PDF version (246KB)

FHWA

Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform

NEPA

Summary Report

December 31, 2009

Prepared for:

Federal Highway Administration

Tiering, Corridor, and Subarea Studies Group

Submitted by:

ICF International

9300 Lee Highway

Fairfax, Virginia 22031

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This report summarizes the FHWA Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA, held December 2 and 3, 2009 in Denver, Colorado. The peer exchange workshop examined the use of corridor planning studies as a foundation for NEPA decisionmaking. It highlighted several different approaches that states and metropolitan areas across the country have taken in the use of corridor studies. Peers shared lessons they learned and made recommendations on how best to use corridor planning to bridge the transportation planning and environmental review processes.

Participants to the peer exchange included representatives from FHWA; state departments of transportation; metropolitan planning organizations; Federal environmental resource agencies, and other interested stakeholders. Participants included both those in attendance and those participating remotely via Internet web conferencing. The peer exchange highlighted five different approaches on the use of corridor planning studies to inform the NEPA process.

The Parker Road Corridor Study is a pilot project that looked at potential transportation solutions for the increasingly congested and rapidly growing corridor between Hampden Avenue and E-470 in Denver, Colorado. From the outset, the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) worked closely with its resource agency partners, meeting face-to-face. Stakeholders identified a "worst case scenario" of potential environmental impacts to the corridor. Emphasis was placed on documenting transportation planning and environmental review linkages. Documentation proved beneficial to the success of the study including a matrix of resource agency comments and concerns. The open dialogue led to management-level support and the signing of a statewide partnering agreement.

CDOT

documented planning-level analysis it could use to inform subsequent NEPA analysis in a questionnaire. The questionnaire was included in the final study report so planning decisions might serve as a starting point for staff entering future NEPA studies.

The Interstate-83 Master Plan is a transportation planning study that acts as a framework to identify, plan, and program future transportation improvements for a section of Interstate 83 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The Master Plan includes an evaluation of existing and future traffic congestion, as well as safety characteristics for the corridor. It includes an inventory of environmental resources, though these were limited due to the urban setting. It also includes preliminary design concepts for improvements and a planning tool for future activities. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation realized that the cost of programmed projects for the corridor far exceeded available funding and therefore decided to divide the corridor into four independent sections, each with logical termini and independent utility. Each of the sections could be advanced through environmental review and programming on its own independent schedule. This flexible approach to corridor improvements, structured around independent sections, proved to be an efficient way to meet overall corridor transportation needs.

The Regional Outer Loop Corridor Feasibility Study is an evaluation of the need and feasibility of an outer loop network of transportation routes around the Dallas-Fort Worth region. The goal of the study is to identify a locally preferred corridor that may contain sections of independent utility, which could be studied further. The North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) is taking a "bottom up" approach to its stakeholder outreach, including engaging resource agency partners and utilizing technical environmental screening tools.

NCTCOG

is thoroughly documenting its outreach and planning decisions at this early point in time. As phasing for projects may be years down the road, NCTCOG is compiling a comprehensive history of alternatives development, analysis, and recommendations so planning decisions may be relied upon in subsequent NEPA studies and hopefully need not be revisited.

The US-20 Ashton to Montana State Line Corridor Plan is a long-range planning effort by the Idaho Transportation Department (ITD) to assess the condition of the US-20 Corridor and identify necessary improvements to meet the corridor’s system and user needs for the next 20 years. The plan built upon previous Idaho experience with corridor planning and integration with NEPA.

ITD

took a flexible approach to its corridor planning. It emphasized building partnerships and listening to the needs of its stakeholders. This led to a smooth transition from corridor planning to project design and construction, and the successful creation of a fish passage improvement that met community needs.

The Libby North Corridor Planning Study is an evaluation of an environmentally complex section of Highway 567 abutting Pipe Creek in Kootenai National Forest in northwest Montana. The purpose of the study was to develop a comprehensive, long-range plan for managing and improving the corridor. The approach that Montana Department of Transportation took during the study led to a complete reassessment of the corridor and a significant change in project scope – from a full reconstruction of the roadway to minor safety improvements. The result was a shift in the level of environmental documentation (class of action) from an environmental impact statement to a categorical exclusion.

The peer exchange concluded with a half-day roundtable discussion of lessons learned and recommendations. Among the lessons learned were that a flexible approach enabled by corridor planning studies is often best, especially when it comes to agency and stakeholder outreach. The value of documenting decisions for future integration with NEPA also became clear. Finally, the peers in the workshop recommended that future guidance on the use of corridor planning studies in NEPA be realistic and clear.

back to table of contents

Peer Exchange Program

On December 2 and 3, 2009, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) convened a Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA in Denver, Colorado, hosted by the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG). The workshop examined the use of corridor planning studies as a foundation for NEPA decisionmaking.1 It highlighted several different approaches that regions across the country have taken in the use of corridor studies. Peers shared lessons they learned and made recommendations on how best to use corridor planning to bridge the transportation planning and environmental review processes.

Participants included representatives from FHWA; state Departments of Transportation (DOT); metropolitan planning organizations (MPO); environmental resource agencies, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and U.S. Forest Service; and other interested stakeholders. Participants attended in-person (31 individuals) and via a remote connection (19 individuals). Remote participants called in through a teleconference line and viewed workshop presentations over the Internet through Web conferencing.

The peer exchange program extended over a day and a half. The first day consisted of multiple presentations and facilitated discussion. After introductory presentations, five examples of pre-NEPA planning studies served as the basis for group discussion. These examples were:

- Parker Road Corridor Study: a study of potential transportation solutions for the increasingly congested and rapidly growing Parker Road corridor between Hampden Avenue and E-470 in Denver, Colorado.

- Presenters: Colorado Department of Transportation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- I-83 Master Plan: a transportation planning study to identify, plan, and program future transportation improvements for an 11-mile section of Interstate 83 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

- Presenters: Federal Highway Administration, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation

- Regional Outer Loop Corridor Feasibility Study: an evaluation for a locally preferred corridor of transportation networks for a regional outer loop surrounding the Dallas-Fort Worth region.

- Presenters: North Central Texas Council of Governments, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- US-20 Ashton to Montana State Line Corridor Plan: a second phase corridor analysis commissioned to ensure that improvements between Idaho Falls and Montana are guided by a long-range plan.

- Presenters: Idaho Transportation Department, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Libby North Corridor Study: an evaluation of an environmentally complex 14-mile section of Highway 567 abutting Pipe Creek in Kootenai National Forest, Montana.

