Interim Guidance on the Application of Travel and Land Use Forecasting in NEPA

Federal Highway Administration, March 2010

- Executive Summary

- 1.0 Background

- 1.1 Rationale and Need for Guidance

- 1.2 Process for Developing Guidance

- 1.3 Using the Guidance

- 1.4 Evolving Forecasting Methods

- 2.0 Guidance

- 2.1 Project Conditions and Forecasting Needs

- 2.1.1 Conceptual Review of Anticipated Analysis

- 2.1.2 Establishment of Forecasting Analysis Requirements

- 2.1.3 Consideration of Tools Required to Forecast Needs

- 2.1.4 Review of Prior Forecasts and Technical Issues

- 2.1.5 Incorporating Analyses Done in Transportation Planning Studies

- 2.1.6 Documentation of Project Conditions and Forecasting Needs

- 2.2 Suitability of Modeling Methods, Tools, and Underlying Data

- 2.2.1 Age of Forecasts, Models, Data, and Methods

- 2.2.2 Calibration, Validation, and Reasonableness Checking of Travel Models

- 2.2.3 Calibration, Validation, and Reasonableness Checking of Land Use Forecasts

- 2.2.4 Policy Evaluation Considerations

- 2.2.5 Advancing Technologies and Methods

- 2.2.6 Consideration of Peer Review

- 2.2.7 Documentation of Suitability of Modeling Methods, Tools, and Underlying Data

- 2.3 Scoping and Collaboration on Methodologies

- 2.3.1 Reaching Consensus on Forecasting Methodologies

- 2.3.2 Documentation of Scoping and Interaction with Other Agencies

- 2.4 Forecasting in Alternatives Analysis

- 2.4.1 Overview of Transportation-related Effects and Impacts

- 2.4.2 Objective Application of Forecasting Data and Methods

- 2.4.3 Refinement of the Analysis during Screening

- 2.4.4 Development of Forecast Confidence

- 2.4.5 Moving from Regional Model Output to a Project Level Forecast

- 2.4.6 Addressing Land Development or Redistribution Effects

- 2.4.7 Documentation of Forecasting in Alternatives Analysis

- 2.5 Project Management Considerations

- 2.5.1 Potential for Reevaluating Analysis

- 2.5.2 Consistency

- 2.5.3 Enhanced Communication between

NEPA Study Team and Forecasting Practitioners

- 2.5.4 Considerations for Developing Scopes of Work for Forecasting Practitioners

- 2.6 Forecasting for Noise and Air Emissions Analyses

- 2.6.1 Noise Analysis

- 2.6.2 Air Quality Emissions Analyses

- 2.7 Documenting and Archiving Forecast

Analyses

- 2.7.1 Documenting Forecast Analyses

- 2.7.2 Archiving Forecast Analyses

- 3.0 Conclusion

- 4.0 Appendices

- 4.1 Case Law Summary (January 2009)

- 4.1.1 Introduction

- 4.1.2 Standard of Review

- 4.1.3 Travel and Land Use Forecasts: When Are They Relevant?

- 4.1.4 Issues Affecting Sufficiency Under NEPA

- 4.1.5 Linking Planning and NEPA

- 4.2 Definitions

Travel and land use forecasting is critical to project development and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) processes. In light of the importance of forecasting, the high variation in

practice, and the litigation risk involved, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) created this guidance to encourage improvement in how project-level forecasting is applied in the context of the NEPA process. While technical guidelines for producing forecasts for projects have been documented by others, little has been published on the procedural or process considerations in forecasting. This guidance attempts to fill that gap. The primary audiences are NEPA project managers, FHWA staff, forecasting groups at Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and State Departments of Transportation (DOTs), as well as consultants that support MPOs and DOTs in conducting corridor and NEPA studies. Following this guidance is strictly voluntary. It is based on lessons learned and best practices and does not constitute the establishment of an FHWA standard. Not all studies are the same; therefore this guidance is intended to be non-prescriptive, and its application flexible and scalable to the type and complexity of the travel analysis to be undertaken.

This guidance document identifies seven key considerations:

- Assess project conditions and scope the forecasting needs of the study: It is crucial to scope the forecasting effort to meet the project analysis, decision-maker and stakeholder needs in the study area. For this reason it is useful to begin the forecasting process by understanding the requirements of the study and anticipating decision-maker and stakeholder interests with respect to forecasting.

- Review the suitability of modeling methods, tools, and underlying data: It is important that the study team review the suitability of available modeling methods and the underlying data, including consideration of the currency and quality of the model data and methods, and that they analyze the data and methods’ ability to adequately examine alternatives.

- Conduct scoping and collaborate on methodologies: Scoping is a collaborative process involving the lead agencies, resource and regulatory agencies, and the public and is typically how a NEPA study begins. It is critical for the study team to document the broad agreements reached during scoping on the assumptions to be used for the land use and travel forecasting.

- Objective application of forecasting in alternatives analysis: The requirement for the alternatives analysis to be an objective evaluation makes it essential for the study team to apply forecasting data and methods objectively without any bias towards a particular alternative. Important considerations include understanding uncertainty in assumptions and forecasts and how induced demand and land development effects are taken into account.

- Project management considerations: NEPA studies are often complex undertakings and may be accompanied by various special considerations that warrant extra attention, such as the potential for re-do analysis loops and ensuring documentation consistency.

- Forecasting for noise and air emissions analyses: Land use and travel demand forecasting models are used to provide inputs to noise and air quality assessments. It is important that assumptions that are made in general forecasting applications as part of the NEPA study are consistent with those used in the noise and air quality analyses.

- Documentation and archiving: It is important for NEPA documentation to include enough technical detail to explain complex information in an understandable manner, and to describe how analytical methods were chosen, what assumptions were made, and who made those choices.

As a companion to this guidance, the FHWA is creating a document that will include case studies and best practices to help further the improvement of forecasting techniques at the project level. Training and technical assistance will also be made available to provide educational and peer exchange opportunities to State DOTs, MPOs, resource agencies, and the consultant community, to encourage needed dialogue and discussion to improve the state-of-the-practice.

Back to Top

Travel and land use forecasting is critical to project development and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) processes. Forecasts provide important information to project managers and decision-makers, and provide foundations for determining purpose and need. They are essential in evaluating: the performance of alternatives; the estimation of environmental impacts such as noise and safety (based on traffic volume or exposure) and emissions (based on traffic volume and speed); induced land development effects (change in land development patterns due to changes in accessibility); and resulting indirect and/or cumulative effects (such as watershed effects). In short, travel and land use forecasting is integral to a wide array of corridor and NEPA impact assessments and analyses.

Forecasting methodologies and their applications are often a source of significant disagreement among agencies and interest groups, and are frequently the focus of project-level litigation. While many of the issues raised are technical and methodological, often they are process-related or procedural in nature: misunderstandings regarding what work was done, what assumptions were made or input used, how the methods and approaches were chosen, and how the procedures were carried out. Forecasting is not a heavily legislated or regulated area of science, and is thus mainly driven by professional practice. This situation makes assessments of standards of practice difficult, and results in a large variation in practice and experience among transportation and resource agencies and consultants.

