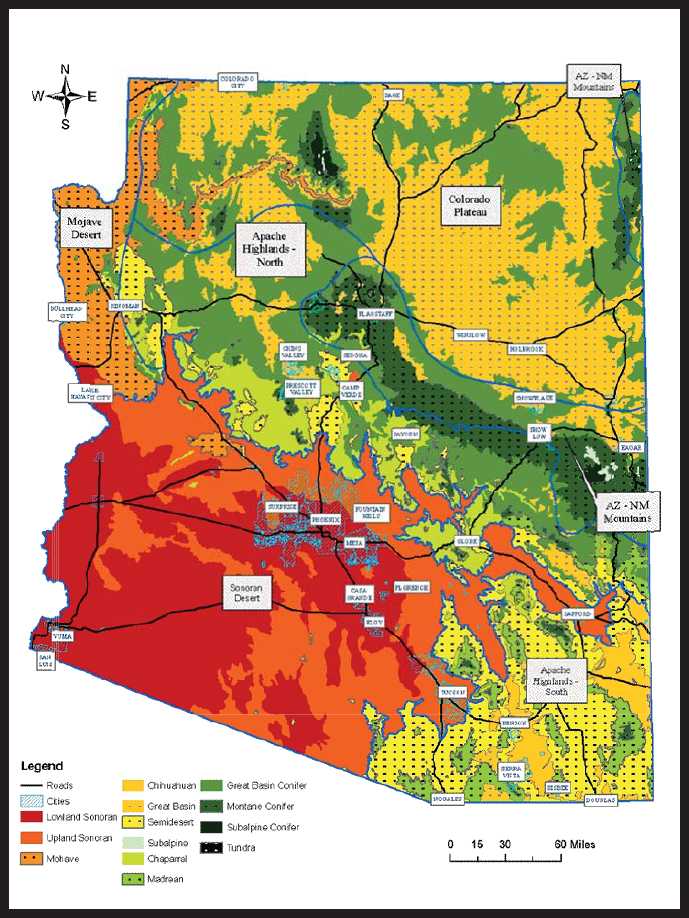

ARIZONA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Under Arizona’s Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) six ecoregions are described following the designations of Omernik. These ecoregions

include: Colorado Plateau, Arizona-New Mexico Mountains, Apache Highlands North, Apache Highlands South, Sonoran Desert, and Mohave Desert.

SOURCE:

Arizona’s Natural Heritage Program(HDMS) https://www.azgfd.com/

CONTACT:

Arizona Game & Fish Department

WMHB - Project Evaluation Program

5000 W. Carefree Hwy

Phoenix, AZ 85086-5000

HDMS Program Coordinator

Phone: 623-236-7618

Fax: 623-236-7366

Additional contacts are listed at https://www.azgfd.com/.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

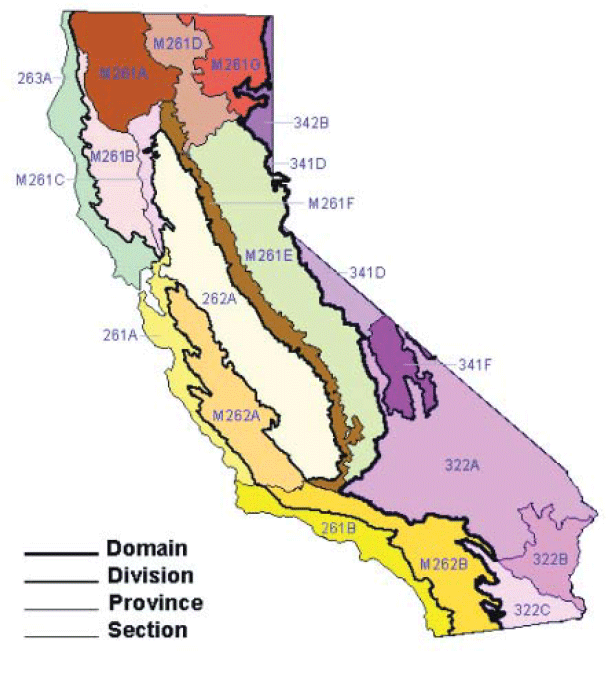

CALIFORNIA ECOREGIONS

261A: Central California Coast

261B: Southern California Coast

262A: Great Valley

263A: Northern California Coast

M261A: Klamath Mountains

M261B: Northern California Coast Ranges

M261C: Northern California Interior Coast Ranges

M261D: Southern Cascades

M261E: Sierra Nevada

M261F: Sierra Nevada Foothills

M261G: Modoc Plateau

M262A: Central California Coast Ranges

M262B: Southern California Mountains and Valleys

322A: Mojave Desert

322B: Sonoran Desert

322C: Colorado Desert

341D: Mono

341F: Southeastern Great Basin

342B: Northwestern Basin and Range

ECOREGIONS:

California has 19 ecological sections that follow the designations by Robert Bailey and the USDA, Forest Service. More information at http://www.dot.ca.gov/design/lap/.

SOURCE:

USDA, Forest Service https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/ecoregions-united-states.

CONTACT:

Biogeographic Data Branch of the Calif.

Dept. of Fish and Game

1807 13th Street, Suite 202,

Sacramento, CA 95811

Phone: 916-322-2493

Fax: 916-324-0475

Web site: https://wildlife.ca.gov/Organization/BDB

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

The five major grassland types in California, recognized by many ecologists, are:

- COLD DESERT GRASSLANDS- NE part of Southern Cascades, Modoc Plateau, Northwestern Basin and Range, and Mono ecological sections.

- NORTH COASTAL GRASSLANDS- Northern to Central Calif. Coast ecological sections.

- SERPENTINEGRASSLANDS- on serpentine outcrops, similar to Valley grasslands.

- VALLEY/SOUTH COASTAL GRASSLANDS(also called Valley needle grass grassland, California prairie, or California annual grassland) found in the Great

Valley eco-logical section.

- WARM DESERT GRASSLANDS, found in Colorado, Southeastern Great Basin ecological sections.

References:

Todd Keeler-Wolf, Julie M. Evens, Ayzi K I. Solomeshch, V. L. Holland, And Michael G. Barbour. Chp. 3 Community Classification and Nomenclature

in Stromberg, M.R., J.D.Corbin, C.M. D’Antonio, Editors. 2007. California Grasslands: Ecology and Management. The Regents of the Univ. of Calif., Los

Angeles.http://www.cnps.org/cnps/vegetation/pdf/grassland_stromberg07_ch3.pdf

SITES TO VISIT:

GREAT VALLEY GRASSLANDS STATE PARK, San Joaquin Valley, remnant stands of Sporobolus airoides (native bunchgrass).

http://www.parks.ca.gov/.

TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, Wildcat Canyon near Berkeley has a coastal grassland site with native grasses, on Nimitz Way.

http://www.ebparks.org/parks/tilden.htm.

BEAR CREEK BOTANICAL MANAGEMENT AREA (BMA), 20 miles west of Williams along Highway 20 in western Colusa County. The BMA is a remnant of Inner Coast Range

vegetation. 20 BMAs are part of a Caltrans program that identifies, preserves and manages significant native plant communities along roadsides.