- Presenters: Montana Department of Transportation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service>

A facilitated discussion of the approach taken for each example followed every presentation. Participants who attended in-person as well as those who joined remotely had the opportunity to ask questions and make comments. The second half-day of the program included discussion on the use of corridor planning studies to inform NEPA, from the transportation planning agency perspective and the environmental resource agency perspective. The workshop concluded with a roundtable discussion of common challenges and opportunities that the peers identified and recommendations they would make for future activities.

back to table of contents

Background

Historically, federally-funded highway and transit projects in the U.S. flow from the statewide and metropolitan transportation planning processes (pursuant to 23

U.S.C.

134–135 and 49 U.S.C. 5303–5306). It is not a statutory role of the Federal agencies to advocate for any particular project over another, relying on the local planning process decisions made by state

DOTs

and

MPOs. These planning processes serve as the foundation for subsequent project-level decisions, including decisions where a proposed action may have an environmental impact. The role transportation planning has on our environment is therefore a critical one — a role that has been consistently supported on the Federal level.

In 2005, FHWA and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) issued joint guidance encouraging a stronger linkage between transportation planning and the NEPA process. Later that year, when

SAFETEA-LU2 was enacted, Congress revised the transportation planning laws (23 U.S.C. §§134 and 135) to require increased consideration of the environment in both statewide and metropolitan planning. Section 6001 requires MPOs to consult with resource agencies and discuss potential environmental mitigation. SAFETEA-LU Section 6002 recognizes that the purpose and need for a project can include carrying out a goal defined in a transportation plan.3 In 2007, FHWA and

FTA

issued final transportation planning regulations that implemented the SAFETEA-LU changes and further clarified the optional procedure for linking transportation planning and NEPA decisionmaking.4 The regulations strongly support the integration of transportation planning with NEPA environmental review. The regulations allow a state, MPO, or public transportation operator to use the results and decisions of planning (corridor and subarea) studies as part of their overall project development process under NEPA.

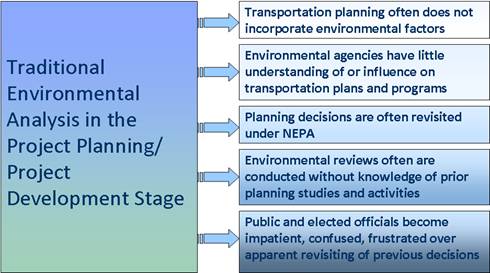

Despite statutory emphasis on the integration of planning with NEPA, traditional environmental analysis has often been conducted de novo – disconnected from the transportation analysis used to develop long-range plans, statewide/metropolitan Transportation Improvement Programs (STIPs/TIPs), and/or planning-level corridor and subarea studies. Ideally, NEPA analysis should add more specificity to planning decisions, not revisit decisions. This complicated approach often leads to information developed during NEPA that should more appropriately have been developed during planning, as well as other ensuing challenges (see graphic below).

In addition, there is often no overlap in personnel between the planning and NEPA stages of a project. Thus, there is a chance that a portion of the decisionmaking history could be lost in a linear hand-off or transition. Without adequate documentation at the planning level and knowing what planning stages a project has already been through, NEPA project teams can unknowingly perform redundant work. These complications often end up resulting not only in a duplication of work, but also extra expense, time, and confusion for the public and elected officials. The result is often a delay in implementing a needed transportation improvement. The 2007 transportation planning regulations looked to avoid all this, allowing for analysis from corridor and subarea studies to be relied on during environmental review.

In the time since the regulations went into effect however, few agencies around the country have actually used this authority or have explicitly called out their use as such. To understand fully how corridor planning studies are being used under this authority, FHWA convened the Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA. FHWA brought together a diverse group of peers from around the country and sought not only better understanding of the state of the practice, but also the best means by which to communicate guidance on this streamlining opportunity. The goals of the peer exchange were to:

- Share successes on the use of planning studies as a foundation for NEPA;

- Document lessons learned and any recommendations; and

- Inform development of future FHWA guidelines and/or reauthorization proposals.

Tiering, Corridor, and Subarea Studies Group

To explore the extent to which agencies are exercising the streamlining envisioned in the 2007 transportation planning regulations, FHWA created the Tiering, Corridor, and Subarea Studies (TCS) Group. The

TCS

Group is a subgroup to the Integrated Planning Work Group (IPWG) for Executive Order 13274: Environmental Stewardship and Transportation Infrastructure Project Reviews. The Executive Order established an Interagency Task Force that consisted of representatives from U.S. Departments of Transportation, Interior, and Agriculture, and EPA. The Task Force charged the IPWG with identifying the challenges and opportunities inherent to integrated planning – the linkage that occurs when transportation agencies and environmental resource agencies effectively coordinate their planning processes.

Over the past few years, the

IPWG

has played a significant part in exploring how transportation agencies consider environmental concerns early in the planning process and work with partner resource agencies to identify strategies to maximize environmental protection and transportation benefits. For instance, in 2005, the group produced the Baseline Report and Preliminary Gap Analysis, which identified three levels of recommendations for consideration by the Interagency Task Force. The TCS Group was asked to focus on the use of planning studies, to document the state of the practice, and identify recommended practices to better link the transportation planning and NEPA environmental review processes.

For the peer exchange, the TCS Group researched examples from around the country where planning studies are informing the NEPA process. It recommended five examples to highlight at the workshop. The examples were diverse enough that the peers would have an opportunity to learn from each other, especially how different approaches are used throughout the country. The TCS Group selected participants to represent the examples based on their experience and knowledge. The TCS Group sought to ensure a balanced agency perspective at the peer exchange, reflecting transportation planners, resource agency representatives, and NEPA practitioners.

Corridor Planning

The use of corridor planning studies to inform NEPA is not new. Rather, it is consistent with traditional transportation planning practice. Corridor plans can be prepared by a state DOT, an MPO, or a transit operator as part of the statewide or metropolitan planning process. Corridor plans bring together multiple disciplines, including transportation, community planning, environmental planning, and finance. Corridor plans identify the current functions of a corridor and forecasted demands. Although each corridor plan is unique based on the corridor, certain commonalities across plans exist (see box below).