In light of the importance of forecasting in project development and NEPA, the high variation in practice, and the litigation risk involved, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) created this guidance to encourage improvement in the state-of-the-practice in relation to how project-level forecasting is applied in the context of the NEPA process. While technical guidelines for producing forecasts for projects have been documented by others,[1] little has been published on the procedural or process considerations in forecasting (how to apply forecasting in the context of NEPA). This guidance attempts to fill that gap.

In 2007, the FHWA initiated a project to provide practitioners and stakeholders with process and procedural guidance on how to apply forecasting in the context of project development and NEPA studies. The project was scoped to include:

- Creation of an FHWA expert panel, consisting of modeling, NEPA, and planning experts to advise the project

- Outreach to stakeholders and interest groups

- Formulation of project development and NEPA guidance and a review of relevant case law

- Development of a guidebook to include case studies and best practice examples

- Creation of training materials and technical assistance

Early in 2008, the FHWA expert panel was assembled to discuss and provide advice on the purpose and format of the guidance, and how to move forward on supporting activities. The panel included active participation by FHWA headquarters and field offices. The panel provided invaluable input to the guidance development process. In addition, during 2008 and 2009, the FHWA Office of Chief Counsel developed a case law summary that related forecasting issues and the NEPA process; this was also used to inform the guidance. Information on the project was provided to stakeholder and interest groups at various national meetings and venues.

This guidance is intended to provide assistance to NEPA and forecasting practitioners on improving how forecasting is used and applied in the project development and NEPA processes. It does not examine the details of how to calibrate and validate models; rather, it provides procedural and process considerations in developing forecasts in NEPA studies. The primary audiences are NEPA project managers, FHWA staff, forecasting groups at Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and State Departments of Transportation (DOTs), as well as consultants that support MPOs and DOTs in conducting corridor and NEPA studies.

Following this guidance is strictly voluntary,[2] and it is suggested that it be adjusted to the individual planning and project contexts, and the scale, size and capabilities of the project and the lead agencies. The guidance is based on lessons learned and best practices and does not constitute the establishment of an FHWA standard. Not all studies are the same; therefore this guidance is intended to be non-prescriptive, and its application flexible and scalable to the type and complexity of the travel analysis to be undertaken.

It is also intended that this guidance will improve communication between forecasters and NEPA practitioners. Travel and land use forecasters are encouraged to demonstrate and explain the validity of the forecasting process along with the reasonableness of the forecasts as a way to mitigate litigation risk. Significant efforts were made to consider relevant case law in the creation of the guidance and, where applicable, specific cases are cited. Hopefully, applying this guidance will assist agencies in creating better and more legally defensible forecasting applications.

The state-of-the-art and the state-of-the-practice in travel forecasting are always evolving, and the practice typically changes based on careful consideration of the potential or known benefits and costs of different approaches. While this guidance outlines important considerations in developing and documenting forecasts, the intent is not to advocate specific technical model design elements or models to produce forecasts. Because the practice is constantly evolving, forecasting methods are evaluated based on what peers are successfully doing with a reasonable effort.[3]

Travel forecasting methods are evolving because of: (1) advancements in software and hardware; (2) improved data collection methods; (3) a need for improved approaches for analyzing the wide array of transportation-related policies, pricing initiatives, and investments; and (4) the evolution of planning and project development processes and regulations. Each of these factors was considered when this guidance was drafted.

Clearly, it is very important that the methods utilized to produce forecasts are defensible and that the forecasts are reasonable. The specific methods used to produce forecasts can and do vary widely based on the timeframe for the study, and the defensibility of the methods must be judged based on the needs of the study. While certain aspects of models and approaches to forecasting are relatively common, well understood, and accepted, it can often be difficult to judge the merits, costs, and schedule considerations of one modeling approach over another. Additionally, it is not always the case that more difficult or costly modeling methods produce the best forecasts. One motivation for this guidance is to present a framework for considering these challenges in the context of a NEPA study where the forecasts may be questioned and the methods used to produce forecasts will be reviewed and compared to applications elsewhere.

Back to Top

This guidance document is organized around seven key considerations: (1) the project conditions and forecasting needs of the study; (2) the suitability of modeling methods, tools, and underlying data; (3) scoping and collaboration on methodologies; (4) forecasting in the alternatives analysis; (5) project management considerations; (6) forecasting for noise and air emissions analyses; and (7) documentation and archiving.

It is crucial to scope the forecasting effort to meet the project analysis, decision-maker and stakeholder needs in the study area. For this reason it is useful to begin the forecasting process by understanding the requirements of the study and anticipating decision-maker and stakeholder interests with respect to forecasting.

Far too often, the forecasting process is not given enough thoughtful proactive attention, and it is not scoped in a detailed manner that will minimize or account for potential issues or problems. It is common for one of the first exercises to be the production of a no-build forecast, with little consideration given to the credibility of and the assumptions made in the forecast. If, instead, the NEPA study team[4] determines the appropriate level of the forecasting effort at the outset and begins by ensuring the suitability of the tools, then the NEPA process can proceed more reasonably.

The NEPA lead agencies often define the study area while also developing the purpose and need statement. They typically base the boundary of the study area on the logical geographic termini, the project purpose and need, and the expected limits of potential impacts. It is important that the study area be large enough to encompass the range of alternatives that will be developed to meet the project purpose and need. The area within which transportation impacts can be measured will likely be substantially larger than the area within which direct environmental impacts are measured. It is important to ensure that the forecasting is extensive enough in its geographic reach to reasonably estimate the transportation and land development impacts.

An early assessment of the current and anticipated travel demand in the study area is important to the success of both the NEPA process and the forecasting effort. It is helpful to document what is understood about the existing travel demand and growth potential in the corridor or area being evaluated. For example:

- What is the nature of demand in the corridor in terms of trucks versus passenger cars, through versus local trips, or non-discretionary trips (such as commute to work) versus discretionary trips (such as shopping trips)?

- Are there unique major generators in the corridor?

- What magnitude of growth in travel demand is anticipated?

- To what extent is the need for the project based on today’s travel conditions versus anticipation of growth?

Answers to these questions, as well as others, can inform data collection and help assess the suitability of the forecasting models.

Once the lead agencies have considered the anticipated study needs, it is important to establish the travel forecasting requirements for the study. The principal forecasting analysis requirements to be defined early in the process include:

- Specifying the analysis years

- Identifying the geographic scope of the transportation and land development analysis

- Considering the level of detail required in the analysis

- Outlining an initial list of what travel and land use-related or -dependent impacts are to be estimated (see section 2.4.1 on direct, indirect, and cumulative impacts).

2.1.2.1 Identifying Analysis Years

Selecting the appropriate timeframes for analysis is essential. Forecasters typically use a 20- to 30-year horizon for long-range transportation planning purposes. In addition to a base year and a future forecast year, intermediate forecast years are usually considered, including (most notably) the opening date of the project. It is common for these intermediate forecast years to be chosen to correspond to future planning horizons already examined in the region or State’s long-range plan since modeling inputs, such as land use forecasts, for these years are readily available. Table 1 presents a list of possible analysis years.

