Steps of the Section 106 Process

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Indirect Effects

For guidance on indirect effects to historic properties that may be caused by an undertaking, see the 2019 ACHP memorandum Court Rules on Definitions; Informs Agencies on Determining Effects.

Electronic Section 106 Documentation Submittal System (e106)

The ACHP offers a voluntary Electronic Section 106 Documentation Submittal System (e106) for use by any Federal agency (or officially delegated non-Federal entity) when:

- Notifying the ACHP of a finding of Adverse Effect,

- Inviting the ACHP to be a consulting party to resolve adverse effects, or

- Proposing to develop a PA for complex or multiple undertakings.

FHWA is strongly encouraged to submit Section 106 documentation for these purposes using e106, as it expedites a critical step in Section 106 review.

Emergency Situations

The Section 106 regulations include special provisions for declared emergency situations at 36 CFR Part 800.12. The best preparation for such situations is through a programmatic agreement that sets up specific provisions for dealing with historic properties in the case of emergencies, and many statewide FHWA PAs include such provisions. In the absence of statewide procedures, the regulations establish an expedited process in the case of emergencies officially declared by the Federal, State, or tribal government, when a Federal undertaking will be implemented within 30 days after the emergency is formally declared. As stated in the regulations, immediate rescue and salvage operations to preserve life and property are exempt from the requirements of Section 106.

An emergency such as this washout of State Highway 78 over the Red River in Oklahoma is covered under special provisions of the Section 106 regulations. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt.

Post-Review Discovery

The regulations also provide for situations where a previously unknown historic property or unanticipated effects to a known property are discovered after the Section 106 process has been concluded. See Section 106 regulations at 36 CFR Part 800.13 for complete text. As with emergency situations, the best approach is to have a statewide protocol with standard procedures in place, as is included in many statewide PAs. Absent a customized procedure and provided the efforts to initially identify historic properties were adequate, the provisions under the regulations allow for the agency official to make “reasonable efforts to avoid, minimize or mitigate adverse effects.” Depending on whether construction on the project has commenced, the regulations include an expedited process for notifying SHPO/THPO and Tribes, receiving their responses, and considering their input in reaching a decision about treatment of the historic property. Construction work in the immediate area of the discovery may be suspended to allow time to evaluate the property, consult to resolve the impacts, and put agreed-upon measures in place. It is usually agreed to allow other work on the project to proceed during this time as long as that work would not affect the historic property discovered. If the discovery occurs on tribal lands, FHWA must abide by all tribal regulations and obtain the concurrence of the Tribe on the proposed actions.

Guidance for Documentation for Consultation

FHWA provides the documentation for consultation specified at 36 CFR Part 800.11(e) to all consulting parties. The requisite content is specific to the determination made by FHWA as specified below.

Finding of No Historic Properties Affected

Documentation shall include:

- A description of the undertaking, specifying the Federal involvement, and its APE, including photographs, maps, drawings, as necessary;

- A description of the steps taken to identify historic properties, including, as appropriate, efforts to seek information pursuant to 36 CFR Part 800.4(b); and

- The basis for determining that no historic properties are present or affected.

Finding of No Adverse Effect or Adverse Effect

Documentation shall include:

- A description of the undertaking, specifying the Federal involvement and its APE, including photographs, maps, and drawings, as necessary;

- A description of the steps taken to identify historic properties;

- A description of the affected historic properties, including information on the characteristics that qualify them for the National Register;

- A description of the undertaking's effects on historic properties;

- An explanation of why the criteria of adverse effect were found applicable or inapplicable, including any conditions or future actions to avoid, minimize or mitigate adverse effects; and

- Copies or summaries of any views provided by consulting parties and the public.

See also Section 106 regulations, 36 CFR Part 800.11.

Project examples are provided to illustrate the various outcomes of the Section 106 process.

For an example showing one State DOT’s approach to content and formatting of the finding of No Adverse Effect, see the Caltrans’ Finding of No Adverse Effect Format and Content Guide, which can be found on the agency’s webpage.