Corridor plans typically include:

- The reason of the study, including the main system performance issues and forecasted demand;

- A clear definition of the study area, boundaries, and stakeholders;

- A description of corridor resources;

- A list of expected products coming out of the study, such as a description of future improvements or proposed investment;

- A proposed timeline for completion and key milestones; and

- A budget and resource allocation plan (e.g., scope of public involvement expected)

Guidance encouraging the use of corridor plans to inform NEPA dates back at least a decade to the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21). In 1999, the National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) released Report 435, Guidebook for Transportation Corridor Studies: A Process for Effective Decision-Making5, which provides practical tools and guidance for designing, organizing, and managing corridor and subarea studies. The Guidebook brings together lessons learned from experiences in different regions of the country and from studies with different scopes and levels of complexity.

The 2007 transportation planning regulations build on this guidance, encouraging corridor planning. The regulations define criteria that a Federal agency must consider in deciding whether to adopt planning-level analysis or decisions in the NEPA process, including involvement of interested state, local, tribal, and Federal agencies; public review; reasonable opportunity to comment during the planning process; and appropriate levels of documentation. Taken together, corridor planning can now be used to produce a wide range of analyses or decisions for adoption in the NEPA process for an individual transportation project, including:6

- The foundation for purpose and need statements;

- Definition of general travel corridor and/or general mode(s);

- Preliminary screening of alternatives and elimination of unreasonable alternatives;

- Planning-level evaluation of indirect and cumulative effects; and

- Regional or eco-system-level mitigation options and priorities.

Despite the issuance of the regulations, certain challenges and questions remain. These include:

- What conditions would benefit most from a planning-level corridor study?

- What level of environmental analysis is appropriate in planning-level corridor studies?

- What level of stakeholder/ public/ agency involvement is necessary?

- How can agencies ensure that the work conducted within planning studies will be recognized as valid within the NEPA process?

- When are resource agencies engaged in the planning process? To what extent does their early involvement influence the decisionmaking process?

- What challenges are agencies encountering when they rely on corridor studies?

- How can agency personnel get their management to accept the use of corridor planning in NEPA?

The peer exchange was designed to help address these challenges and highlight approaches that may overcome them.

back to table of contents

Day One Presentations

This section presents a summary of the presentations given on day one at the Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA. Each presentation was supplemented by a facilitated discussion.

Welcome and Overview

Jim Cheatham, FHWA; Gregory Nadeau, FHWA; Michael Culp, FHWA

Jim Cheatham, Director of the Office of Planning, opened the peer exchange stating that FHWA sees the workshop as one effort to reduce the time it takes to deliver a transportation project. FHWA hopes to hear of best practices by the peers so it could help inform others how best to link planning and NEPA.

Deputy Administrator Nadeau described the FHWA Administrator’s Innovation Initiative, Every Day Counts. The initiative’s mission is to identify and deploy readily available innovation and operational changes that will make a difference, incorporating a strong sense of urgency; and to identify policy or operational changes required to advance system innovation in the longer term. The initiative asks how to deploy innovation so overall improvements could be made. Every Day Counts has three initial core elements: (1) improving project delivery; (2) accelerating innovative technology deployment; and (3) going greener. FHWA will work with external stakeholders, state DOTs, and MPOs to shorten the time it takes to deliver highway projects (e.g., by incorporating planning analysis into NEPA). FHWA will seek to deploy innovations that are demonstrated, especially with regard to safety. Finally, FHWA will seek to lower its carbon footprint and reduce day-to-day operational costs. The goal of Every Day Counts is not just to expedite the process, but also to enhance the quality of a project and its surrounding environment. One of the principal tools for this is corridor planning. The results from this peer exchange will provide FHWA with needed information and shape future guidance. Stakeholder participation is critical here; FHWA has created a dedicated email account, everydaycounts@dot.gov, to receive input from external stakeholders. A Web platform to provide additional information is planned.

Michael Culp, with the Office of Project Development and Environmental Review, outlined the goals for the peer exchange: to collectively share and learn how planning studies are used today; to document lessons learned and make recommendations for future activities; and to inform FHWA on updated guidelines that could show how to better link planning and NEPA. This peer exchange focuses on the handoff from the planning process to the NEPA process, so we could avoid a duplication of effort, time, and money. The 2007 planning regulations are not just supportive of this. They give authority to DOTs and MPOs to link planning and NEPA. Thus, planning decisions — as long as they meet certain criteria – should be the foundation for project-level decisionmaking.

Legal Perspective on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA

Brett Gainer, FHWA; Jack Gilbert, FHWA

Representatives from the FHWA Office of Chief Counsel addressed the level of legal risk involved in taking planning products and using them in the NEPA process. When FHWA/FTA and their state or local partners incorporate planning decisions into NEPA, this should not be viewed as "NEPA-izing" planning. Instead, this process simply incorporates planning into the Federal decisionmaking process. Using planning to inform NEPA should not expose state and local agencies to any higher risk of litigation. The FHWA/FTA planning and NEPA regulations, and their underlying statutory framework, are intended to shield local planning decisions from NEPA litigation in Federal court.

The FHWA/FTA guidance on linking planning and NEPA done in 2005 (now included as Appendix A in the 2007 regulations) shows the proper ways to utilize information developed at the planning level in project-level or corridor-level NEPA documents. It includes conditions under which such information could be incorporated into NEPA (e.g., early public involvement, etc.). When properly-developed local planning information is incorporated into a NEPA document, that material is "federalized," and the agencies that are at risk for challenge in Federal court are the Federal decisionmakers.

Planning is not NEPA; it is not a major Federal action so agencies should feel secure that they are shielded from litigation. Nevertheless, state and local agencies should realize that anyone could file a lawsuit. From the perspective of a litigator, the question is whether that person can prevail. Taking certain steps in anticipation of litigation is wise. Agencies should note the importance of the administrative record and be sure to include all relevant material in the record. It is important to remember that Federal judges only get to look at the administrative record when considering the sufficiency of a NEPA document. If planning analysis is not in the administrative record, then the court has no way of knowing it was done. Documentation should show what information was used, the source of that information, who used it, and how it was relied upon. The more documentation one includes, the better. But even with the best documentation, you can still be sued and lose. Therefore, the best advice is to get your counsel’s office involved early in the process. If you do the work and show it in the documentation, you can shorten the NEPA process.

Parker Road Corridor Study

Lizzie Kemp Herrera, CDOT; Jon Chesser, CDOT; Alison Michael, FWS

The Parker Road (SH 83) Corridor Study was a pilot project that looked at potential transportation solutions for the increasingly congested and rapidly growing Parker Road corridor between Hampden Avenue and E-470 in Denver, Colorado. The study was only the second Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) study done by Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT). Before

PEL

studies became common, CDOT would identify a corridor vision and project priorities but the state would often revisit theses decisions when the project got to the NEPA stage. CDOT now views the PEL approach taken for the Parker Road Study as a more efficient process.