Table 1: Possible analysis years for travel forecasting

|

Base Years

|

Base model year

|

The calibration year for the travel model

|

Base project year |

This could be different from the base model year; it is an updated base year that is validated and is as close as possible to the current year

|

|

Forecast Years

|

Open-to-traffic year

|

Expected future year that the project will open; in the case of phased projects this might be a sequence of intermediate forecast years

|

|

Plan horizon year

|

A future forecast year that often corresponds with the long-range plan horizon

|

|

Design year

|

An alternative future forecast year for the project that may be earlier or further into the future than the forecast year

|

The appropriate base and future analysis years for a particular study may not align with the available analysis years, which may lead the study team to update the travel model’s base year and/or create new land use and travel forecasts for NEPA analysis. Two common examples of this situation are:

- The travel model’s base year is several years ago and travel demand in the study area has changed. A more recent base year, as close to the current year as possible, is needed so that the travel model adequately represents current travel demand in the study area.

- The planning horizon year is different from the design year of the project. For example, the planning horizon is 25 years in the future and the design year of the project is 30 years.

Similarly, air quality or noise analysis requirements are a consideration; for example, when a hot-spot or noise analysis is needed this may require the selection of a unique analysis year(s) for that work.[5]

It is important for assumptions regarding open-to-traffic years to be explicit and discussed in the documentation. Also, a project might not rely on future performance to meet purpose and need, and its "design year" may be shorter, or the project is designed to manage current congestion. In that case, while forecasts could be required for potential impacts, forecasting to support purpose and need is less essential.

Phasing and sequencing considerations are also crucial when the study team is establishing forecasting analysis requirements. If an alternative will be implemented over time, or if alternatives could be implemented with phases in different sequences (for example the sections of a new highway may be built in phases as travel demand increases over time) then it is important for these assumptions to be discussed in the documentation as they will lead to particular analysis needs, such as intermediate analysis years and additional road network and land use assumptions.

2.1.2.2 Geographic Scope of Analysis

It is important to ensure that the forecasting is extensive enough in its geographic reach to estimate travel behavior, transportation, and land development effects.[6] Unique issues may arise when applying a model to evaluate a project near a model boundary. In such cases, model refinements may be needed. In these boundary conditions the traffic analysis zones (TAZs) are typically large, the coded road network is sparse, and travel patterns are heavily affected by external demand. Taken together, these issues lead to both less detail and less model sensitivity. If the project is proximate to the boundary of the model area, it is suggested that the study team code a more detailed road network. It is also suggested that the study team consider both adding more detail to the TAZ structure and expansion of the model to extend its boundary. Refining or expanding the model may lead to significant efforts such as the collection of additional land use data and the need to forecast land use changes for that area, the need to do additional model validation, or, in the case of expanding the model, the integration of land use data and forecasts from a different planning jurisdiction.

2.1.2.3 Level of Detail Required in the Analysis

Using a variety of methods, one can produce forecasts and output indicators at a regional scale (e.g., regional vehicle miles traveled, or VMT), at a microscopic scale (e.g., intersection turning movements), and at a corridor scale (e.g., difference in roadway volumes under two scenarios).[7] It is important for the lead agencies to determine the appropriate level of detail for forecasting analysis based on the specifics of the study, including considerations related to the stage of the project development process and stakeholder issues. It is suggested that performance measures reflect non-automobile impacts, such as transit use. It is important for the lead agencies to select the performance measures so that the impacts of each alternative can be fully explained in the NEPA documentation. It is also important to select the performance measures that can illustrate the relative merits of each alternative in the context of the project purpose and need.

The project development process can be long, with varying levels of forecasting detail typically necessary at different stages in the process; it is essential to avoid confusing detail with accuracy. Because more detail tends to require more time and effort, it is generally advised to begin a study focusing on more aggregated and large-scale impacts, particularly when the possible alternatives are numerous (pre-screening) or forecasting methods are being refined. Different forecasting tools and processes allow for analysis at different geographic scales; it is important for the study team to judge and explain which modeling tools are appropriate for which analyses and also to recognize the level of detail required at each stage in the study. Forecasting is an iterative process, and with iteration generally comes more confidence and ability to add detail to better inform complex decisions.

It is suggested that the lead agencies prepare a brief history describing the tools that have been used to make forecasts in the corridor and region. Once the available data and models have been reviewed, it is important for the study team to consider what data and tools are appropriate for the analyses. Depending on the needs of the study, this can include consideration of readily available data and models, as well as supplementing what is available. As the study team considers applying current models to evaluate the increasingly complex strategies and policies of interest in the project area, it is important to assess the limitations and sensitivity of those models. By identifying the significant issues related to alternatives to be considered, such as pricing, high-occupancy vehicles (HOVs), transit, and transportation control measures, the study team can ensure that methodology and analysis decisions are made with these factors in mind.

In many areas where land use and travel demand models are frequently used in planning and project development, multiple users may exist. For example, modeling staff within the MPO or DOT may be undertaking modifications to the land use or travel model as part of an ongoing model improvement process. In addition, consultants working on other studies in the region may be incorporating additional model functionality and/or correcting existing model errors and deficiencies. It is therefore critically important that the study team consider modeling tools under development, or ones that might be developed in the short term, for inclusion in the land use and travel forecasting process, especially when an improvement to the model would directly affect the project being studied. This is particularly true when the study team expects the project development process to be relatively long or complicated. See section 2.2.1 for additional discussion of these issues.

Before producing new forecasts, it is useful to critically review past efforts to be aware of the prior work and to improve on or complement that work. In its review of prior planning studies and prior NEPA studies either for the current study project or other projects in or close to the same study area, it is important for the study team to consider travel and land use forecasting needs, in terms of both the forecasts themselves and any known technical concerns related to forecasting. In many cases, projects have been in the planning phase for 10, 20, or more years, and transportation plans identify specific alternatives. To some degree, past decisions are supported by these prior analyses. Therefore, it is critical to assess the comprehensiveness and usefulness of past analyses and compare new analyses and forecasts to previously documented forecasts. In some cases, lead agencies in NEPA may choose to directly use previously developed forecasts. It is recommended that this decision be taken with some care, as previously developed forecasts may not have been subject to the same rigorous review that forecasts produced as part of a NEPA study are likely to face. See section 2.1.5 below for more detail.

To the extent that prior litigation has raised issues related to land use and travel forecasting in the project’s region or identified issues in the corridor germane to forecasting, it is important to ensure that these issues are fully addressed or that prior responses are understood and reconsidered. It is important for the study team to describe and clearly and completely address both past judgments in cases pertaining to the project and any ongoing litigation. It is also important to consider and adequately address the less obvious cases that have stalled or stopped planning and project development efforts in other regions with relevance to the subject project. Remedying the concerns raised by legal findings and opinions may lead to significant changes in the team’s approach to the analysis for the study.