The California Native Grasslands Association has a "Guide to Visiting California’s Grasslands" at http://www.cnga.org/visitor_guide.html.

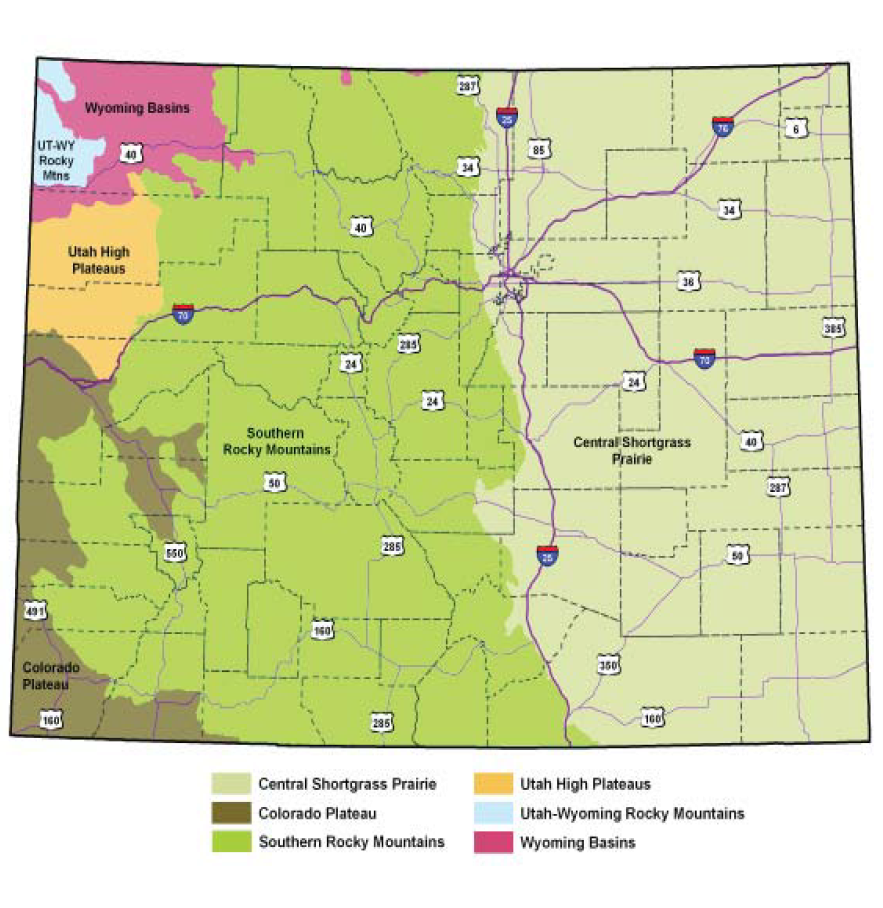

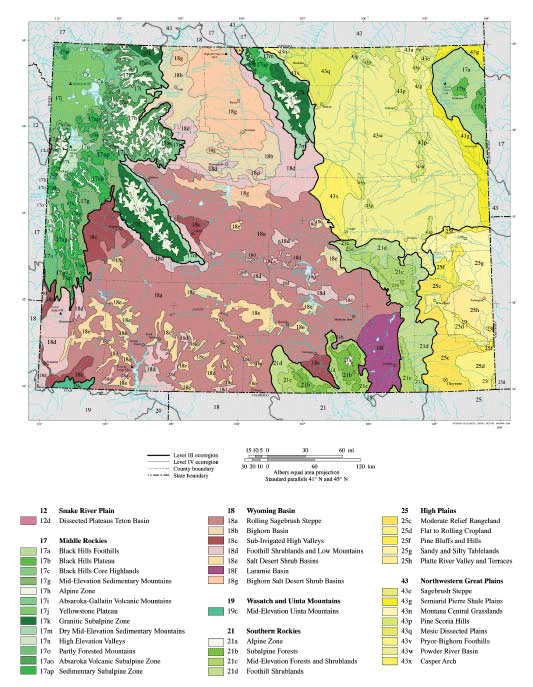

COLORADO ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Colorado contains parts of six ecoregions as delineated by The Nature Conservancy (modified from Bailey 1995,

https://www.fs.usda.gov/rmrs/ecoregions-united-states/). East of the mountain front the State is part of the Central Shortgrass Prairie. The mountainous

central portion of the State forms the bulk of the Southern Rocky Mountains ecoregion. On the western edge of the State, four ecoregions are shared with

neighboring States: Wyoming Basins, Utah-Wyoming Rocky Mountains, Utah High Plateaus, and the Colorado Plateau.

SOURCE:

Colorado Natural Heritage Program to http://www.cnhp.colostate.edu/.

NHP CONTACT:

Environmental Review Coordinator Colorado Natural Heritage Program

Colorado State University

8002 Campus Delivery

Fort Collins, CO 80523-8002

Phone: 970-491-7331

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

Grasslands in Colorado are greatly influenced by elevation and local climate. On the eastern plains, Shortgrass Prairie is typical. With increasing elevation

and precipitation at the transition between plains and mountains, Foothills-Piedmont Grassland types appear. In the higher, wetter elevations of the Southern

Rocky Mountains, a variety of Montane Grasslands and Subalpine Grasslands are found. Sparse Semi-desert Grassland communities are typical of the drier,

warmer mesas and canyons of the western slope. Maps of natural areas, including grassland examples, in Colorado are available at

https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5389835.html.

The U.S.D.A. Forest Service manages the following National Grasslands in Colorado. Information and links located at

https://www.fs.usda.gov/recmain/arp/recreation.

- Comanche National Grassland is located in southeastern Colorado in two areas: south of Springfield and southwest of La Junta.

- Pawnee National Grassland located in north central Colorado east of Ft. Collins in an area bounded by Routes 85, 14 and 71.

- Gila National forest, 9,075 acres.