Examples of Project Types and Activities and Conditions Frequently Listed in State PAs with Minimal Potential to Affect Historic Properties

The following are some examples, from state delegation PAs of the types of projects and activities that would have minimal potential to affect historic properties:

- Curb, gutter, and sidewalk improvements

- Guardrail installation

- Repaving, and pavement rehabilitation, resurfacing and reconstruction

- Lighting and signalization installation or replacement

- Repaving existing shoulders

- Intersection improvements

These project types must also meet certain conditions, which are also specified in the state PAs. For example, a project must be limited to:

- Existing right-of-way

- Areas that have been previously disturbed

- Areas that have been previously inventoried to current historic property inventory standards with negative results

- An area not located within or adjacent to a historic property

- In-kind replacement of roadway features (such as signage and signalization)

See FHWA’s list of Statewide Section 106 Programmatic Agreements that includes project screening.

Section 106 Delegation Programmatic Agreements

A National Cooperative Highway Research Program study titled Section 106 Delegation Programmatic Agreements: Review & Best Practices demonstrated the value of screening projects to streamline reviews and reduce the cost and timing of project delivery. This study showed that through the use of a screening process, the majority of FHWA-funded and approved projects will not require further Section 106 review. Screening allows FHWA, State DOTs, SHPOs and other consulting parties to focus their review efforts on projects that have the potential to adversely affect historic properties.

Mitigating Adverse Effects

When it is not possible to avoid or minimize an adverse effect on a historic property, FHWA will consider measures to mitigate the adverse effect. For archaeological sites, mitigation usually involves excavating those portions of the site that will be lost as a result of a project, and retrieving the important information and data contained within the site. This type of excavation is normally referred to as “archaeological data recovery.” Mitigation for adverse effects to historic properties that are part of the built environment is typically documentation. Documentation follows Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), Historic American Engineering Record (HAER), or Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) standards as appropriate, or may follow a state-specific standard.

Many FHWA DOs and state DOTs, in partnership with SHPOs and Tribes and other consulting parties, will identify and agree to conduct what is referred to as “alternative mitigation” or “creative mitigation.” This may be in addition to the above basic approaches to mitigation, and in some cases will be in lieu of these standard approaches. FHWA’s policy regarding mitigation that utilizes public funding, including alternative mitigation, is that it, “...represents a reasonable public expenditure after considering the impacts of the action and the benefits of the proposed mitigation measures” (23 CFR Part 771.105(e)).

Types of alternative mitigation include but are not limited to following:

- Publications

- Training/workshops

- Websites, social media, and crowdsourcing apps

- Reuse and/or repurpose salvaged materials (e.g., historic bridge or bridge components)

- Educational materials, programs, or exhibits

- Community engagement programs

- Films/videos

- Design details incorporated into projects

This 1928 pony truss bridge was relocated from a public roadway in Wisconsin to a private garden that is open to the public. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation financially assisted with the move to mitigate for the adverse effect of removing this historic property to a compatible new setting. Photograph courtesy of John Lamm.

Benefits to using alternative mitigation include the following:

- Promoting appreciation and protection of historic properties

- Meeting the preservation needs of communities and interested parties

- Increasing inclusivity and open dialogue with underrepresented communities affected by a project

- Benefiting communities economically (e.g., incorporation into tourism plans)

- Promoting and protecting Tribal culture and traditions

- Reaching a maximum audience through social media and technology to promote the value of historic properties and historic preservation in general

- Demonstrating FHWA and State DOT commitment to environmental stewardship and the community benefit of their projects

Additional information on alternative mitigation can be found on the ACHP’s website. Provided below are successful examples of alternative mitigation from around the country for a variety of historic properties.

Publications

Illustrated publications can provide meaningful mitigation because they have an educational component that highlights the significance of the affected property(ies) and promote appreciation of similar properties and related historic trends within a community, region, or state. Provided below are some examples:

- Transportation in and about Farmington, prepared to mitigate replacement of a historic 1924 bridge carrying S. Main Street/State Route 153 over the Cocheco River. The document provided educational outreach on transportation trends in Farmington, New Hampshire.