Often, forecasts are prepared for a project or corridor prior to the beginning of the NEPA process. Forecasting may have been done as part of system-level planning activities, or as part of corridor, feasibility, or sub-area studies. At the system level, major efforts include defining the transportation problem, and developing and testing potential solutions. Many times these problems and potential solutions are identified and tested during planning because that is the scale at which they are appropriately analyzed. For example, developing system-level land development estimates is best done at a regional level, where systemic interactions between transportation and land use policies and the characteristics of existing land availability and transportation accessibility can be analyzed. Travel and land use forecasting procedures play a central role in these analyses.

Corridor, feasibility, and sub-area studies done in a transportation planning context are not as detailed as analyses performed for project-level NEPA alternatives analysis, but are often conducted to refine purpose and need in a corridor, to screen out unreasonable alternatives, and to preliminarily evaluate potential impacts of alternatives, including travel and land development effects. Again, forecasting is critical to performing these studies. All too often, these analyses are redone in the NEPA process, resulting in duplication of effort. This situation also can result in potentially undermining past analyses, and discounting public and agency involvement in the prior studies.

Recognizing these issues, the FHWA and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) have worked over the past decade to improve the ability of agencies to utilize analyses done as part of planning studies in the NEPA process. Typically referred to as “linking planning and NEPA,” these efforts have culminated in a revision to 23 CFR Part 450 (the FHWA and FTA regulations for the Statewide and metropolitan transportation planning process), and 23 CFR Part 771 (FHWA and FTA NEPA implementing regulations).[8] These regulatory provisions represent new authority to the FHWA, FTA, State DOTs, and MPOs to use decisions and analyses conducted in transportation planning to be used in the NEPA process. Since forecasting is so central to planning studies and analyses, the methods and results can be incorporated by reference in the NEPA process. Such analyses or results should be made available during the NEPA scoping process.

However, the regulatory authority discussed above does not come without conditions.[9] The NEPA lead agencies determine the applicability and appropriateness of the methods used and the continued validity of the results before they can be used on a specific NEPA study or project. The studies must have contained a reasonable opportunity for public review and comment, must be adequately documented, and must have had appropriate interagency involvement in the efforts. From a forecasting perspective, the technical documentation must be adequate to explain and defend those decisions in the context of NEPA. Also, early public and interagency involvement in the forecasting efforts for the planning studies is essential as it helps build trust and comfort with how these analyses were performed, and increases the comfort level in using these forecasts in the NEPA process.[10]

This section of the guidance has discussed the importance of beginning the analysis effort with a careful review of forecasting needs. To ensure that the findings of this review are retained and can be referred to as the analysis progresses, it is important for the study team to produce documentation of this work. A possible structure for the documentation follows.

- Conceptual review of anticipated analysis

- Establishment of forecasting analysis requirements

- Identifying analysis years

- Geographic scope of analysis

- Level of detail required in the analysis

- Consideration of tools required to forecast needs

- Review of prior forecasts and technical concerns

- Incorporating analyses done in transportation planning studies

A key purpose of this documentation is to demonstrate that these issues have been considered by the study team. In addition to documenting the decisions that were reached regarding technical issues such as selection of analysis years, such documentation can demonstrate the process and rationale used to make the decision, the information considered in the decision-making process, and who was involved in the decision-making process.[11]

Back to Top

Once the conditions and forecasting needs of the study have been assessed, including a consideration of the forecasting tools and requirements, it is suggested that the study team review the suitability of available modeling methods and the underlying data. For this, it is important for the study team to both consider the currency and quality of the model data and methods and analyze the data and methods’ ability to adequately examine alternatives. The purpose of FHWA guidance on travel models and other published resources[12] is to promote good practice. Good practice in model development and application has positive consequences in project development.

It is important for the study team to establish how current the land use forecasts, travel demand model, data, and methods are before the alternatives can be analyzed. This process may begin with identifying whether the land use forecasts and the travel demand model are the current versions adopted by the MPO or DOT and whether the methods proposed for the analysis conform to current Federal, State and local requirements, as applicable. Section 2.5.2 explains that it is also important for the study team to identify which methods are being used by concurrent NEPA studies in the same region. However, requesting and receiving the latest land use forecasts and the travel demand model available from the MPO or DOT is only the first step. It may be advisable to update certain elements of the land use forecasts, travel demand model, or model data if they are based on data that were collected a significant time prior to the study. For example, trip generation rates based on survey data collected 20 years before the study may need to be updated. It is important that the study team ensures that the data reflect the most up-to-date assumptions about the relevant transportation infrastructure and land use and socioeconomic conditions. However, there is a limit to the scope of updates to forecasts, models, and data that are required as part of the analysis for a NEPA study. If the costs for updating tools and collecting data would be “exorbitant” then 40 CFR § 1502.22 (b) may apply. It is important to document decisions regarding model updates and also why the decisions were made.

If the study team refines a land use forecast, a travel demand model, or their inputs, it is critical that the study team knows which forecast and model version are being used and, if necessary, institute a system to track and manage the versions of forecast and model tools and inputs. It is important to do more than simply state that “the model” was used to generate travel forecasts. Because the travel demand model and land use forecasts for a particular region may often be in flux (as discussed in section 2.1.3), it is recommended that the study team use the most recently adopted version of the land use forecasts and the travel demand model. Although forecast and model refinements between versions may be few and unrelated to questions pertaining to the study, it is possible that the differences in results produced by a “Version 2.2” versus a “Version 2.3” could be substantial.

An MPO or DOT will not typically adopt a new version of a travel demand model until it has been validated and the results checked for reasonableness, although the thoroughness of these checks varies. It is important to keep in mind that a version of a travel model is made up of both the model code and the various model inputs, such as land use forecasts. Therefore, it is necessary to confirm that the proper model code is being used with the corresponding set of model inputs that together represent the current adopted version of the model.

During the course of a study, an MPO or DOT may adopt a new land use forecast or a new version of the travel demand model. In this situation, it is important for the study team to consider the implications of changing their analysis approach to use the newly adopted forecast or model; section 2.5.1 on consideration of the potential for re-do analysis loops discusses this issue.

The calibration, validation, and reasonableness checking of travel models constitute an important and necessary sequence of steps that are taken to prepare a travel model for making reasonable forecasts.

- Calibration, where adjustments are made to the model so that current observed conditions in the study area are reasonably reproduced, ensures that the travel model’s forecasts are built on a foundation that is a good representation of existing travel characteristics.

- Validation, where the sensitivity of the model to changes in inputs and assumptions is tested, ensures that the travel model responds reasonably to transportation system changes and will have the ability to produce forecasts.

- Reasonableness checks are additional tests of a model’s forecasting performance, including evaluating the travel model in terms of acceptable levels of error and its ability to perform according to theoretical and logical expectations. The checks help to ensure that the model tells a coherent story about travel behavior.

Forecasts from appropriately calibrated and validated models are likely to be more useful throughout a study and raise fewer questions. It is important to demonstrate that the modeling methods proposed for the study corridor have a strong foundation in observed data, are able to represent change, and credibly compare alternatives in a forecasting setting. The calibration and validation of travel models provide the best evidence that the models adequately represent the transportation system supply characteristics and traveler behaviors that are crucial to subsequent forecasts for NEPA studies. Consequently, the lead agencies have a substantial interest in exerting appropriate efforts to calibrate and validate models.