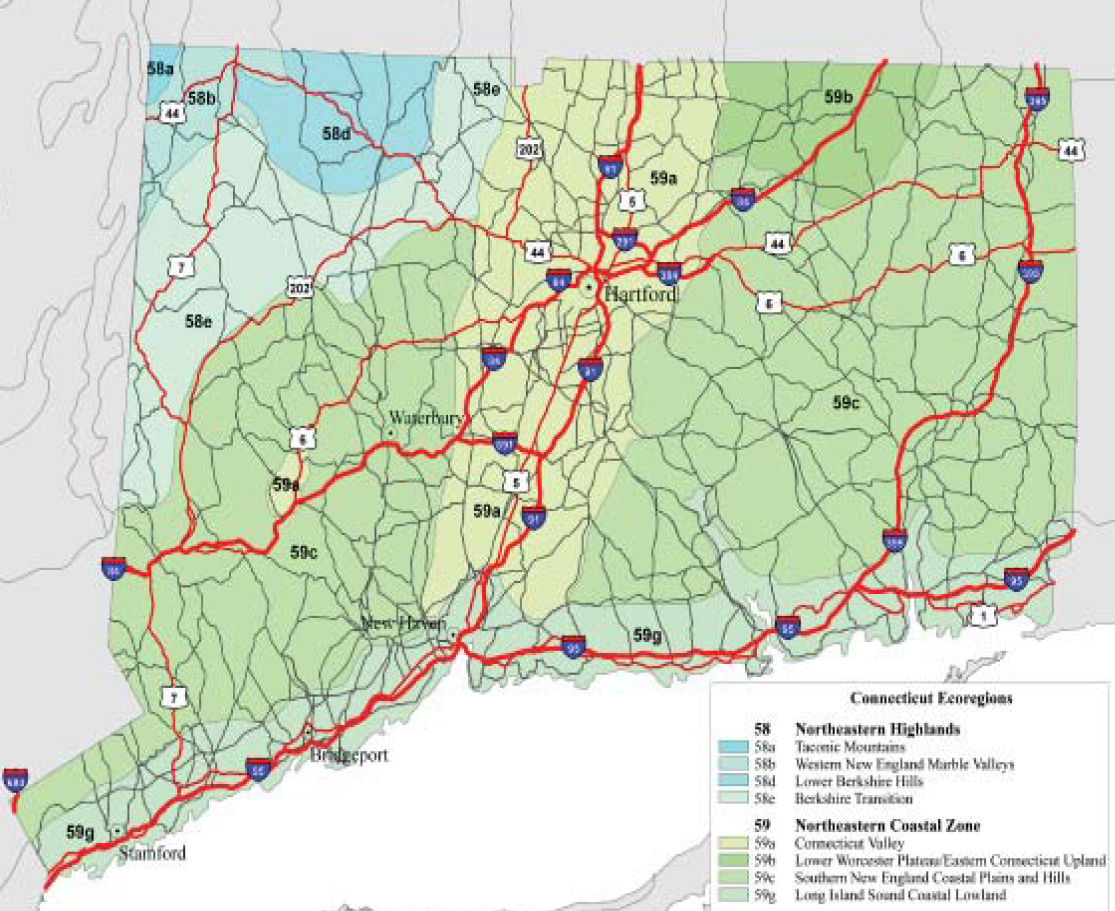

CONNECTICUT ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Connecticut has two Level III ecoregions following the designations by Omernik. These ecoregions are Northeastern Highlands and Northeastern Coastal Zone,

which are further subdivided into four Level IV ecoregions each. These ecoregions are shown on the attached map and described at

https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-continental-united-states.

SOURCE:

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Western Ecology Division, Corvallis, Oregon https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-continental-united-states.

BNR CONTACT:

Connecticut Natural Diversity Database Bureau of Natural Resources, Wildlife Division

Department of Environmental Protection

79 Elm Street, Sixth Floor

Hartford, CT 06106-5127

Phone: 860-424-3540

Fax: 860-424-4058

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

Connecticut’s Department of Environmental Protection has produced a guideline entitled “Managing Grasslands, Shrublands, and Young Forest Habitats”

which provides useful information on managing grasslands. The document can be obtained from the DEP Online Store http://www.ct.gov/dep/cwp,

79 Elm St

Hartford, CT 06106-5127

Phone: 860-424-3555, Fax: 860-424-4088.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url -

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

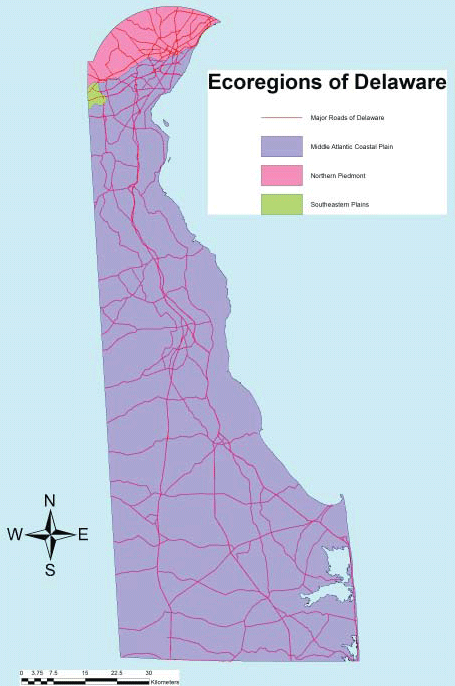

DELAWARE ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Delaware has three Level III ecoregions, including: Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain, Northern Piedmont, and Southeastern Plains.

SOURCE:

Ecoregion map was drawn by Robert Coxe based on EPA Level III maps following Omernick’ designations. Roads data are from Delaware Department of Transportation.

NHP CONTACT:

Delaware Natural Heritage Program Division of Fish & Wildlife

Dept. of Natural Resources & Environ. Control

89 Kings Highway,

Dover, DE 19901

Phone: 302-653-2880

Fax: 302-653-3431

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

A suitable example is located on DE Route 273 and I-95 Roadside, on the roadside of the southbound DE 273 onramp to I-95. This 5 acre area is managed

with different levels of mowing: regularly mowed roadside strip, yearly mowed zone, shrub zone mowed once every five years and unmowed area. Prior to

1998, this entire area was mowed to a tree line. It has been allowed to grow since then and a grassland, forb, shrub and tree community has developed.

Most of the area is dry, but a drainage ditch through the center provides a moist zone. The unmowed zones are spot sprayed to reduce incursion of invasive

species. Species include switch grass (Panicum virgatum), little bluestem (Schizacharium scoparium), rugose goldenrod (Solidago rugosa),

hyssop-leaf thoroughwort (Eupatorium hyssopifolium), three-nerved joe-pye weed (Eupatorium dubium), sweet pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia),

highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), arrow-wood (Viburnum dentatum), sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua), red maple (Acer

rubrum) and many more.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

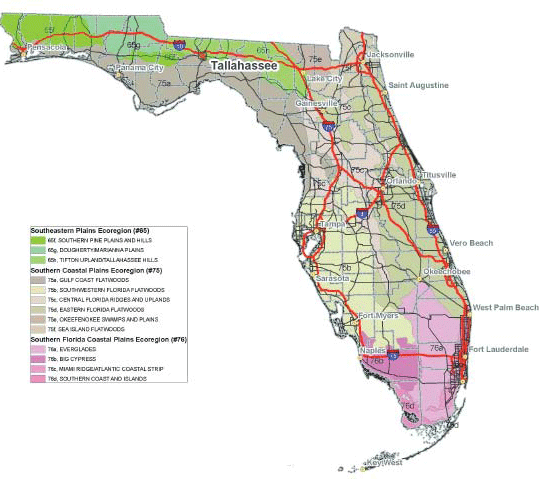

FLORIDA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Florida has three Level III ecoregions: (65) Southeastern Plains, (75) Southern Coastal Plain, and (76) Southern Florida Coastal Plain. Descriptions of

these ecoregions are found at US EPA’s Western Ecology Division web site at https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions

SOURCE:

Florida Department of Transportation,

Environmental Management Office,

605 Suwannee St MS 37

Tallahassee, FL 32399

Phone: 850-414-4447.

FNAI CONTACT:

Florida Natural Areas Inventory

1018 Thomasville Road, Suite 200-C

Tallahassee, FL 32303

Phone: 850-224-8207

Web >site: http://www.fnai.org/

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

MESIC FLATWOODS are flatland with sand substrate; mesic; subtropical or temperate; frequent fire; slash pine and/or longleaf pine with saw palmetto,

gallberry and/or wiregrass or cutthroat grass understory. Although forested, this natural community is basically grassland with a thin, open-canopy

of pines. Reference site: Apalachicola National Forest, 30 05 34.4 N, 85 02 28.8 W.