- Bridging the Mighty Red, Red River Crossings Between Oklahoma and Texas, prepared to mitigate the replacement of the State Highway 79 Bridge over the Red River.

Technical Trainings/Workshops

Alternative mitigation that includes trainings or workshops promotes appreciation and knowledge about the resources that can have a lasting impact. The PA for Louisiana’s historic bridges included mitigation measures to address anticipated future adverse effects to historic bridges. Among these measures was development of a training workshop by the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Louisiana Transportation Research Center to provide guidance and best practices related to preventative maintenance, preservation, and rehabilitation of historic bridges. Training workshops were scheduled every two years starting in 2015 and will continue until PA signatories determine it is no longer warranted. This type of mitigation promotes appreciation and technical knowledge about appropriate treatment options for historic bridges among engineers, bridge owners, and others involved in rehabilitation projects.

Community Engagement and Events

Mitigation for construction of the Border West Expressway in El Paso, Texas, addressed adverse effects to the buildings and community of Chihuahuita, one of the oldest Hispanic neighborhoods in the city and location of an original border crossing with Mexico. An existing elevated highway above portions of the community would be expanded as part of the project, and would extend further into the neighborhood. Initial efforts at mitigation involved educational posters focused on adobe construction techniques (many of the buildings in the community were adobe), community work and play, and immigration and segregation. However, these mitigation measures were created from an Anglo perspective and were not well-received by the community. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) conducted additional engagement with the community and local educators to identify mitigation measures to directly benefit the community. A new poster showcasing Chihuahuita artists’ murals on the piers of the existing elevated highway and an accompanying history booklet on the community, in English and Spanish, were developed, along with a supplemental booklet with activities and resources tied to state education standards. A community celebration to unveil the poster and booklets was also held. The educational booklet can be found on TxDOT’s webpage.