Figure 1: Photo of Parker Road

Parker Road is a suburban corridor, running diagonally from Denver County southeast along Cherry Creek State Park to Arapahoe County. Parker Road is a major regional arterial that provides direct access to downtown Denver. Corridor improvements had to balance regional mobility needs with local access for businesses and residents. Affected resources included parks, wetlands, historic properties, and listed species. Although CDOT had limited funding, it wanted to identify improvements for the entire corridor within the context of how Parker Road operates. From the outset, CDOT worked closely with its resource agency partners, FHWA, and local project sponsor, Arapahoe County. CDOT had early and broad resource agency involvement because it wanted to know upfront the environmental issues of concern. CDOT met face-to-face with each of its partners and identified a "worst case scenario" of potential impacts that improvements would bring to the corridor. The agency also conducted and documented a significant amount of public involvement.

CDOT documentation included a PEL matrix, which was a summary of agencies’ expectations and concerns about proposed corridor improvements. The matrix provided mutual understanding of the conditions under which findings made during planning could flow directly into NEPA. The open dialogue led to management-level support by agencies and an eventual signing of a PEL partnering agreement. The partnering agreement is a statewide agreement of 15 signatory agencies committed to the principles of PEL. The agreement does not supersede each agency’s own legal responsibilities. CDOT documented the entire Parker Road Study process in the PEL questionnaire developed jointly by FHWA Colorado Division Office and the project team. The questionnaire documents planning-level analysis that could be used in NEPA (e.g., level of public involvement, resource agency engagement, identified impacts, etc.). When a PEL study is started, this questionnaire is given to the project team. CDOT bound the questionnaire into the final study report so planning decisions might serve as a starting point for staff entering future NEPA studies.

CDOT sees a number of benefits from the PEL process it followed for Parker Road. The process sets the context for large corridors and gives broader understanding of decisions resulting in better projects. Smaller projects benefit too. CDOT found projects with corridor plans clear NEPA with minimal backtracking. PEL allows project improvements to be studied in a logical sequence (i.e., a strategic phasing of improvements are studied). It encourages the cross-training of planners and environmental practitioners. Planners learn more about environmental resources and vice versa. Early involvement allowed resource agency concerns to be addressed in scoping and early alternatives analysis rather than later in the process. Finally, PEL is less expensive, less time-consuming, and less resource-intensive than a more traditional linear review/hand-off transition.

As a result of the Parker Road Study, there were a number of lessons learned. In order for PEL to work for future NEPA studies, cumulative impact analysis should be done. While the Parker Road Study did not assess cumulative impacts, CDOT feels the appropriate time to look at cumulative impacts is at the corridor level. CDOT also learned that not all agencies want to be involved in the same way, or at the same time. For example, EPA chose not to be involved early, while FWS chose to be involved early so it could help select alternatives. Finally, some resource agencies are also landowners and have a dual interest. In this case, Cherry Creek State Park acted as both an interested party and resource agency.

Interstate-83 Master Plan

Deborah Suciu Smith, FHWA; John Bachman,

PennDOT; Mike Keiser, PennDOT

The Interstate-83 Master Plan is a transportation planning study to identify, plan, and program future transportation improvements for an 11-mile section of Interstate 83 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Interstate 83 extends from I-81 just northeast of Harrisburg to downtown Baltimore, Maryland. It is an important link in the National Highway System and a vital component of local access in and around the greater Harrisburg metropolitan area. Interstate-83 is a true urban corridor. It was built in the 1950s and ’60s. Today, the corridor is highly populated and bordered by a number of commercial and residential properties. It is also a major freight corridor and frequently experiences heavy congestion. In Cumberland and Dauphin Counties, I-83 forms a major part of the Capital Beltway, which also includes I-81 and PA 581. The area of I-83 involved in the Master Plan study is the northernmost 11 miles, which includes the section that extends around the City of Harrisburg and up to 13 interchanges.

The Master Plan evaluates existing and future traffic congestion, as well as safety characteristics for the corridor. Safety is a major concern as the highway was designed to 1960s standards. It lacks proper acceleration/deceleration lanes and shoulders/medians are minimal to nonexistent. Early 1960s-era transportation studies did not anticipate current travel demand thus the interstate is reduced to a single lane at two major interchanges. Due to its age, much of the pavement and bridges have deteriorated. This has led to high crash rates and multiple fatalities. The plan also includes an inventory of environmental resources. After discussions with the resource agencies, environmental concerns were limited due to the corridor’s urban setting. Issues included water quality in the Susquehanna River, local parks, air quality, noise, historic properties, and three cemeteries. Environmental Justice concerns were also raised. Finally, the plan developed preliminary design concepts for improvements and established a planning tool for future activities.

When considering corridor improvements, Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) originally anticipated it would have to do one large environmental impact statement (EIS) for the entire corridor. However, a closer look revealed that different locations within the corridor had different needs. Moreover, PennDOT (working with the local MPO) realized that the cost of programmed projects for the corridor far exceeded available funding. Therefore, PennDOT decided to divide the corridor into four independent sections, each with logical termini and independent utility. Each of the sections could be advanced through environmental review and programming independently on its own schedule. This flexible approach to corridor improvements, structured around the needs and recommended improvements for each section, enabled PennDOT to meet overall corridor transportation needs more efficiently. The Master Plan then is essentially a framework for all partners to use in the future. As funding becomes available, prime sections of I-83 could be improved.

The I-83 Master Plan illustrates an issue that is becoming more common around the country. Agencies may frequently be in the process of performing NEPA analysis on transportation projects when there is a lack of funding to implement the projects. Agencies are starting the NEPA process for projects earlier than they should be considering funding realities. Corridor planning can help agencies identify transportation and environmental needs cost-effectively in a corridor study without entering a costly NEPA study or risking the analysis becoming outdated and old prior to project implementation. Corridor planning also allows projects to be prioritized and to identify what can feasibly be funded before extensive NEPA analysis is done.

Among lessons learned from the study, FHWA recommended that an in-depth safety review of the corridor be done first. As public safety was a principal driver for the plan, FHWA would have liked to see earlier identification of potential corridor safety improvements. Stakeholders also questioned whether the timing and level of public involvement was appropriate. When FHWA and PennDOT did public outreach on the plan, the public naturally wanted to see more immediate results in the form of safety improvements or congestion relief.