SANDHILL are upland with deep sand substrate; xeric; temperate; frequent fire (2-5 years); longleaf pine and/or turkey oak with wiregrass understory;

also a lightly forested natural community with a grassy understory. Reference site: Ocala National Forest, 29 27 16.6 N, 81 48 32.7 W.

DRY PRAIRIE are flatland with sand substrate; mesic-xeric; subtropical or temperate; annual or frequent fire; wiregrass, saw palmetto, and mixed grasses

and herbs; as much a shrubland as grassland. Reference site: Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park, 27 34 52.1 N, 81 01 59.4 W.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

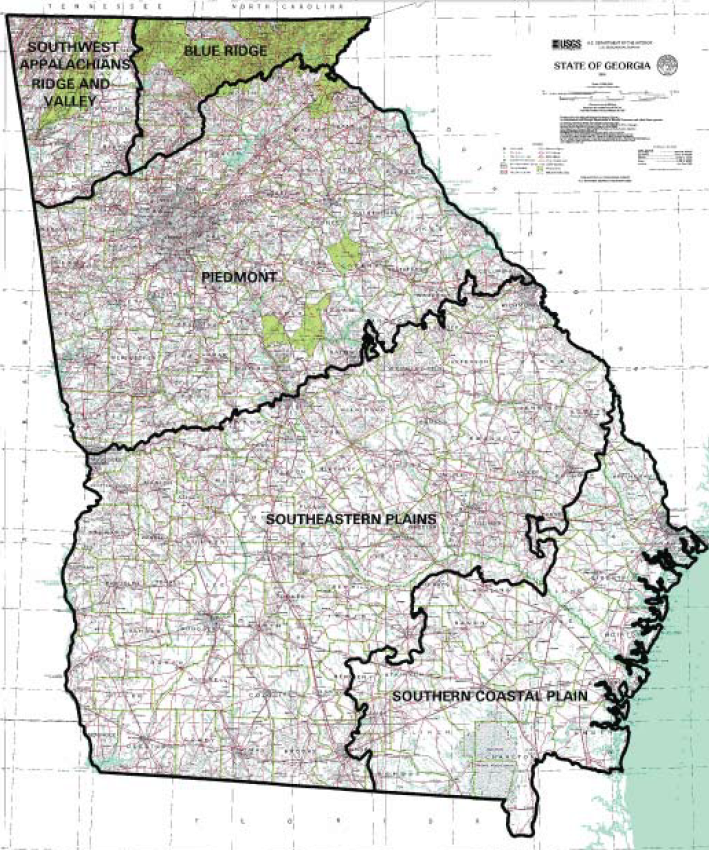

GEORGIA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Georgia has five Level III ecoregions, including: Southwest Appalachians Ridge and Valley, Blue Ridge, Piedmont, Southeastern Plains, and Southern Coastal

Plains.

SOURCE:

Map was downloaded in November 2008 from the Georgia GIS Data Clearinghouse https://gis1.state.ga.us/index.asp

by Chris Canalos, Georgia DNR. Original data from: Griffith, G.E., J.M. Omernik, J.A. Comstock, S. Lawrence, G. Martin, A. Goddard, V.J. Hulcher, and

T. Fulcher. 2001. Ecoregions of Alabama and Georgia.

U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA; and U.S. Geological Survey. 2001. State of Georgia topographic map (DRG), 1:500,000. Reston, VA, U.S. Geological Survey.

DNR CONTACT:

Georgia Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Nongame Conservation Section 2065 US Hwy 278, SE

Social Circle, GA 30025

Phone: 770-918-6411 or 706-557-3032

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

Red Top Mountain State Park in Bartow County northwest of Atlanta on Rt. 75, has some narrow strips of native grasses by the sides of Red Top Mountain

Road which runs through the park. The coordinates for the location are N 34.13989755, W -84.69890775 (WGS84); or UTM 17: 3783852.30000194, 158886.53988348.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

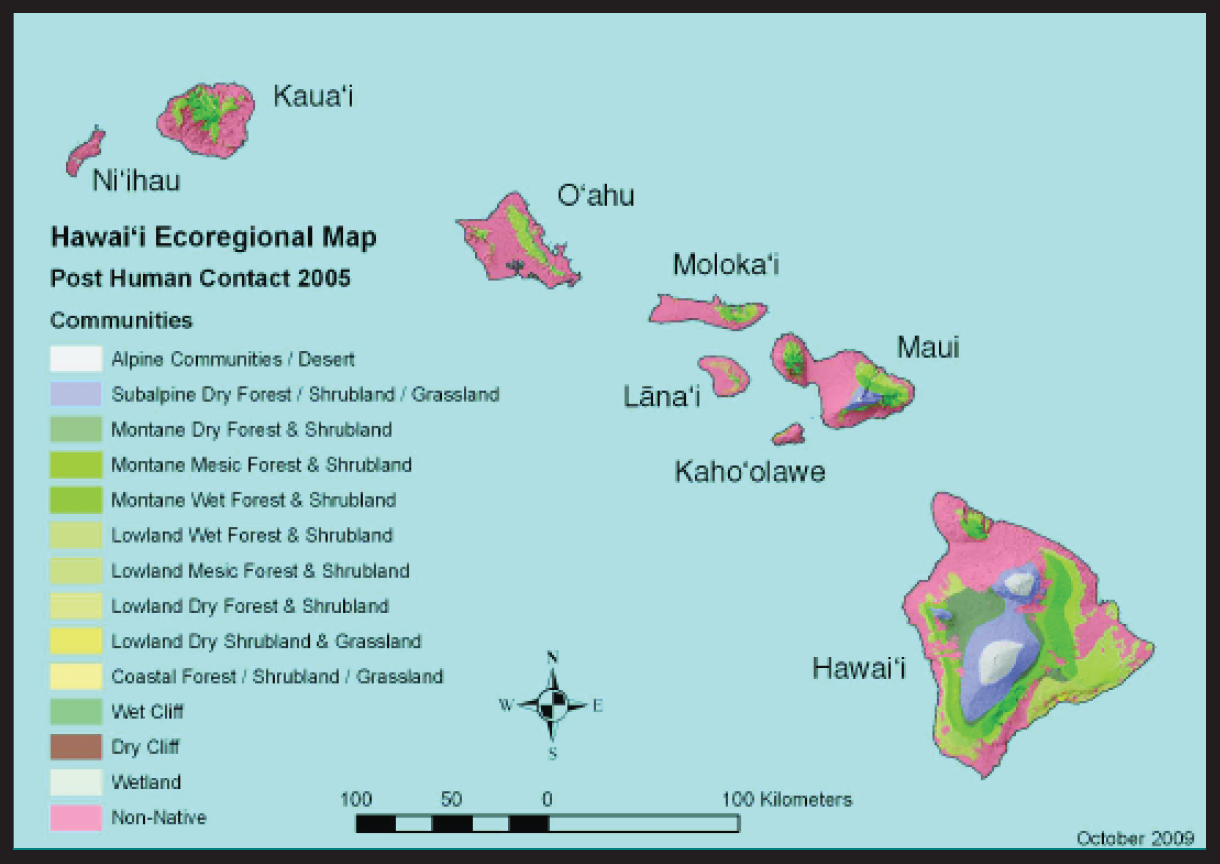

HAWAII ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Three ecoregion categories (Alpine, Subalpine and Coastal) are grouped according to elevation, moisture, and physiognomy, following the natural community

classification currently in use by The Nature Conservancy of Hawaii see http://www.hawaiiecoregionplan.info/introduction.

html. For more information see the Atlas of Hawaii, Chapter “Terrestrial Ecosystems”. Fourteen communities, including nonnative vegetation,

are shown in the attached map.