In the context of a NEPA study, it is important for the study team to focus any calibration and validation efforts that they undertake on the study area. Typically, a regional travel demand model will have been adequately calibrated and validated at least at a regional level prior to adoption. While it is important for the study team to critically review the documentation of this effort, it is suggested that more emphasis be placed on checks at the study area level.

It is suggested that the study team scale their calibration and validation effort according to the scale of the analysis, such as its geographic scope. For example, studies that involve the analysis of major changes to transportation system supply with impacts across a large study area require a much broader calibration and validation effort than a simpler project with a smaller study area.

There are several published sources[13] documenting useful calibration and validation checks, and the key elements of a comprehensive review are outlined below.

Calibration - A meaningful calibration effort would include:

- Review of trip generation particularly at key generators in the study area

- Detailed inspection of modeled origin–destination patterns in the study area to demonstrate that they compare closely to observed travel within and through the study area

- Careful comparison of point-to-point travel times or speeds on individual road segments, to demonstrate that the model responds appropriately to changing traffic volumes

- Comparison of modeled traffic volumes with traffic counts both for individual roadway segments and at more aggregate levels such as throughout the study area

- Network checks to identify coding errors in, for example, posted speeds and capacities.

Figure 1[14] shows the possible effect of compounding error in travel models, where each step in the modeling process increases the overall error. This underscores the importance of identifying sources of error in each element of the travel model. Implementing a calibration effort such as described above is aimed at minimizing error in each step in the modeling process.

Figure 1: Effects of compounding error in model validation

Validation and Reasonableness Checking – It is important for the study team to conduct validation of the travel model at a level of detail that supports reliable forecasts and output indicators, focusing on the ability of the model to represent the effects of transportation system changes. This suggests validation of the travel markets deemed important in the study corridor by analyzing, for example, their trip generation, geographic distribution of trips, traffic volumes, and travel speeds.

The validation effort involves reviewing forecasting results, and results of sensitivity tests, to evaluate the credibility of the changes produced by the model. Sensitivity tests check the responsiveness of the travel forecasting tool to changes in the transportation system, socioeconomic data, and transportation policies. Often, sensitivity is expressed as the elasticity of an independent variable. For example, modelers can express a travel model’s sensitivity to the effects of a parking rate increase in an area by relating the increase in parking prices to the reduction in demand for travel to that area.

Reasonableness checks include the comparison of input such as rates and parameters, outputs such as total regional values, values for subregions covered by the model, and logic tests. Model parameters can be checked for consistency against observed values, parameters estimated in other regions, or secondary data sources. A model can be evaluated in terms of acceptable levels of error, its ability to perform according to theoretical and logical expectations, and the consistency of model results with the assumptions used to generate them.

There are several useful types of validation and reasonableness checks, including the following:

- Forecasting buildup to understand how the different model inputs contribute to changes from the base year to the forecasting year. It is useful to isolate and understand changes in travel patterns and congestion in a corridor that are due to land use growth versus transportation system expansion. Other inputs that may be important in a corridor include assumptions related to external trips and special generators. This series of tests could easily be conducted using the long-range transportation plan model inputs. Section 2.4.2 discusses the importance of the study team explicitly defining and documenting the future no-build highway (and transit) networks. Understanding the impact of planned changes to the transportation system is an important element of the forecasting buildup.

- Interpretation of the story told by the models themselves about the behavior of travelers. This test helps to ensure that the various parameters, assumptions, network coding conventions, and other decision rules in the models tell a coherent story about travel behavior. This helps prevent (by highlighting the need for correction) implausible relationships and explains the properties of the models to non-travel forecasters.

- Demonstration of reasonable predictions of change between today and the future as well as in response to changes in the transportation system. This last set of tests adds a major new dimension to the understanding of the properties of a new model set: the ability to respond reasonably to demographic growth and consequent changes in congestion, and to produce coherent responses to major changes in the transportation network.

Land use forecasts are one of the foundations upon which travel demand forecasts are built and, as such, it is important for the study team to invest effort in reviewing and checking both base year land use for accuracy and future year land use forecasts for reasonableness, and to understand the implications of growth on the transportation forecasts. A range of land use forecasting techniques may be used during a study from more qualitative techniques such as expert panels to quantitative techniques utilizing land use models. At the simplest level, it is important to understand how much of the justification for a project is based on current demand versus future growth and the implications of these findings related to the uncertainty in the forecasts; at a more complex level, where the study team’s analysis involves more complex land use analysis tools and models, a process akin to the calibration and validation of the travel model described above may be necessary.

As discussed in the context of reviewing the travel demand model, it is suggested that the study team scale their land use review effort according to the scale of the analysis, such as its geographic scope and potential for land development or redistribution effects. Section 2.4.6 discusses in detail considerations for addressing land development or redistribution effects in the preparation of project level forecasts.

A review of the base year land use in the study area will often be undertaken as the first step of travel demand model calibration and validation checks. Published sources[15] discuss recommended approaches to check base year land use and socioeconomic data, and also explain the importance of checking these input data to reduce the level of effort needed to perform other validation steps; indeed, it is critical as errors in these data propagate through the subsequent steps in the model system (as shown in Figure 1). In addition, errors that appear unimportant at a regional level may increase in significance as they are proportionally more important at a study area level.

The complexity of the review of the land use forecasts will depend on the approach selected for land use forecasting. A general framework for producing land use forecasts is as follows:[16]

- Understand existing conditions and trends: This principally involves assembling data that will be necessary to conduct the analysis.

- Establish policy assumptions: This step involves determining currently anticipated changes in regulatory or economic policies such as zoning, environmental regulations, and impact fees.

- Estimate regional population and employment growth resulting from change in accessibility: This step uses local population and employment trends; broader State and national economic industry trends; and economic forecasting models.

- Inventory land with development potential: This step identifies undeveloped and underdeveloped land and, in combination with environmental restrictions and zoning regulations, quantifies land available to absorb growth.

- Assign population and employment to specific locations: This step uses land availability, the cost of development, and the attractiveness of various areas to estimate the amount and type of growth that will occur in each zone.

The approaches used in this process vary from qualitative techniques (such as utilizing an expert panel and/or the Delphi process) to quantitative models to forecast regional population and employment changes (such as regional economic impact models) to land use models that are integrated with travel demand models.

For project level analysis in cases where alternative specific land development effects are not expected, it is common for the study team to review adopted regional level land use forecasts or use an integrated land use and travel demand model that has been calibrated at a regional level, rather than producing new forecasts. It is important that the study team reviews and understands how each of the steps in the forecast framework was undertaken and how each step applies to the land in the study area. This review might include checks of:

- Whether regional level trends used to produce forecasts have been reflected historically in the study area

- The accuracy of the land inventory (such as the amount of vacant land) for the study area

- Pending development/redevelopment proposals, particularly those that will exceed regulatory limits on density or other factors

- The reasonableness and feasibility of the resulting development allocations to the study area.

Consultation with local governments and others with knowledge of land development patterns can enhance this process.

A critical element of this review is for the study team to understand the future transportation network assumed in the land use forecasts, and particularly whether any of the alternatives under consideration are included in the transportation network assumed in the land use forecasts (see Section 2.4.2).