Regional Outer Loop Corridor Feasibility Study

Sandy Wesch, NCTOG; Sharon Osowski, EPA

The Regional Outer Loop Corridor Feasibility Study is an evaluation for the Dallas-Fort Worth region of the need and feasibility for a transportation facility to aid regional mobility, address increased freight flows, and enhance economic vitality at a regional level. This 240-mile regional Outer Loop would be a network of transportation routes that could incorporate existing and new highways, railways, and utility right-of-ways. North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) divided the Outer Loop corridor into 17 subareas that have major transportation facilities to see if sections of independent utility could be identified.

The goal of the study is to:

- Identify a half to one-mile wide Locally Preferred Corridor (LPC) for further study, which may or may not form a loop or be continuous around the region;

- Identify Sections of Independent Utility (SIU); and

- Identify timing and phasing (i.e., main lanes, access roads, corridor preservation) for each

SIU.

The study is still in its early stages. NCTOG has identified transportation needs, problems, and goals; but has only just begun to collect data and develop alternatives. NCTOG is taking a "bottom up" approach to integrate stakeholder outreach. It began outreach early on. Its outreach has been diverse, including stakeholder roundtables, public meetings, and consultation with partner agencies. It has tried to identify where new development may occur and opportunities exist. NCTOG has engaged resource agencies through the Transportation Resource Agency Consultation Environmental Streamlining (TRACES) initiative, a regional effort to improve communication and consultation with environmental resource agencies considered stakeholders to the transportation planning process. NCTOG is collaborating with resource agencies for their expertise, technical tools, and the wealth of information they bring.

Some of the technical tools that NCTOG is using include:

- Regional Ecological Assessment Protocol (REAP): a planning and screening level assessment tool that uses existing GIS (geographic information system) data to classify land based on ecological importance;

- GISST: a

GIS-driven environmental assessment and data management tool that uses over 100 different types of environmental resource criteria to score and assess potential environmental impacts; and

- NEPAssist: an innovative Web-based tool that draws environmental data dynamically from EPA regions’ GIS databases and provides immediate screening of environmental assessment indicators for a user-defined area of interest. These features contribute to a streamlined review process that potentially raises important environmental issues at the earliest stages of project development.

NCTOG has been methodical in its documentation of the feasibility study. The study’s guiding principles, objectives, and performance measures are all clearly documented. The agency created a database that tracks public comments and response. This helps preserve a project history in case there is staff turnover, as well as builds an administrative record for future environmental reviews. Because the implementation of phases of the overall corridor may be 20 years or more in the future, NCTOG is being careful to document the date and source for all information. The agency is compiling a comprehensive history of alternatives development, analysis, comments, and recommendations based on today’s best available information. The history will be included in the final study and allows planning decisions to be relied upon. Hopefully, these will not be revisited in future NEPA processes.

NCTOG faces a number of challenges with the study. First, NCTOG needed to develop a travel demand model that could properly analyze the vast information it was collecting. The agency’s original travel demand model was based on five counties. NCTOG needed a forecasting model that would represent 12 counties, which encompasses the corridor study area. The agency has to manage stakeholder and public expectations. The public is eager to know the exact location of the alignment. Local governments focused on development and land use are especially eager for specifics. They have trouble understanding that the point of the study is to identify an

LPC, not specific alignments. NCTOG has to create a regional purpose and need that is flexible enough to accommodate a project-level purpose and need. NCTOG realizes that when specific projects are being proposed, proponents will look back to the study and rely on its analysis. The agency also has to be careful in recommending an LPC which may conflict with an alignment already selected by a local jurisdiction. Another challenge is whether to use existing facilities versus new alignment ("Greenfield"). Some current facilities will be unable to handle future travel demand, thus new facilities will be needed. How do you balance this need with the impact to natural resources? This study also raises the debate over whether NCTOG is encouraging sprawl rather than accommodating growth. Does planning for a regional outer loop encourage urban sprawl? A final challenge is their relationship to the Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC). NCTOG has had to distinguish this study from the TTC.

US-20 Ashton to Montana State Line Corridor Plan

Bill Shaw, ITD; Elaine Somers, EPA

The US-20 Corridor Plan, from Ashton Hill Bridge to the Montana State Line, is a long-range planning effort by the Idaho Transportation Department (ITD) to assess the condition of the US-20 Corridor and identify necessary improvements to meet the corridor’s system and user needs for the next 20 years. The US-20 Corridor, from Ashton to the Montana border is a critical gateway to Yellowstone National Park and Henry’s Fork of the Snake River. US-20 is predominantly a two-lane rural highway with occasional passing lanes (though current shoulder widths present a safety concern) that runs north out of Ashton, Idaho through the Targhee National Forest to the Montana State line. The corridor encounters heavy tourist traffic, local traffic, and the majority of freight movement between West Yellowstone, southern Montana, and the Snake River plain.

ITD’s District 6 office led the US-20 Corridor Plan. It stressed having an iterative, ongoing planning process that focused on listening to stakeholders, capturing needs, and normalizing the planning process so better decisions could be reached. Improvements that the district identified included building shoulders, lane markings, paving, and ensuring access to the many local businesses along the corridor.

The district office anticipated certain environmental issues. Specifically, this meant ensuring passage for Cutthroat Trout to their traditional spawning grounds. The Cutthroat is the state fish of Idaho and enjoys renowned popularity. The district was willing to address fish passage but funding for improvements was limited and so it felt it had few options. When fish concerns continued to dominate the conversation, the district formed an action team of experts experienced in issues of mitigation, stream-banking, and permitting. The office worked with resource agencies to catalog stream crossings. ITD recognized that concerns over fish passage formed a legitimate need. The office supported advocates within the action team to try to find suitable funding. When the action team found the funding, ITD took the team that it brought together for one purpose and redirected it. This flexible approach led the district to replace culverts with a bridge, returning the Targhee Creek to its natural flow, and allowing enhanced fish passage. In short, the district’s corridor planning process and action team permitted a smooth transition from corridor planning to project design and construction when funding opportunities changed.

ITD has six district offices. While all six are rather autonomous, corridor planning is embraced throughout the state. In 2006, the state updated its Corridor Planning Guidebook7 which is designed to integrate transportation planning with land use planning, coordinate local and state transportation planning efforts, and facilitate the development of context sensitive solutions. The state also developed the Idaho Corridor Planning and NEPA Integration Guide8 which describes five different approaches to integrating planning and NEPA – ranging from a fully integrated corridor plan, where NEPA is part of the work effort, to a pre-corridor planning/NEPA approach for projects that have not been designated as part of a corridor plan. Each approach summarizes the relative advantages, disadvantages, and conditions under which the approach is most applicable.