SOURCE:

Hawaii Biodiversity & Mapping Program Juvik, S.P., J.O. Juvik, and T.R. Paradise. 1998. Atlas of Hawaii Third Edition. University of Hawaii

Press. ISBN-10 0824821254.

CONTACT:

Hawaii Biodiversity & Mapping Program

University of Hawaii at Manoa Center for Conservation Research & Training

3050 Maile Way, Gilmore Hall 406

Honolulu, HI 96822

Phone: 808-956-8094

Fax: 808-956-8493

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

The vegetation of Hawaii is unique for many reasons and there are few remaining native grasslands. The Nature Conservancy’s Mo’omomi Preserve has good

examples of coastal area grassland with ’aki’aki (Sporobolus virginicus) with mixed native coastal subshrubs. In the NW Hawaiian Islands, there

are kawelu (Eragrostis variabilis) grasslands, also with native coastal shrubs. Examples of high elevation native grasslands include subalpine

East Maui, dominated by Deschampsia spp., and the Mauna Kea grasslands which are dominated by Hawaiian bentgrass (Agrostis sandwicensis),

and pili uka (Trisetum glomeratum).

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

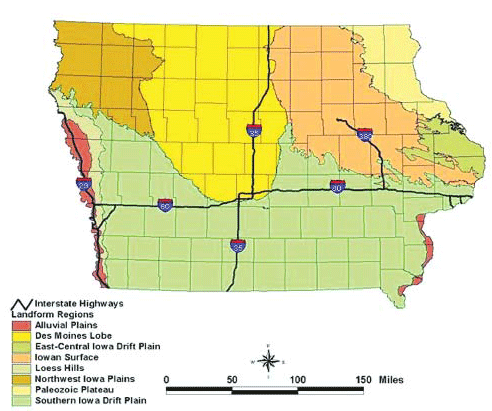

IOWA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Iowa has eight landforms regions, including: Alluval Plains, Des Moines Lobe, EastCentral Iowa Drift Plain, Iowan Surface, Loess Hills, Northwest Iowa

Plains, Palezoic Plateau, and Southern Iowa Drift Plain. Descriptions of the landform regions and historic plant communities in each region are available

at http://www.iowadnr.gov/.

SOURCE:

Iowa Department of Natural Resources http://www.iowadnr.gov/

DNR CONTACT:

Plant Ecologist

Department of Natural Resources

Wallace State Office Building

502 East 9th Street

Des Moines, IA 50319-0034

Phone: 515-281-3891

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

The Hayden Prairie, a 242-acre native prairie, is located in Howard County, 4.9 miles west of Lime Springs on A23 at the Intersection of Jade Avenue and

50th Street. Information and map at

http://www.iowadnr.gov/.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

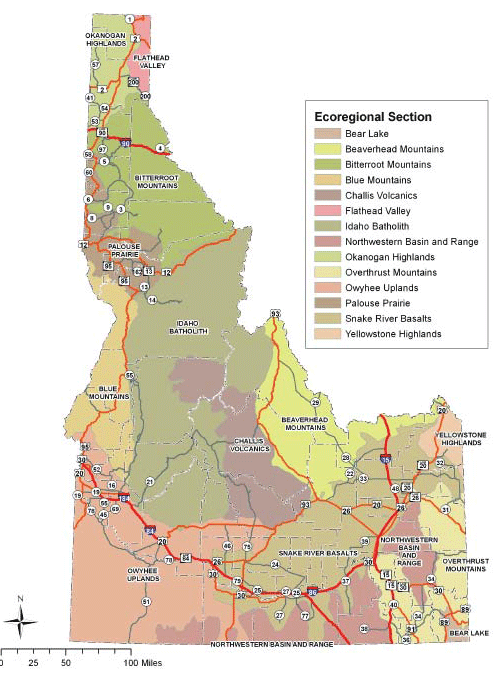

IDAHO ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Idaho encompasses 14 sections of four Level III ecoregions following the Omernik designations. There are 5 major grassland ecological systems in the State.

The extent of these 5 grassland ecological systems, the ecoregion in which they are found, and the common grassland species found in each are listed under

“Grassland Examples”.

SOURCE:

https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-continental-united-states

CONTACT:

Habitat andRestoration Ecologist Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Wildlife Bureau, Habitat Section

600 S. Walnut St., P.O. Box 25

Boise, ID 83707

Phone: 208-287-2728

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

CANYON GRASSLANDS are found in the Blue Mountains and Idaho Batholith ecoregions; species present include: red threeawn (Aristida purpurea var. longiseta);

Idaho fescue (Festuca idahoensis); needle and thread (Hesperostipa comata); Sandberg’s bluegrass (Poa secunda); bluebunch wheatgrass

(Pseudoroegneria spicata); sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus).

THE CECIL D. ANDRUS WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA, one of the best places to view canyon grassland communities, is located in Washington County about 18 miles

northwest of Cambridge along Highway 71. About 45% of the 24,000-ac WMA is comprised of canyon grasslands.

MESIC MEADOWS are found in the Beaverhead Mountains and Idaho Batholith ecoregions; species present include: timber oatgrass (Danthonia intermedia);

tufted hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa).

PALOUSE PRAIRIES are found in the Palouse Prairie ecoregion; species present include: Idaho fescue; bluebunch wheatgrass (Pseudoroegneria spicata).

SUBALPINE AND ALPINE GRASSLANDS are found in the Beaverhead Mountains, Challis Volcanics, and Overthrust Mountains ecoregions; species present include:

slender wheatgrass (Elymus trachycaulus); rough fescue (Festuca campestris); Idaho fescue; greenleaf fescue (Festuca viridula);

spike fescue (Leucopoa kingii).

MOUNTAIN FOOTHILL AND VALLEY GRASSLANDS are found in the Okanogan Highlands, Owyhee Uplands, and Snake River Basalts ecoregions; species present include:

Indian ricegrass (Achnatherum hymenoides); red threeawn; squirreltail (Elymus elymoides); rough fescue; Idaho fescue; needle and thread;

basin wildrye (Leymus cinereus); western wheatgrass (Pascopyrum smithii); Sandberg’s bluegrass; bluebunch wheatgrass; sand dropseed.