Forecasting models have been widely used to estimate the effects of standard roadway capacity improvements, like road widening or the addition of a new road. While these types of forecasting efforts can still be complicated and the models may need refinement to be useful, models are built with the basic intention of modeling roadway and major transit capacity improvements. Increasingly, however, requests are being made to assess the impacts of transportation demand and supply policies that models were not designed for when they were originally constructed. For example, alternatives in a study may include ramp metering to better manage flow on limited access facilities, a transit technology not currently existing in the region, or various pricing strategies. While some models are equipped to assess these policies, many that are routinely applied in current studies are not. Determining the extent to which some of these policies will be major components of a NEPA study will help ascertain the amount of effort it may require to test alternatives and model changes and/or adjustments that may be needed.

2.2.4.1 Evaluating Transportation System Management/Transportation Demand Management Strategies

Transportation system management (TSM) strategies, or intelligent transportation system (ITS) strategies, are put in place to reduce both recurring congestion and incident-related congestion. To the extent TSM strategies affect recurring congestion, the FHWA recommends that they be represented in road or transit networks as capacity improvements relative to facilities without these improvements. Additionally, ITS technologies are increasingly being implemented to monitor and collect travel data (e.g., speeds and volumes) and in this respect are valuable sources of model calibration and reasonableness checking data that can be used to assess capacities, free-flow and congested speeds, volumes by time of day, and the relationship between speed and volume.

Transportation demand management (TDM) strategies vary widely and are designed typically to discourage single-occupant vehicle use during peak hours. These include, but are not limited to, changes in parking policies, ride-sharing, employer-subsidized transit passes or van pools, policies allowing flexible work schedules and telecommuting, HOV lanes, and road or parking pricing. Since these policies vary dramatically in terms of the scale of the impacts and their cost, different analytical approaches may be warranted in each case. Generally speaking, it is reasonable to assess the impacts of the employer-based policies by reducing the number of auto trips to specific destinations during peak hours by a percentage agreed to be reasonable to account for the relevant policies. This exercise can quickly become daunting in its detail, so it is best to acknowledge the effects and develop a quick and reasonable approach to account for the effects if necessary.

2.2.4.2 Evaluating Managed Lanes and Pricing Strategies

Managed lanes and in particular roadway pricing are crucial elements of some regions’ networks and nationally are becoming particularly relevant as States and regions consider how to pay for maintaining and expanding their road networks. However, models are typically not well equipped to evaluate such policies as HOV lanes, high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes, or tolled facilities. The consideration of managed lanes investments and in particular road pricing policies involves thoughtful consideration of how different travelers trade-off time and cost, along with a realistic representation of travel times and trip patterns.

While there are different methods that can be used to estimate demand for a managed lane or a toll facility (e.g., diversion curves, toll mode choice models, or traffic assignment methods that incorporate time and cost), for each approach to be successful it is recommended that the basic components leading to the demand estimate (trip distribution patterns by market segment, values-of-time, and travel time differences) be demonstrated to be reasonable and reliable. Traffic assignment models typically produce better estimates of volumes than speeds and, in the case of managed lanes, both are important.

Road pricing strategies also involve reliable estimation of the revenue potential for a facility, which adds an additional layer of complexity to the forecasting exercise. Typically, for projects involving private investment or bonding, a separate “investment-grade” forecasting study is carried out, which serves a different purpose from the NEPA study. While the NEPA travel forecasts are intended to form the basis for an informed Federal decision about the project, the “investment-grade” study provides assurances to investors that traffic levels will be sufficient to support the toll revenues anticipated for the project. The “investment-grade” study may involve different methodologies and produce different results from the NEPA study. If the results of the “investment-grade” study are released during the NEPA process, it is suggested that the study team explain differences between the two sets of forecasts in the NEPA documentation.[17]

2.2.4.3 Evaluating Transit Strategies

Transit provides important mobility benefits in congested corridors throughout the country and it is often necessary in a major NEPA study with highway alternatives to consider the potential benefits of upgrading transit services. While most models have the ability to represent transit to some degree, the models may not be a reliable predictor of travel by new transit modes, depending on the extent of the use of this aspect of the model. The introduction of a new transit mode in a corridor or a region is complicated to model and calls for careful consideration. The use of models that have been recently vetted and refined through the FTA’s New Starts project evaluation process[18] are most likely able to evaluate major transit alternatives. In situations where there is no transit modeling component, or one exists but has not been carefully reviewed, it is suggested that care be given to ensure that the transit model is working reasonably well, that transit model parameters are reasonable, and that transit markets and forecasts are validated.

2.2.4.4 Evaluating Integrated Land Use and Transportation Scenarios

From a travel demand forecasting perspective, the type of land use development can influence travel behavior and choices. A paper written by Cervero and Kockelman[19] provides the basic premise and foundation for subsequently developed sketch planning elasticity-based modeling methodologies. The “3D's” were eventually expanded to 4, and include land-use density, land-use design, destinations (i.e., the appeal of the places), and diversity in the attractions.

Incorporation of a 4D component into travel demand forecasting models is a very complex undertaking that, to be done correctly,requires extensive data collection to first observe how these components affect travel behavior, and then model the effects of urban design elements on each aspect of the travel model. Due to the high degree of complexity and high cost associated with such an endeavor, efforts to capture these effects have often utilized off-model adjustments based on elasticities, whereby auto tripsare removed to represent reductions in travel associated with specific land development characteristics. An additional and important layer of complexity is that models tend to capture some of these phenomena in some direct and indirect ways. Therefore, it is important for the study team to be very careful if they decide to apply additional off-model effects, and to document the need for the adjustments in addition to any effects captured by the model.

With research efforts continually developing new and improving existing technologies and methods, the state of the practice in land use and travel forecasting will never be static. Two particular methods that are becoming commonly used are integrated land use and transportation models and activity-based models, which are discussed below.

The use of integrated land use and transportation models is becoming more widespread, with implemented models in use in a number of metropolitan areas. Integrated models are designed to allow the two-directional interactions between land use development and transportation demand to be represented: for example, land use development increases demand for personal travel, while construction of new transportation infrastructure can affect land development patterns. The use of these models, while conceptually attractive, may add to the complexity of the analysis carried out by the study team.

Despite a long history of forecasting practice using traditional models, these tools have limitations, as described in TRB Special Report 288[20] and other publications. These limitations range from the theoretical (that aggregate four-step models do not reflect travel as a “derived” demand resulting from the needs of households and individuals to participate in activities) to the practical (that these models are fairly insensitive and lack detail needed to test some policies). In the past decade, more advanced “activity-based” forecasting approaches have been developed and implemented in a number of large- and medium-sized regions. These models offer expanded analysis capabilities, more behavioral, temporal, and spatial resolution, and better integration with long-term land use forecasting models and traffic micro-simulation models. However, there are many concerns with these models that are common with traditional four-step models: they are sequential systems, and they are subject to the same concerns regarding the quality of model input data and the robustness of the model calibration and validation. In addition, calibration and validation of an activity-based model system necessarily involves greater effort than one associated with a four-step model because of the more comprehensive treatment of all aspects of travel.

