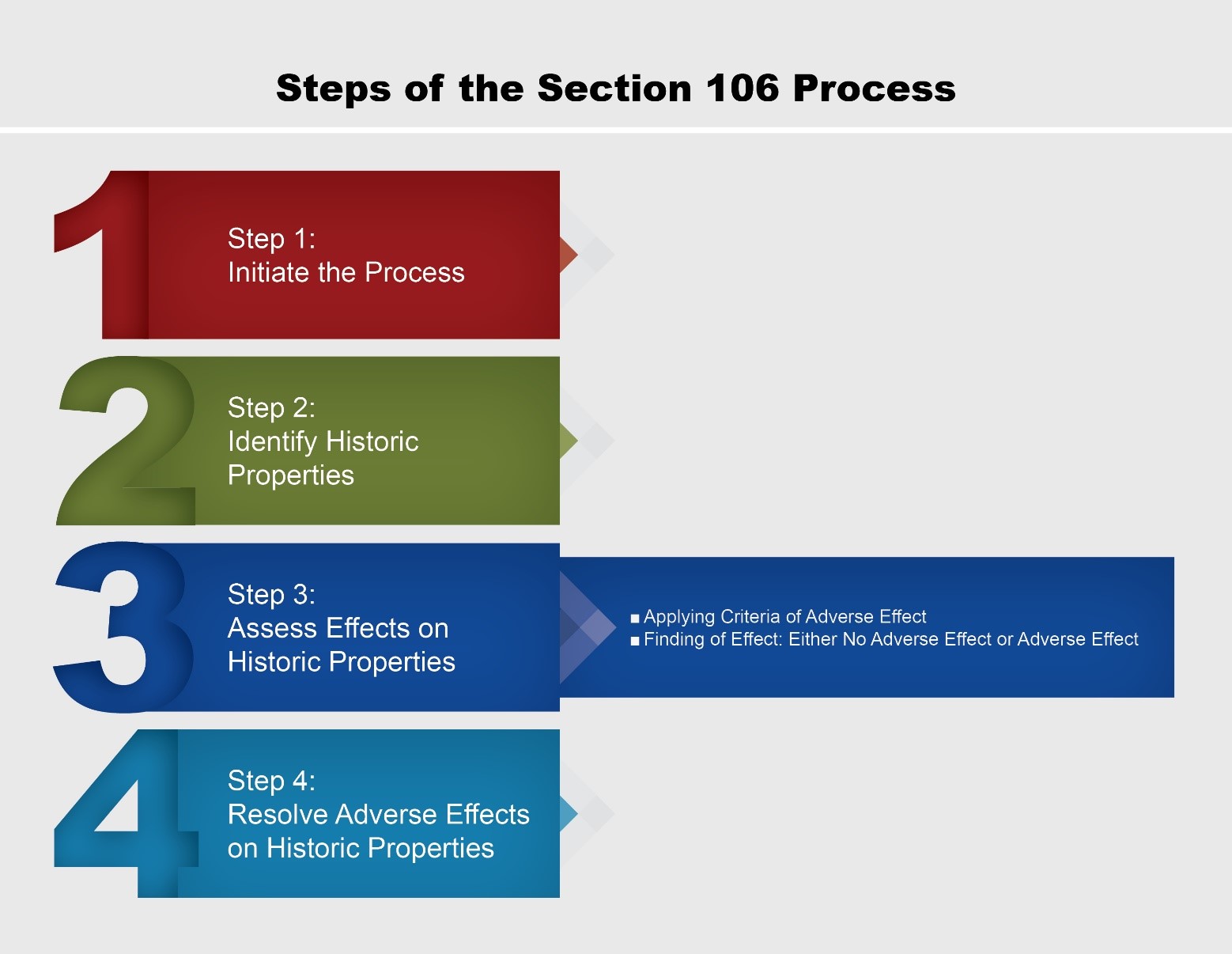

Steps of the Section 106 Process

Step 3: ASSESSING IF A PROJECT WILL HAVE AN ADVERSE EFFECT ON HISTORIC PROPERTIES

Step 3 of the Section 106 process is assessing effects on historic properties. See full description here