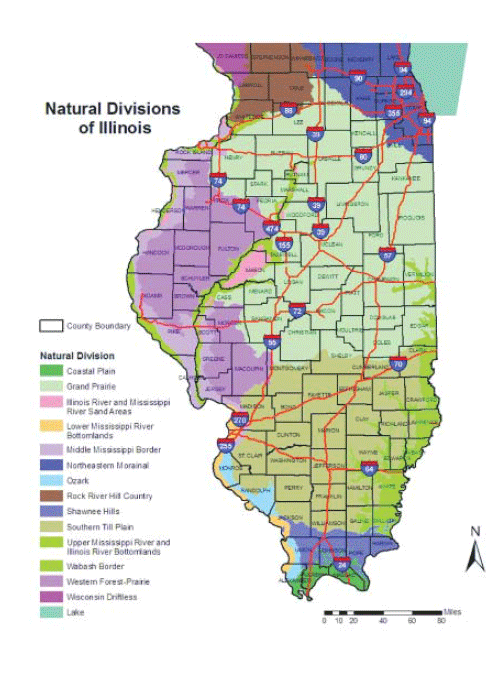

ILLINOIS ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Illinois contains 14 natural divisions which are classified natural environments and biotic communities based upon physiography (topography, soil and

bedrock), natural vegetation, climate, flora and fauna. Descriptions for each natural division can be found within the source cited here.

SOURCE:

Schwegman, J.E. 1972. Comprehensive Plan For The Illinois Nature Preserves System, Part 2 - The Natural Divisions Of Illinois. Illinois Nature

Preserves Commission, Rockford, IL. 32 pp. http://archive.org/details/comprehensivepla02illi

DNR CONTACT:

Natural Areas Program Manger Illinois

Department of Natural Resources

One Natural Resources Way

Springfield, IL 62702

Phone: 217-785-8774

http://dnr.state.il.us/conservation/naturalheritage/

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

The Prairie Ridge State Natural Area is found in Jasper and Marion Counties, SW of Newton. The site contains a mosaic of habitat types including native

remnant prairies, restored native grasses, wetlands, cool season grasses, habitats prepared by annual discing for brood-rearing of prairie-chickens and

other birds, woodlands/old fields, cropland being converted into grassland, and miscellaneous areas such as buildings sites and waterways. Management

of this area includes the development of grassland plant communities of native prairie species and introduced grasses. Wetland communities have been constructed

to provide habitat for 15 state threatened and endangered wetland dependent species. Directions: From State Highway 33 turn south on Bogota Road (990

N 900E) and go 4 miles to first curve in road. Go straight off curve to crossroads (600N 900E), turn left (east) for 1 mile or first crossroad (600N 1000E)

then turn right (south) and go 1 3/4 miles to white house with wire fence. http://dnr.state.il.us/orc/prairieridge/index.htm

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

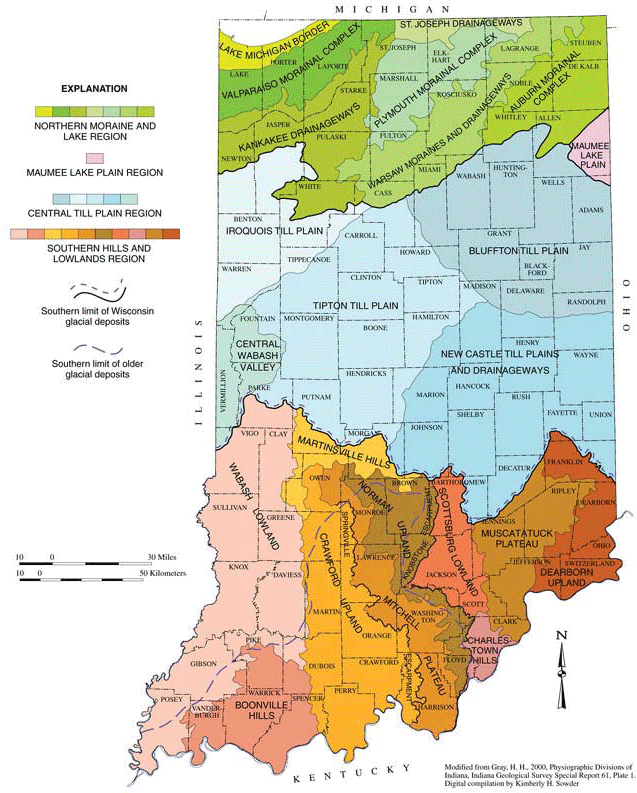

INDIANA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Indiana has six ecoregions which follow the USGS designations. These ecoregions include: Central Corn Belt Plains; Eastern Corn Belt Plains; Huron /

Erie Lake Plains; Interior Plateau; Interior River Valleys and Hills; and S. Michigan / N. Indiana Drift Plains.

SOURCE:

Homoya, Michael A., D. Brian Abrell, James R. Aldrich and Thomas W. Post. 1985. The Natural Regions of Indiana. Proc. Ind. Acad. Sci. 94:245-268.

Map Drafted by Roger L. Purcell, Indiana Geological Survey. http://www.naturalheritageofindiana.org/learn/regions.html

DNR CONTACT:

Heritage Program Coordinator Indiana Department of Natural Resources

Division of Nature Preserves

402 W. Washington St., Rm W267

Indianapolis, IN 46204

Phone: 317-232-4078

http://www.in.gov/dnr/naturepreserve/

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

The Hoosier Prairie, within the Northwestern Morainal Natural Region, is located east of U.S. 41 on Main Street in Griffith. This site contains dry black

oak savannas with mesic sand prairie openings on slopes between the rises and swales. Nearly 500 acres in size, this State Dedicated Nature Preserve is

managed by prescribed fire and mechanical removal of select trees and shrubs.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

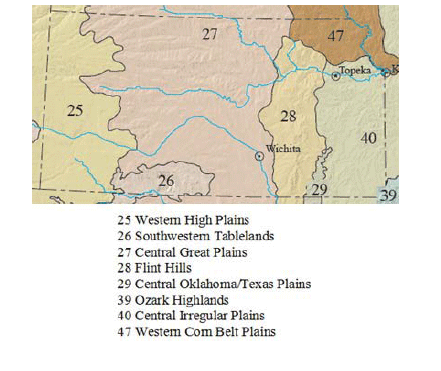

KANSAS ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Kansas is divided into 8 Level II ecoregions: 47 Western Corn Belt Plains, 40 Central Irregular Plains, 39 Ozark Highlands, 29 Central Oklahoma/Texas

Plains, 28 Flint Hills, 27 Central Great Plains, 26 Southwestern Tablelands, and 25 Western High Plains. Descriptions of each ecoregion can be found on

the web site listed under Source.

SOURCE:

US EPA https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions-north-america

CONTACT:

Community Ecologist

Kansas Natural Heritage Inventory

Kansas Biological Survey

2101 Constant Ave.

Lawrence, KS 66047-3759

Phone: 785-864-1500

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

Konza Prairie Biological Station, located approximately 13 km south of Manhattan, Kansas, is a 3487-hectare site dominated by native Flint Hills tallgrass

prairie. Owned by The Nature Conservancy and Kansas State University, it is operated as a field research station by the K-State Division of Biology. Habitats

include upland prairie on thin loess soils, hill prairie along alternating limestone benches and slopes, and lowland prairie on alluvial-colluvial soils.

Gallery forests dominated by bur and chinquapin oaks and hackberry occur along the major stream courses. Site access is limited; see

http://kpbs.konza.ksu.edu/.