U.S. EPA, Region 10, suggested that a Notice of Intent (NOI) could be issued concurrently with a corridor planning study – that is, that corridor planning be done as part of the NEPA process. EPA, Region 10, stated that it sees advantages to this approach, bringing people to the table and raising attention via the NOI. In addition, EPA recommended that planning agencies follow regular consultation procedures and consider whether to establish an interagency memorandum of agreement with formal concurrence or consultation points. Agencies should ensure each resource agency and Tribe is invited to participate from the beginning. Agencies can overcome resource constraints by creating ways to enable participation, particularly for more distant participants, such as via site visits, teleconference, videoconference, environmental forums, electronic communication, clustered meetings/site visits, and other means. Public involvement should include all stakeholders and affected entities. Agencies should use the guidance from Appendix A and, at a minimum, instill check-in points for comment and consultation. Agencies should determine the best means of documentation and use origin/destination studies to inform planning. Finally, corridor planning should be inclusive, manageable, and appropriately iterative — resulting in more informed decisionmaking, per the intent of NEPA.

Libby North Corridor Study

Jean Riley,

MDT; Scott Jackson, FWS

The Libby North Corridor Study is an evaluation of an environmentally complex 14-mile section of Highway 567 abutting Pipe Creek in Kootenai National Forest in the Cabinet-Yaak Mountains of northwest Montana. The purpose of the study was to develop a comprehensive, long-range plan for managing and improving the corridor. Highway 567 runs between the City of Libby and the community of Yaak and lies within a Grizzly Bear Distribution Area.9 Highway 567 is a two-lane roadway functionally classified as a rural major collector and is part of the Montana Secondary Highway System. The roadway provides access to Forest Service lands for skiing, hunting, camping, and hiking activities and has historically been used for logging; a use that continues today. The road is substandard, in some areas only 15 feet wide, with deficient sight lines. It has a crash severity rate more than double the statewide average for rural roads in Montana. Improving this corridor therefore became a priority. The Libby North Corridor Study evaluated existing conditions and determined what, if any, improvements could or should be made.

Figure 2: Photo of Pipe Creek Road

Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) led the study. Montana has been a national leader among state DOTs in the use of corridor studies, having completed six studies with nearly that many currently in the pipeline. For the Libby North Corridor, originally MDT had a project concept in mind. MDT was planning to reconstruct the road to current standards. If this project had been developed under traditional methods, beginning with a formal NEPA environmental review, a full

EIS

was likely. However, an EIS would have cost three to eight times more than what MDT had budgeted. Plus, there were serious endangered species concerns (Grizzly Bear, Bull Trout, etc.). Thus, MDT was concerned that environmental sensitivities related to any reconstruction could prevent the implementation of the project.

After coming to this realization, MDT decided to reassess the corridor at the planning level to obtain a better understanding of corridor limitations and needs. MDT took a "10,000-foot" view to its analysis. It looked at major concerns rather than specific issues. It asked are there wetlands, are there endangered species, and are there historic features?

MDT reengaged the community for its study. At public meetings, it soon became apparent that a full reconstruction was inconsistent with what the community valued. The public’s main concern was certain safety improvements; it did not want the roadway to change in character. It liked the slow speeds and circuitous winding nature. MDT also met with resource agencies who wanted the minimum impact possible to the surrounding environment. During meetings, stakeholders discussed improvement options. All discussions were documented and recommendations noted. Once a range of recommendations was developed, discussion turned to proposed build alternatives and improvement options. Working with its partners, MDT identified improvements that would not only improve public safety but also met environmental goals.

The approach MDT followed was unique. MDT obtained information from the public and resource agencies prior to initiating formal environmental review. Because of the significant change in the scope of the project — from a full reconstruction of the roadway down to a minor widening and alignment change — the project will have much less of an environmental impact. With this reduction in impact to the environment, MDT was able to avoid a costly EIS and instead conduct a categorical exclusion (CE).

Among lessons learned, the study showed that corridor planning could lower environmental review costs in several ways. These include:

- Reducing impractical or unreasonable alternatives from further evaluation;

- Scoping the project at a level consistent with local wants and needs;

- Identifying fatal flaws in planning prior to initiating the NEPA process; and

- If public opposition exists, then identifying strategies to address the opposition may eliminate further environmental review costs.

The Libby North Corridor Study was completed within 18 months and cost approximately $330,000. The total cost of the study and CE was anticipated to be one-third to one-fourth the cost of traditional MDT practice. In addition, the study demonstrated to MDT that resource agencies are willing to contribute to planning-level studies where appropriate. This has led to an improved relationship between MDT and its partner resource agencies. Finally, the study showed that the public is receptive to this type of approach. MDT met with the public first to bring it into the decisionmaking process. People appreciated the opportunity to express their concerns. This early engagement helped determine the most critical needs for the roadway.

back to table of contents

Day Two Roundtable Discussion

On the second day of the peer exchange, participants first engaged in a presentation that recapped some of the common themes heard throughout day one. These included:

- Funding and staffing at resource agencies and DOTs is limited

- Corridor planning can build long-term process efficiencies

- Document all decisions. Continually build the administrative record.

- More user-friendly language/ nomenclature can be useful

- Use of readily available Web tools and GIS data

- Indirect and cumulative effects are rarely addressed in planning studies

- Relationship-building is a cornerstone to successful integration of planning and NEPA processes

- Early public and agency involvement is critical

- Questions remain on how best to engage resource agencies and when they should be engaged

- Establish roles, responsibilities, and expectations among stakeholders

- What started as a pilot can lead to standardized agency procedures

- Realized benefits of corridor planning informing NEPA, include:

- Better environmental outcomes/ impact avoidance

- Cost, time savings

- Builds relationships for long-term

- Achieves buy-in from stakeholders

- Flexibility in planning — not all or nothing

- Legally sufficient

- Upfront work leads to overall efficiencies downstream

- Continued challenges remain, including:

- Fiscal challenges for resource and transportation agencies — need to seek out innovative agreements/ mechanisms

- Need to incentivize this approach — worst case scenario (and what else?)