A project will have an adverse effect on a historic property if the project may alter any features that contribute to its eligibility for the National Register in a way that would diminish the integrity of the property. Specifically, the Criteria of Adverse Effect section of the regulations states:

An adverse effect is found when an undertaking may alter, directly or indirectly, any of the characteristics of a historic property that qualify the property for inclusion in the National Register in a manner that would diminish the integrity of the property’s location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, or association. Consideration shall be given to all qualifying characteristics of a historic property, including those that may have been identified subsequent to the original evaluation of the property’s eligibility for the National Register. Adverse effects may include reasonably foreseeable effects caused by the undertaking that may occur later in time, be farther removed in distance or be cumulative. (See 36 CFR Part 800.5(a)(1)).

As noted above, determining if a project will have an adverse effect on historic properties is based on the aspects of integrity which are present in the property and should be defined during the National Register evaluation process, see How is a property determined eligible for the National Register?

The stone workmanship on the Roosevelt Bridge in Austin, Minnesota, is one of the characteristics that qualifies the bridge for listing in the National Register. The rehabilitation project shown here was done in a way that retained the bridge’s integrity of materials and avoided an adverse effect. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt.

A property need not retain all seven aspects of integrity to be deemed eligible; however, if the assessment of a property’s integrity is not adequate, it will be difficult to determine if an FHWA action will result in an adverse effect.

Examples of adverse effects include:

- Physical destruction, damage, or removal of all or part of the property

- Alterations to a property’s qualifying characteristics

- Changes to a property’s setting when the setting contributes to its historic significance (e.g., changes to the environment around the property)

- Introduction of elements such as noise or visual impacts that diminish a property’s setting when setting is a contributing feature

A circa 1840 Italianate house in Lincoln County, Missouri, was displaced by an interchange. The state completed archaeological investigations, documentation of the house, and salvage of architectural elements to mitigate the adverse effect. The new interchange reduced crashes in the community by 90 percent; there had been approximately five fatal crashes annually but none since construction of the interchange. Photograph courtesy of the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Interstate Highway 95 in Northeast Philadelphia encroached upon the setting of the Henry Longfellow School, built in 1915. Pennsylvania Department of Transportation has a long-term, multi-phase project to rebuild the Interstate. Changes to a property’s setting when the setting contributes to its historic significance and introduction of visual impacts that diminish a property’s setting are adverse effects. The school was determined eligible under Criterion C: Architecture as an example of the Utilitarian Classical variety in public school architecture. Photograph courtesy of A.D. Marble & Company.

The baseline for assessing effects is the property’s existing condition, recognizing that its condition may have already undergone some changes from its original form. Some bridge types, such as trusses and girders, may be relocated as a means of avoiding or minimizing adverse effects if important design features are retained and the new setting is appropriate. For more information, see Section 106 regulations at 36 CFR Part 800.5(a)(2) for all seven examples of adverse effects. Also see Indirect Effects in Additional Information for guidance from the ACHP.

Applying the Criteria of Adverse Effect

FHWA is responsible for applying the criteria of adverse effect on a property-by-property basis in consultation with SHPO/THPO to determine whether a project may have an adverse effect on any historic properties within the APE. If a project will have an effect on historic properties, but the effect does not meet the criteria of adverse effect on any of the historic properties identified within the APE for the project, FHWA makes a finding of No Adverse Effect. FHWA is responsible for making the determination, documenting the finding, and notifying SHPO/THPO and consulting parties of its finding along with the requisite documentation. See Guidance for Documentation for Consultation in Additional Information for more information on the requisite content. FHWA should also seek concurrence with its finding from any Tribe or NHO that has made known to FHWA that they attach religious and cultural significance to a historic property subject to the finding.