It is suggested that the study team consider the potential benefits but also the practical difficulties associated with these advanced techniques during their evaluation of the suitability of modeling methods and tools available to them. As with any tool used during analysis, if the study team chooses to use one of the advanced techniques discussed above, it is important to demonstrate its suitability. In many cases, the study team will not have an advanced model available to them or they will be faced with an analysis for which an advanced technique is not necessary.

There are substantive and procedural benefits from leveraging outside expert opinion. Lead agencies can use peer reviews to help ensure that the forecasting processes being applied meet the standards of professional practice and/or Federal, State, or local requirements. In addition, peer reviews of models inherently require an appropriate level of detailed technical documentation, and can have value for this reason alone. Finally, because forecasting can be a difficult and complicated process, an outside and objective perspective may be helpful.

There are several options for peer review of the forecasting work, including internal and external review approaches:

- Independent review of the travel forecasting methods and preliminary output by outside experts. A rigorous review would consist of a review of the model files and output, whereas a less rigorous review would cover the documentation only.

- Interagency panel of MPO, transit, transportation, and land use planning agencies. This review would be conducted by the stakeholder agencies in the study area to ensure the use of the best available forecasts and data. Effectively, this panel would form a technical advisory group for the project.

- Review of the forecasting effort by the agency responsible for maintaining the model. This can help ensure that the model was applied correctly, facilitate consistency across studies, and leverage the appropriate government resources and expertise.

- Internal, semi-independent review by senior staff from the study team. Such an effort would be analogous to the formal review required of engineers who produce designs.

The need for and appropriate level of review depends on the circumstances of each study. It is critical to engage in a peer review at a stage in the study where the findings of the review can still be taken into account when conducting the analysis. More complicated analyses, or situations where new methods have to be implemented, will obviously require more time.[21]

This section of the guidance discusses the importance of ensuring the suitability of modeling methods, tools, and underlying data. It is important for the study team to produce documentation that describes their review of the tools that they choose to use to support their analysis, and to document any updates or improvements that they identified as necessary for the analysis.

It is also important for the study team to focus this documentation on the needs and scale of the analysis that they are undertaking. The MPO or DOT that maintains the regional travel demand model is likely to publish a calibration report that can be referenced to demonstrate that the model is calibrated at a regional level; however, this report is unlikely to deal specifically with calibration for the study area for a particular project. Therefore, it falls to the study team to demonstrate that the travel demand model is adequately calibrated in their study area.

Other elements to consider for inclusion in the documentation are:

- Demonstration that the tools have the capability to forecast the range of policies that will be developed in the alternatives analysis

- Discussion of the appropriateness of using new or advanced methods that might be considered a departure from typical practice, given the context of the application

- Results of any peer reviews or an explanation detailing why no peer review was required.

As with forecasting needs, the key purpose of this documentation is to demonstrate that these issues have been considered by the study team. Again, the documentation can demonstrate the process used to make decisions relating to model suitability and record who was involved in the decision-making process.

The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) regulations for implementing the provisions of NEPA require that the lead agencies insure the professional integrity, including scientific integrity, of the discussions and analyses in environmental impact statements,[22] and this and other elements of documentation discussed in this guidance can help the lead agencies to demonstrate that they are meeting this requirement.

Back to Top

Scoping is a collaborative process involving the lead agencies, resource and regulatory agencies, and the public. Typically, this is how a NEPA study begins, and is intended to initiate activities in the most efficient and effective direction. Early consideration is given to determining what factors and resources will be issues of concern during the NEPA process and therefore have an impact on the decision being made, and conversely, what factors and resources are not likely to impact decision making.

SAFETEA-LU Section 6002 provided additional direction regarding the scoping process for environmental impact statements (EISs) by specifying that lead agencies collaborate with participating agencies on the methodologies to be applied and the level of detail required in the NEPA study.[23] Participating agencies are those Federal and non-Federal agencies that have an interest in the project. These agencies may also be cooperating agencies, meaning that they have special expertise or legal authority such as a permit approval. Such collaboration can be advantageous when conducting categorical exclusions or environmental assessments as well, although it is not required. The goal of the scoping process is to provide an opportunity for agencies and the public to raise critical issues and concerns early in the NEPA study so that these can be adequately considered as the NEPA study moves forward.

For this reason it is important to reach early agreements on the methodologies and conduct of the many technical studies that will support the overall NEPA analysis. The focus of this guidance is travel and land use forecasting, but the forecasts are relied upon as inputs for other technical studies, such as air quality, noise, and land development effects. Therefore, to ensure that the effects of potential alternatives are reasonably estimated, it is important for the travel forecast to provide an adequate representation of the travel patterns and volumes to be expected with each of the alternatives. Because future land use forms the basis for demand in the travel forecasting process, it is suggested that agreements be reached first on future land use scenarios for the alternatives and the methodologies to be used to develop those estimates.

The primary reason for reaching agreement early during the scoping process is to minimize the cost and schedule risk associated with “backing up” or re-doing work during the study. It is not uncommon during the NEPA process, particularly during alternatives analysis and evaluation, for the public and agencies to question the work done prior to that stage. Because not everyone will be 100% satisfied with the alternatives under consideration, it is natural for this questioning to take place. Having documentation on the agreements reached and the assumptions used for the land use and travel forecasts will facilitate the process to move forward with minimal delay and disruption. It is important to explain why the agreements were reached and how the team arrived at the assumptions used for land use and travel forecasting. In the absence of these agreements, the likelihood that the process may cycle back to this stage increases and could result in additional delay to the study and increased costs. Several agencies have developed procedures, such as templates, to assist with reaching consensus during scoping and documenting the agreed upon analysis approach.[24]

It is important for NEPA study teams to recognize that effective use of the scoping process is integral to a successful forecasting effort, since the scoping process sets the tone for participation throughout the study and can identify key issues germane to the forecasting exercise. The definition of a successful forecasting effort would be one where there is broad acceptance of the outputs from that effort. As described above, getting to that consensus requires early agreement on the inputs to the forecasting process and methods used. In addition to land use, it is important that the agreements cover all aspects of the forecast effort, such as whether the model accounts for modal splits, tolling, “induced” travel, and other items that relate to the range of alternatives being considered. All of these considerations are discussed elsewhere in this guidance.

Agencies would be well served to adopt written procedures for scoping all studies, regardless of the type of NEPA analysis. Simply stated, scoping sets the framework for everything that follows. It is suggested that the level of effort devoted to the scoping process be tailored to the context of the proposed project and/or the range of alternatives. Typically, the level of scoping effort associated with the replacement of a deficient bridge on an existing site would be different from the level of effort for a potential freeway in a new location, or a new commuter rail line. In addition, the roles of forecasts are different under each of those scenarios and would also require a commensurate level of effort in terms of reaching early agreements on how they will be determined.

As discussed above, it is critical for the study team to document their work on scoping of the analysis and their interaction with other agencies, recording the broad agreements reached and the assumptions used for the land use and travel forecasts. This documentation can then be used throughout the study as a reference during analysis and later to demonstrate what decisions were made and the process by which decisions were made, and to identify who was involved in making those decisions.