- Changes will occur — acknowledgement that this is a planning study, not NEPA

- Ensuring the continued validity of analysis/data

- Role of regional planning in evaluating indirect and cumulative effects

- Coordinating transportation planning and project development with land use decisionmaking

Figure 3: Photo of Peers

Peer exchange participants then took part in a facilitated discussion that contrasted the transportation planning agency perspective on the use of corridor planning to inform NEPA with the resource agency perspective. A summary of the common discussion points is below.

The motivation for corridor planning varies. For transportation agencies, corridor studies make sense when...

- There is planning money available. For example, CDOT had a funded project that happened to coincide with the release of the planning regulations and a Linking Planning and NEPA workshop.

- The study is conducted for large projects or for projects with delayed phasing. NCTOG engaged in corridor planning primarily to understand the sheer magnitude of their project.

- There is an opportunity to learn. MDT used it while they were waiting to see what effect a lawsuit would have involving the Grizzly Bear Distribution Area.

- The planning study could reduce project costs (e.g., as with Montana and Pennsylvania).

- There are questions about the level and timing of project funding. In order to spend money in an incremental way, you have to think through some of these issues. If you want to move forward with project development, it helps to be able to point to information gathered in completed planning studies.

- You have the staffing resources available. For example, Idaho was given new positions and charged with improving their project delivery, which resulted in their corridor planning process. Montana and Colorado also have funded resource agency positions that can participate at a higher level.

- There is regulatory support or guidance encouraging the use of corridor studies. ITD questioned whether it was on the right path but having FHWA participate in each of its corridor planning meetings helped and the supporting Federal regulations indicated they were on the right path.

- Commitment or consensus can be difficult, but modifying a planning study is likely easier than modifying a NEPA decision. Thus, the flexibility of corridor planning may make agreement on issues easier to achieve.

For resource agencies, corridor planning is an opportunity to have early impact on a project’s direction as long as...

- Resource agencies can help in the minimization and avoidance of impacts.

- They have personnel available, whether through funded positions or not.

- There is a tangible benefit realized. EPA, Region 6 got involved because EIS’s were submitted on an ad-hoc basis. They witnessed an improvement in the environmental documentation when they were involved early in the process.

- There is a demonstrable time savings. EPA has a statutory responsibility to review all EIS’s, even projects that have a limited chance of being implemented. Their incentive to participate increases if they see fewer, more focused NEPA studies and/or an increase in NEPA documents for projects with a better chance of being implemented.

- The relationship with the planners is there. If resource agencies know who to call (and vice versa), they will be more likely to participate.

- There is a written agreement or management support for their involvement. CDOT has the statewide partnering agreement and NCTOG is involved in TRACES, both encourage early participation of the resource agencies.

- Planning improves NEPA. For example, on an I-70 Colorado programmatic EIS, there were 21 alternatives analyzed. A planning process before this could have focused the alternatives analysis and reduced the number of alternatives to a more manageable number.

Challenges remain for all, such as...

- Determining the appropriate level of analysis detail. NEPA reviewers are used to seeing a certain level of detail in the environmental review process. There is a certain degree of unease in making certain determinations in transportation planning when the level of detail is different or less than what is normally seen in project development.

- Buy-in that using corridor planning to inform NEPA is supported at the Federal level. Resource agencies need to understand that there is regulatory authority and policy support for this approach.

- Lack of documentation form planning. If decisions are not adequately documented, planning analyses and decisions may have to be revisited or redone in NEPA.

- Lack of understanding and communication between transportation planners and NEPA practitioners. An understanding of the goals, objectives, processes, and procedures of each other’s program areas will yield better coordination and process improvements.

What then to include in a corridor plan? Resource agencies would like to see transportation planners include...

- A description of the type, location, and severity of the environmental impacts and an understanding of the amount of time that has past since the planning study was conducted. Has there been a shift in state or local priorities since the planning study was originally done?

- Visuals and graphics, as in the Regional Outer Loop Study. GIS data files are helpful.

- The thought process underlying alternatives screening and analysis.

- Decisions commensurate with the level of detail of the analysis done as part of the planning study. For example, for the Regional Outer Loop Study, resource agencies would have difficulty evaluating specific alternative alignments since this would not be advisable considering the level of detail in the corridor study.

- A description of the information used as part of the planning study. For example, determining how current or complete the information that was used as inputs to planning analyses is essential in order to characterize the quality/reliability later in time.

- Analysis commensurate with the goals, scope, and scale of the planning study with regard to resource impacts. For example, in the Libby North Corridor Study, the level of detail allowed U.S. FWS to do a visual analysis of wetlands.

Documented public involvement; i.e., what public involvement was done, and was the public aware you were making decisions as a result of the planning study that would feed future NEPA processes.

Is there a way to simplify or clarify corridor planning in future guidance? What would the peers like to see?

- Guidance on when it makes sense to conduct a planning study as opposed to conducting a Tier One EIS. It would be helpful to get guidance or suggestions on the pros and cons of each approach.

- Guidance on mitigation banking or the appropriate way to address mitigation. Considering the potentially large cost savings, more effort should be focused on landscape, planning-scale mitigation.

- Guidance on methods to estimate other costs to consider as part of the planning study (e.g., right-of-way cost, mitigation cost, etc.) There is no consistent methodology for estimating costs at the planning level.

- Guidance on how to analyze indirect and cumulative effects at the planning level.

What is the best way to move this forward? FHWA should...

- Ensure that subsequent guidance is flexible enough to accommodate variation in project scales and standard practices and procedures at state DOTs and MPOs.

- Place an emphasis on environmental stewardship.

- Encourage agencies to do better planning work now in order to speed up the NEPA process later. Any guidance should recognize that good planning takes time, but has downstream benefits.

- Provide more assistance on what can and cannot be reasonably accomplished with a planning study.

back to table of contents

Conclusion

The Peer Exchange on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA shared numerous successes on the use of planning studies as a foundation for NEPA. The Parker Road Study showed the value of using a team approach to corridor planning, consisting of meeting face-to-face with resource agencies and developing a strong working relationship. Key to its success was the level of documentation, including the PEL matrix, statewide partnering agreement, and questionnaire. The I-83 Master Plan showed how innovative thinking in response to financial limitations could lead to a flexible vision of corridor improvements and phased implementation. NCTOG and EPA described a variety of technical tools being used for the Regional Outer Loop Study which could promote environmental stewardship in corridor planning. The study also illustrated the importance of leveraging existing groups in conducting outreach and communication with resource agencies (e.g., TRACES). ITD Region 6’s action team was successful because of its flexibility, continuous engagement with stakeholders, and its refusal to restrict itself to preconceived notions of what was possible in the corridor. Finally, the Libby North Corridor Study exemplified the successful use of the 2007 planning regulations. MDT’s project development process was more streamlined, less costly, and protective of the environment.