The following are additional native grasslands found in the ecoregions of Kansas. This information is taken from the Kansas Native Plant Society web site

at http://www.kansasnativeplantsociety.org/ecoregions.php

39 OZARK HIGHLANDS: Spring River Wildlife Area, Cherokee Co. (undisturbed prairie meadow).

40 CENTRAL IRREGULAR PLAINS: Harmon Wildlife Area, Labette Co. (undisturbed prairie meadow); Ivan Boyd Memorial Prairie Preserve, Douglas Co., (tallgrass

prairie).

47 WESTERN CORN BELT PLAINS: Olathe Prairie Center, Johnson Co., (remnant prairie).

28 FLINT HILLS: Tallgrass National Preserve, Chase Co., (tallgrass prairie).

25 WESTERN HIGH PLAINS: Cimarron National Grasslands, Morton Co., (sandsage prairie).

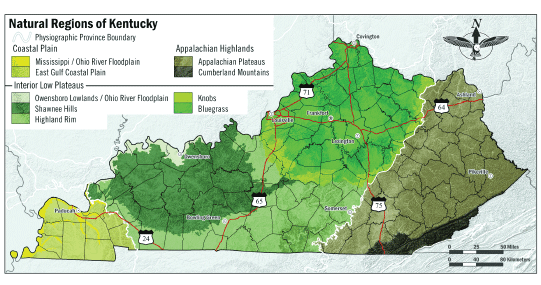

KENTUCKY ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Kentucky has three major physiographic regions, including: Coastal Plain, Appalachian Highlands, and Interior Low Plateaus.

SOURCE:

Evans, Marc and Abernathy, Greg. 2008. Natural Regions of Kentucky Map. Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission, Frankfort, Kentucky.

NPC CONTACT:

Heritage Branch Manager Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission

801 Schenkel Lane

Frankfort, KY 40601

Phone: 502-573-2886

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

Logan County Glade State Nature Preserve is 41 acres of limestone glades in Russellville, and has areas dominated by little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

and side-oats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula). A permit is required to access some areas. Located in Logan County: From the junction of the Green River

Parkway and U.S. 68/KY 80 at Bowling Green, follow U.S. 68/KY 80 west for 24.4 miles to Russellville. Turn right into parking area between Health

Department and old hospital. Additional grasslands in Kentucky’s State Nature Preserves and State Natural Areas system are listed at

https://eec.ky.gov/Nature-Preserves/Locations/Pages/default.aspx. Note that access to some areas is limited.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

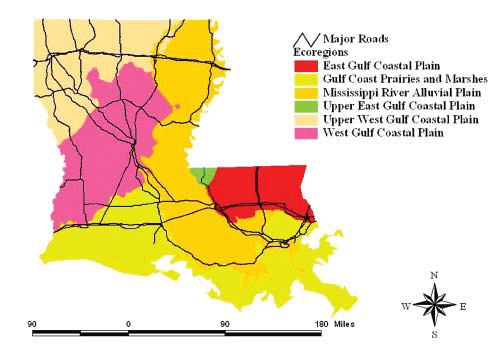

LOUISIANA ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Louisiana has six ecoregions which follow the designations by The Nature Conservancy. These ecoregions include: East Gulf Coastal Plain; Gulf Coast Prairies

and Marshes; Mississippi River Alluvial Plain; Upper East Gulf Coastal Plain; Upper West Gulf Coastal Plain; and West Gulf Coastal Plain.

SOURCE:

Louisiana Natural Heritage Program, http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/louisiana/explore/index.htm

CONTACT:

Botanist Louisiana Natural Heritage Program Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries

2000 Quail Drive

Baton Rouge, LA 70898-9000

Phone: 225-765-2800

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

Iowa-Fenton Prairie Remnant, located between Iowa and Fenton beside RR tracks on east side of US 165, North of junction with I-10. The Nature Conservancy

has a seed lease and is performing stewardship (chemical and mechanical control of woody vegetation plus burning) on this remnant prairie strip.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

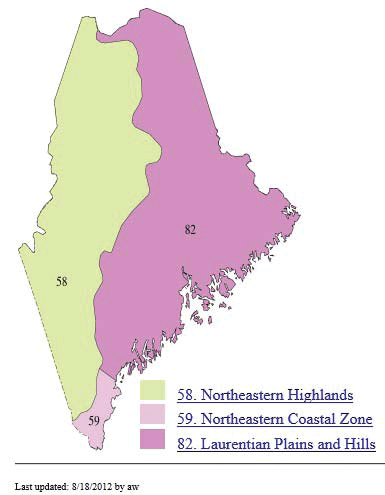

MAINE ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Maine contains three Level III ecoregions, following the designations by Omernik. These ecoregions include: 58. Northeastern Highlands; 59. Northeastern

Coastal Zone; and 82. Laurentian Plains and Hills.

SOURCE:

Omernik, J.M. 1987. Ecoregions of the conterminous United States. Map (scale 1:7,500,000). Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77(1):118-125.

https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/level-iii-and-iv-ecoregions-continental-united-states.

CONTACT:

Maine Natural Areas Program Natural Areas Division Department of Conservation

93 State House Station

Augusta, Maine 04333-0093

Phone: 207-287-8044 or 8046

Fax: 207-287-8040

Email: maine.nap@maine.gov

Web site: https://www.maine.gov/dacf/mnap/index.html

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

The largest native grassland in Maine, the Kennebunk Plains, is located 5 miles west of the Town of Kennebunk in the Northeastern Coastal Zone of southern

Maine. More information is available at

http://www.nature.org/ourinitiatives/regions/northamerica/unitedstates/maine/placesweprotect/kennebunk-plains.xml.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml

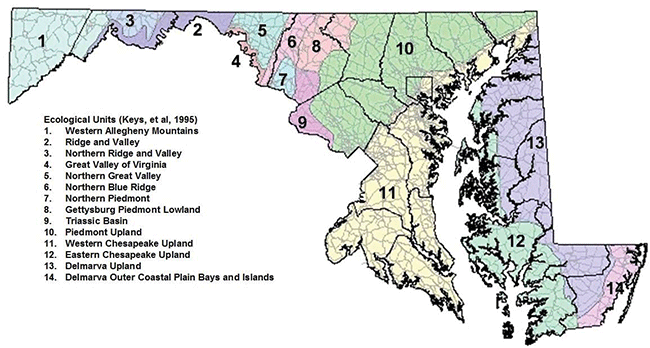

MARYLAND ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Maryland has 14 ecological units which follow the designations by the US Forest Service. These ecological units include: Western Allegheny Mountains;

Ridge and Valley; Northern Ridge and Valley; Great Valley of Virginia; Northern Great Valley; Northern Blue Ridge; Northern Piedmont; Gettysburg Piedmont

Lowland; Triassic Basin; Piedmont Upland; Western Chesapeake Upland; Eastern Chesapeake Upland; Delmarva Upland; and Delmarva Outer Coastal Plain Bays

and Islands.

SOURCES:

Harrison, J.W. 2007. The Natural Communities of Maryland: Draft. Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife and Heritage Service, Annapolis,

MD. Unpublished report. July 2007. 112 pp.