Back to Top

The CEQ regulations require lead agencies to “rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives.”[25] This provision establishes a standard for NEPA studies to treat each alternative in an unbiased manner so that the related benefits and impacts can be estimated and compared across alternatives. For EISs, the regulations go on to say that the study “shall provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and shall inform decision-makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives which would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment.”[26] In addition, the regulations say that the alternatives analysis is “the heart of an environmental impact statement.”[27] From a land use and travel forecasting perspective, these provisions have direct relevance in how forecasting methods are applied for the purposes of analyzing alternatives.

The CEQ regulations define the effects and impacts that Federal agencies are to address and consider in satisfying the requirements of the NEPA process. These effects include direct effects, indirect effects, and cumulative impacts:

- Direct effects are caused by the action and occur at the same time and place (40 CFR § 1508.8).

- Indirect effects are caused by the action and are later in time or farther removed in distance, but are still reasonably foreseeable. Indirect effects may include growth-inducing effects and other effects related to induced changes in the pattern of land use, population density, or growth rate, and related effects on air and water and other natural systems, including ecosystems (40 CFR § 1508.8).

- Cumulative impact is the impact on the environment, which results from the incremental impact of the action when added to other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions, regardless of what agency (Federal or non-Federal) or person undertakes such other actions. Cumulative impacts can result from individually minor but collectively significant actions taking place over a period of time (40 CFR § 1508.7).

The terms "effect" and "impact" are used synonymously in the CEQ regulations (40 CFR § 1508.8). "Secondary impact" does not appear, nor is it defined in the CEQ regulations or related CEQ guidance, but the FHWA has used the terms “secondary impact” and “indirect effect” interchangeably.[28]

There are several available resources that discuss the distinctions between these types of effects and provide guidance on considering and measuring them.28, [29] From a travel forecasting standpoint, there are numerous transportation-related impacts that are measurable and may be meaningful in an alternatives analysis. Following are examples of impacts that illustrate the type of information that comes from a travel forecast, or is closely related to travel forecasting output, organized into direct effects, indirect effects, and cumulative impacts.

2.4.1.1 Direct Effects

Transportation-related direct effects are generally well understood. Table 2 presents a brief list of typical direct effects that have their basis in travel and/or land use forecasting, including how each one is usually sourced:

Table 2: Typical Direct Effects Estimated using Outputs from Forecasts

| Effect |

Effect Type |

Effect Source |

| Congestion /Delay |

Peak hour/period level of service

|

Direct output of traffic assignment and/or post processed output to produce intersection turning movement volumes (see section 2.4.5)

|

|

Hours of congestion

|

|

Intersection level of service

|

|

Point-to-point travel times

|

| Travel Choices |

Mode shares

|

Direct output of mode choice model

|

|

Transit boardings and loadings

|

Direct output of transit assignment

|

| Revenue |

Toll revenue, transit revenue

|

Revenue forecasts based on traffic and transit assignment results

|

| Environmental/Social |

Noise

|

See section 2.6.1

|

|

Air quality

|

See section 2.6.2

|

|

Traffic diversion

|

Direct output of traffic assignment

|

|

Travel benefits for different socioeconomic groups

|

Post processed travel model outputs by socioeconomic groups

|

|

Accident rates

|

Post processed traffic assignment by functional class, and changes in non-motorized trips and shares from trip generation and mode choice models

|

2.4.1.2 Indirect Effects

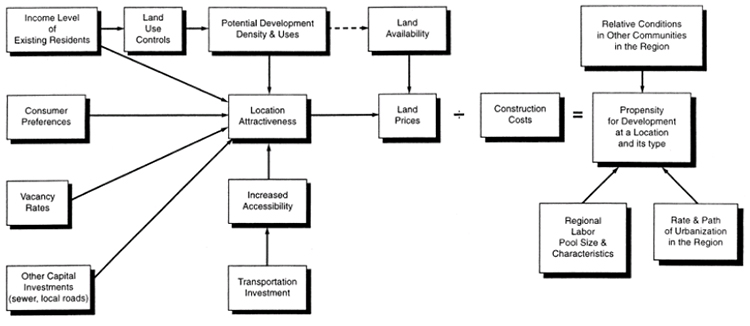

Potential changes in land development patterns due to a transportation investment are typically examined as part of an indirect effects assessment, particularly on major projects.[30] These effects are not easy to forecast. The study team may undertake a land development impact assessment through the use of integrated land use and transportation models, the application of gravity or other more simplified models, or simply an analysis of regional and local trends. In some studies the team may also choose more qualitative methods such as surveys, interviews with developers, discussions with local planners, or the Delphi or expert panel process. These are considered further later in this document.

The FHWA’s Interim Guidance on Indirect and Cumulative Impacts explains that a proposal for a new alignment project in an area where no transportation facility currently exists, or one that adds new access to an existing facility may indicate an increased potential for project-related indirect impacts from other distinct but connected actions, such as the opening of access to land with a new highway leading to new development.[31] Likewise, the purpose and need of a proposed project that includes a development or economic element might establish an indirect relationship to potential land use change or other action with subsequent environmental impacts.[32] It is important for the lead agencies to identify potential indirect impacts of the transportation proposal early in the NEPA project development process.

Land development effects and potential redistribution of growth within a region may be analyzed more robustly at the regional level and during the regional planning process. Increasingly, MPOs, DOTs, and other agencies are using integrated land use and transportation forecasting procedures in the planning process to better understand the interrelationship between growth and the transportation system. It is therefore possible that the study team can glean insights at the project level from a regional planning analysis. One advantage of a regional analysis is that the study team can consider the region-wide growth pressure dynamics.[33]

Table 3 presents a brief list of typical indirect effects that may be considered in a NEPA study that are based on or use forecasting outputs:

Table 3: Typical Indirect Effects That are Based on or use Forecasts

| Effect |

Effect Type |

Effect Source |

| Land Use |

Residential development

|

Based on land development impact assessment

|

|

Commercial development

|

| Revenue/Economic Growth |

Increased tax revenue

|

Based on fiscal impact assessment of land development forecasts

|

|

Regional economic growth

|

| Environmental/Social |

Noise

|

See section 2.6.1

|

|

Air quality

|

See section 2.6.2

|

|

Visual impact of development

|

Based on land development impact assessment

|

|

Floodplain and wetland encroachment

|

|

Fragmentation of habitat

|

2.4.1.3 Cumulative Impacts

The FHWA’s Interim Guidance on Indirect and Cumulative Impacts states that cumulative impact analysis is resource-specific and generally performed for the environmental resources directly impacted by a Federal action under study, such as a transportation project. However, not all of the resources directly impacted by a project will require a cumulative impact analysis. The resources subject to a cumulative impact assessment should be determined on a case-by-case basis early in the NEPA process, generally as part of early coordination or scoping.[34]

Two types of direct impacts, both measured and part of travel model output, have potentially important cumulative effects: air emissions and noise. The study team will typically evaluate the cumulative effects on air quality during the regional air quality conformity modeling process. The study team can measure the cumulative noise impacts through a noise model and an understanding of existing noise levels.