The Gateway Refrigeration Building in St. Louis City, Missouri, before (left) and after (right) construction of the new Veteran’s Memorial/Stan Musial Bridge. In the days before every house had a refrigerator/freezer, large-scale cooling was done in industrial buildings like this one. Because the bridge built was smaller than the one originally planned, the Gateway Refrigeration Building was avoided during design and it was determined the project would have a finding of No Adverse Effect on the building. Photograph courtesy of the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Finding of No Adverse Effect or Adverse Effect

In the case where there may be an adverse effect to one or more of the historic properties within the APE for the project, FHWA or any of the consulting parties can propose measures to avoid the adverse effects. Avoidance measures may mean selecting a different alternative or making project modifications to limit impacts to historic properties. It is important to note that a finding of Adverse Effect may alter the selection of the preferred alternative under NEPA when the magnitude or number of impacts on historic properties is great, and/or when resolving the adverse effect would be extremely difficult. FHWA and its applicant should make a good faith effort to consider whether such measures are reasonable solutions to avoiding adverse effects.

A newly constructed beamguard on a bridge within the boundary of the Taliesin National Historic Landmark in Wisconsin was painted with a natural finish, instead of the typical metallic finish, to better fit the aesthetic of the historic property and avoid an adverse effect. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt.

If such measures become part of the project, the outcome would be a finding of No Adverse Effect and the fourth step of the process can be avoided (i.e., resolving adverse effects). Two project examples are provided to illustrate how a finding of No Adverse Effect can be accomplished, including a complex example that shows how design modifications incorporated into a project can result in a finding of No Adverse Effect. Should the identified avoidance measures not be incorporated into the final project, or if the project is modified such that impacts to historic properties are changed after the Section 106 process has been completed, FHWA is responsible for reopening the Section 106 process to take into account the impacts of the modified undertaking on historic properties.

The parties have 30 days after receiving the No Adverse Effect notification with adequate supporting documentation to raise an objection. Even when the SHPO/THPO concurs with the finding before the end of the 30-day review period, FHWA is obligated to wait the full 30 days to allow all consulting parties the full amount of time for review. If no objections are raised during the review period, the Section 106 process is complete. FHWA may finalize the finding, document the finding to the project file, and proceed with the project.

A project adjacent to the Taliesin National Historic Landmark in Spring Green, Wisconsin, resulted in a finding of No Adverse Effect after consultation and modifications to project plans, such as the beam guard paint shown earlier. Photograph courtesy of Mead &Hunt.

If there is an objection in writing to a finding of No Adverse Effect within the 30-day review period, FHWA should consult with the objecting party to resolve the objection or request the ACHP to review the finding (see 36 CFR Part 800.5(2)). The ACHP will also review the finding if FHWA consults with the objecting party but cannot resolve the objection. Objections from parties other than SHPO/THPO may not require a formal review of the finding, but should be addressed before any objection escalates to involve SHPO/THPO or the ACHP. This is not a situation to be taken lightly as the involvement of the ACHP may require additional time, documentation, and steps, including comments from the ACHP to the head of FHWA.

If there could be an adverse effect to one or more of the historic properties identified, FHWA makes a finding of Adverse Effect, informs the ACHP and other parties about the adverse effect, and moves on to the next step in the process. See Additional Information for e106, an easy electronic way to notify the ACHP. If the project may have an adverse effect to a National Historic Landmark (NHL), 36 CFR Part 800.10 requires FHWA not just to notify, but to invite the ACHP to participate in consultation. In addition, FHWA must also notify the Secretary of the Interior of any consultation where there may be an adverse effect to an NHL. This notification is made through the NHL program at the pertinent National Park Service regional office.

As with other parts of the Section 106 process, the responsibility for the finding of No Adverse Effect and related actions may be delegated to a State DOT either through the NEPA Assignment program or through a fully executed delegation PA. In the case of a Section 106 delegation PA, FHWA is still ultimately responsible for the findings and decisions. FHWA should also ensure that the personnel providing specific information regarding historic properties and project effects on these properties are qualified professionals meeting the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications Standards. It is also important to note that effect findings can differ between states.

Project examples are provided to illustrate in more detail the various outcomes of the Section 106 process.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.