Keys, Jr., J.; Carpenter, C.; Hooks, S.; Koenig, F.; McNab, W.H.; Russell, W.; Smith, M.L. 1995. Ecological units of the eastern United States - first

approximation (CD-ROM), Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

GIS coverage in ARCINFO format, selected imagery, and map unit tables. Map created by Jason Harrison, October 2008.

DNR CONTACT:

MD DNR Wildlife and Heritage Service Headquarters

Tawes State Office Building

E-1 580 Taylor Ave

Annapolis, MD 21401

Phone: 410-260-8540

Fax: 410-260-8596

http://www.dnr.state.md.us/wildlife/

GRASSLAND EXAMPLES:

The Serpentine Barren, located at Soldiers Delight Natural Environmental Area, is approximately 1,900 acres of woodland and grassland savanna habitat

on serpentine soils. It supports native grasses and numerous rare plant species. Serpentine barrens are kept from succeeding to closed forests by periodic

fire, edaphic factors, and unstable substrates. Directions: Take I-795, to Franklin Blvd. West, right at Church Road, left on Berrymans Lane, then left

on Deer Park Road. More information is available at http://www.dnr.state.md.us/publiclands/central/soldiersdelight.asp.

VISIT A PRESERVE

In addition to Department of Natural Resource preserves called Scientific and Natural Areas (SNAs), the Nature Conservancy (TNC) manages preserves in

all 50 States and in more than 30 countries. These protected lands include some of the best remnants of plant communities of grasslands, wetlands and

woodlands for your information. TNC is the leading conservation organization working to protect ecologically important lands and waters for nature and

people.

Locate and visit a preserve near you to see adapted native plant associations to inform your own project site decisions. Use the preserves inventory list

as your shopping list to match plant species to your planting project.

To access TNC preserve data as a source for Google Maps, or as a layer for Google Earth, you can use their feed url --

http://www.nature.org/placesweprotect/preserve-map.xml.

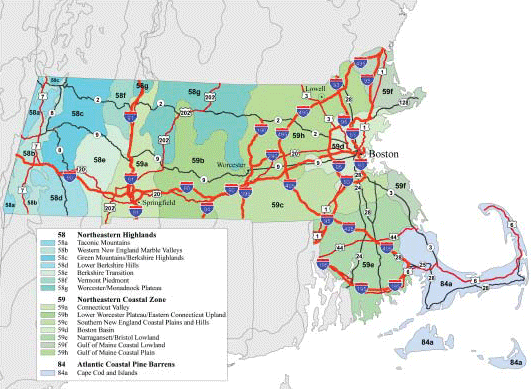

MASSACHUSETTS ECOREGIONS

ECOREGIONS:

Massachusetts has three Level III ecoregions which follow the designations by Omernik. These ecoregions are Northeastern Highlands; Northeastern Coastal

Zone; and Atlantic Coastal Pine Barrens. Each ecoregion has Level IV ecoregions within it. Descriptions of these ecoregions are available at https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecoregions.

SOURCE:

Dynamac Corporation (Under contract to USEPA)

200 SW 35th St.

Corvallis, Oregon 97333

CONTACT:

Massachusetts State Botanist

Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program

Division of Fisheries and Wildlife

1 Rabbit Hill Road

Westborough, MA 01581

Phone: 508-389-6360

Fax: 508-389-7891

Email: natural.heritage@state.ma.us

GRASSLAND EXAMPLE:

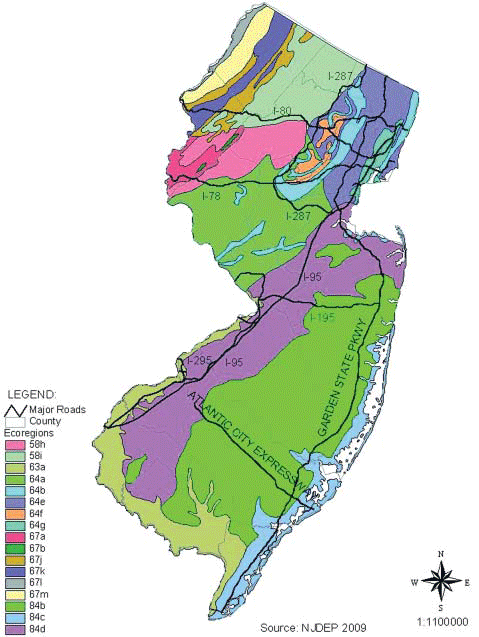

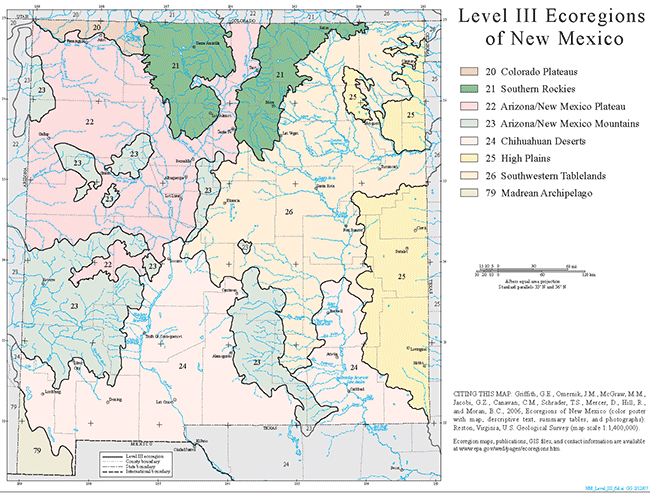

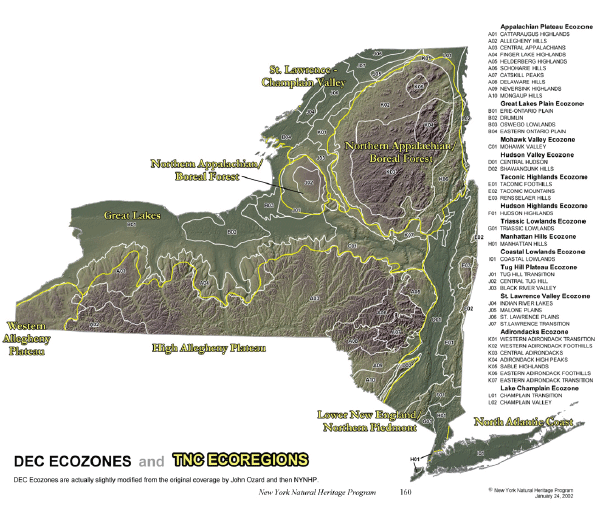

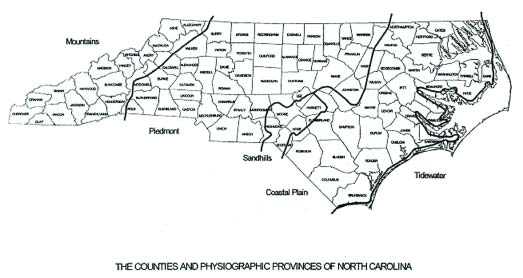

Katama Plains Preserve is located in Edgartown, Massachusetts on Martha’s Vineyard. Contact The Nature Conservancy for access. Katama is one of the few