The peer exchange documented many lessons learned from the examples highlighted. CDOT felt that for PEL to work for future NEPA studies, indirect and cumulative impact analyses should be done. The Parker Road Study demonstrated that not all resource agencies have to be engaged the same way. Some resource agencies prefer to be involved later in the process or have varied interests and responsibilities. FHWA learned from the I-83 Master Plan that an in-depth safety review of a corridor should sometimes be done early. Both PennDOT and NCTOG learned that managing public expectations is a persistent challenge throughout a project. When agencies do early outreach, they naturally raise expectations. ITD learned that a candid approach to outreach and coordination sometimes leads to new, innovative solutions. Finally, MDT learned that making sure you have the right players at the table is an agency’s best first move.

Among recommendations for future guidance, participants at the peer exchange recommended that FHWA clarify when it makes sense to use planning to inform NEPA and more guidance on how to implement corridor studies successfully. FHWA should clearly identify what opportunities exist of r planning decisions that can used in NEPA, and identify the limitations of the approach. Future guidance should show the value of documentation and provide examples. It should also provide the pros and cons of conducting a planning study versus a tiered EIS. Guidance on ways to address mitigation and consider cumulative impacts at the corridor level also would be helpful. Finally, any guidance should recognize that change in practice takes time; flexibility is essential.

back to table of contents

Appendix A: Abbreviations

| AASHTO |

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

| CDOT |

Colorado Department of Transportation |

| CE |

Categorical Exclusion |

| CFR |

Code of Federal Regulations |

| DOT |

Department of Transportation |

| DRCOG |

Denver Regional Council of Governments |

| EIS |

Environmental Impact Statement |

| EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

| FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

| FWS |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

| IPWG |

Integrated Planning Work Group |

| ITD |

Idaho Transportation Department |

| LPC |

Locally Preferred Corridor |

| MDT |

Montana Department of Transportation |

| MPO |

Metropolitan Planning Organization |

| NCHRP |

National Cooperative Highway Research Program |

| NCTOG |

North Central Texas Council of Governments |

| NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act |

| NOI |

Notice of Intent |

| PEL |

Planning and Environmental Linkages |

| PennDOT |

Pennsylvania Department of Transportation |

| REAP |

Regional Ecological Assessment Protocol |

| SAFETEA-LU |

Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users |

| SH |

State Highway |

| SIU |

Sections of Independent Utility |

| TCS |

Tiering, Corridor, and Subarea Studies |

| TEA-21 |

Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century |

| TRACES |

Transportation Resource Agency Consultation Environmental Streamlining |

| TTC |

Trans-Texas Corridor |

| U.S.C. |

United States Code |

back to table of contents

Appendix B: Agenda

| Wednesday, December 2, 2009 |

| 8:30 – 8:40 |

Introductions and Background on Transportation Planning and Environmental Regulations |

Mike Culp (FHWA) |

| 8:40 – 8:50 |

Welcome from FHWA Deputy Administrator |

Gregory Nadeau (FHWA) |

| 8:50–9:00 |

Overview/Goals of the Peer Exchange |

Harrison Rue (ICF) |

| 9:00–9:15 |

Legal Perspective on Using Corridor Planning to Inform NEPA |

FHWA Office of Chief Counsel |

| 9:15–9:45 |

Presentation # 1: Parker Road Corridor Study |

Colorado Peers |

| 9:45–10:30 |

Facilitated Discussion |

All Participants |

| 10:30–10:45 |

Break |

| 10:45–11:15 |

Presentation # 2: I-83 Master Plan Study |

Pennsylvania Peers |

| 11:15–12:00 |

Facilitated Discussion and Recap of Morning Sessions |

All Participants |

| 12:00–1:00 |

Lunch |

| 1:00–1:30 |

Presentation # 3: Regional Outer Loop Corridor Feasibility Study |

Texas Peers |

| 1:30–2:15 |

Facilitated Discussion |

All Participants |

| 2:15–2:30 |

Break |

| 2:30–3:00 |

Presentation # 4: US-20 Ashton to Montana State Line |

Idaho Peers |

| 3:00–3:45 |

Facilitated Discussion |

All Participants |

| 3:45–4:15 |

Presentation # 5: Libby North Corridor Planning Study |

Montana Peers |

| 4:15–5:00 |

Facilitated Discussion and Recap of Day One |

All Participants |

| 5:00 p.m. |

Adjourn |

| Thursday, December 3, 2009 |

| 8:30–8:45 |

Welcome and Recap of Day One |

Mike Culp (FHWA) Harrison Rue (ICF) |

| 8:45–9:30 |

Planning Perspective on the Use of Pre-NEPA Studies

- Resulting Analysis and Decisions

- Reasonable Level of Detail

- Necessary Consultation and Opportunity for Review

|

All Participants |

| 9:30–10:15 |

Resource Agency Perspective on the Use of Planning Studies to Prepare for NEPA

- What Should be Included

- Opportunity to Comment

- Level of Documentation

|

All Participants |

| 10:15–10:30 |

Break |

| 10:30–11:45 |

Roundtable Discussion

- Other Examples (Opportunity for Webinar/ Conference Call Participants to Weigh In)

- Common Challenges and Opportunities

- Recommendations for Future Activities

|

All Participants |

| 11:45–12:00 |

Closing Remarks |

Mike Culp (FHWA) |

| 12:00 p.m. |

Adjourn |

back to table of contents

Appendix C: Participants

Attending In-Person

Attending Remotely

back to table of contents

Footnotes

1 National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), 42 U.S.C. § 4321 et seq.

2 Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU)

3 AASHTO Practitioner’s Handbook. Using the Transportation Planning Process to Support the NEPA Process. February 2008.

4 Federal Highway Administration 23 CFR Parts 450 and 500; Federal Transit Administration 49 CFR Part 613.

5 https://pubsindex.trb.org/view.aspx?id=639918

6 23 CFR Section 450.212(a), 450.318(a).

7 https://itd.idaho.gov/pop/assets/AppPDF/5069.pdf

8 https://itd.idaho.gov/pop/ITDPOP_2.html

9 Highway 567 lies outside the Grizzly Bear Recovery Zone, but within an area regularly occupied by grizzly bears.

back to table of contents