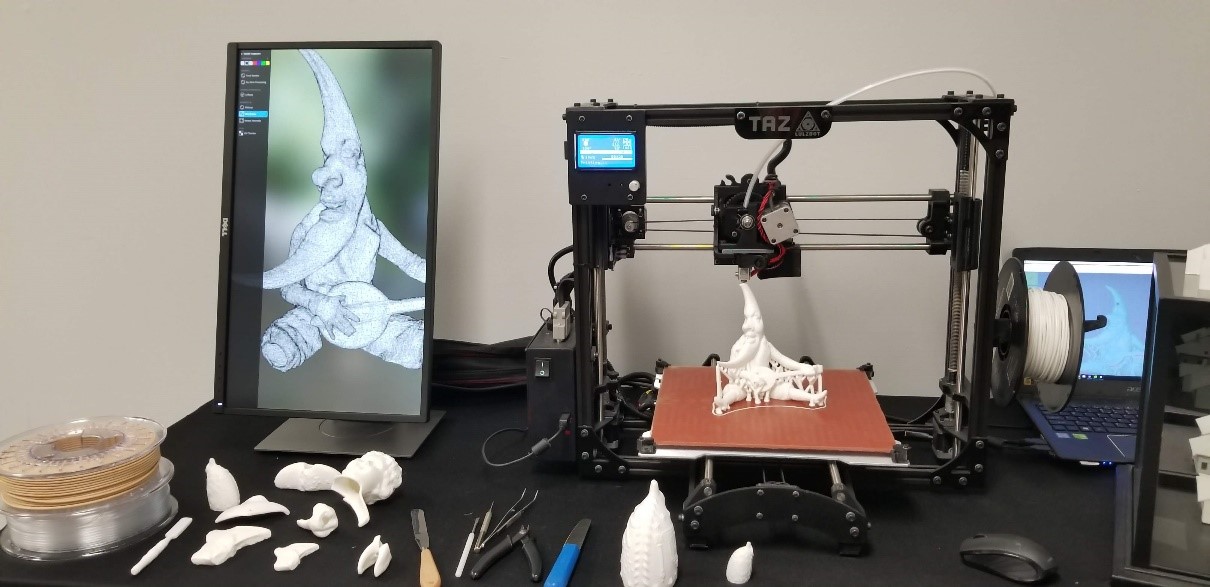

The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation undertook a long-term, multi-phase project to rebuild and improve Interstate Highway 95 (I-95) within Philadelphia. Archaeological excavation within the project area, referred to as the I-95 Girard Avenue Interchange Improvement Project, identified, 11 Native American sites and 20 historical sites and recovered over 1.5 million archaeological artifacts, to date. Alternative mitigation has been key in meeting public expectations regarding ongoing sensitivity to cultural materials recovered during excavations, and disseminating information in a manner that keeps the public engaged in this ongoing project. The project has its own professional journal, live interactive reporting, and a public archaeology center. The public archaeology center includes exhibits, laboratory stations, and augmented reality displays that help decipher and interpret the activities of Native Americans, immigrants, and descendants, creating an inclusive story of life along the Delaware River. Visitors can also interact with project archaeologists at the center about the on-going work. Additional information about the archaeology center and project can be found at these links: http://diggingi95.com/ and http://95revive.com/.

The public archaeology center features augmented reality displays made possible through a combination of 3D scanning technology, ScanStudio, Autodesk ReCap, and Geomagic software that recreates recovered artifacts and enables visitors to view items on their smart phones through an augmented reality app. Photograph courtesy of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation.

Reuse and Repurpose Salvaged Materials

After construction of a new bridge led to demolition of the eastern span of the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge, steel from the historic bridge was made available for reuse in public projects throughout California. Numerous artists, architects, landscape architects, planners, and other design professionals submitted proposals and 15 projects were competitively selected by a committee under the direction of the Oakland Museum of California and in coordination with the California Department of Transportation, Bay Area Toll Authority, and California Transportation Commission. Selection criteria included projects that celebrated the historic bridge, its history, or its significance and iconic status. Salvaged bridge components and materials were provided free of charge to the chosen recipients. More information can be found here.

Collaboration with Tribes

Cultural resource studies and consultation for a planned expansion of U.S. Highway 20 through Iowa’s Ida, Woodbury, and Sac Counties identified a significant Native American landscape. Through consultation with affected Tribes, and working with Iowa Department of Transportation engineers and design team, many historic properties associated with the Tribes were avoided, but the project resulted in an adverse effect. As mitigation, the Iowa DOT collaborated with Tribes to produce a film entitled Landscapes that Shape Us: Cultural Resources Mitigation for Highway U.S. 20 Project. The film received FHWA’s 2019 Environmental Excellence Award.

Alternative Documentation Methods

Although HAER, HABS, and HALS documentation is used as a standard approach to mitigation, there are opportunities to make these records of historic properties widely available to the public. One example is an online library of bridge HAER documents that the Oklahoma Department of Transportation prepared and maintains for historic bridges within the state replaced since 2000. Each document includes a short description, current status (demolished or bypassed), and link to the location for bridges that have been bypassed and left in place.

Programmatic Mitigation

A PA for the Milwaukee County Parkway System in Texas, which is eligible for the National Register, specified mitigation measures for the past and future loss of historic bridges in this county-wide network of historic parkways and related resources. Mitigation measures included:

- Design guidance for new bridges to maintain the rustic aesthetic of the original bridge while accommodating current standards.

- Reconnaissance-level inventory of resources within the entire parkway system.

- Preparation of National Register Multiple Property Documentation for the parkway system.

- Future completion of individual National Register Nominations for parkways adversely affected by Federal undertakings.

- Preparation of an illustrated booklet about the history, development, and significance of the parkway system.

This approach to mitigation is unique in that it addressed programmatically for past losses and pooled public money to help efficiently address future adverse effects to individual resources within the parkway system. City and county project applicants contributed funds toward the pool each time a project was proposed that would affect a historic bridge and/or parkway. With more than 60 historic bridges, this proved an effective means to address the County’s future Section 106 responsibilities. The Historic Properties Management Plan for county parks is a blueprint for preserving elements of the parkway system.

Aesthetic Treatments and Restoration

Replacement of the 1953 State Highway 82/Grand Avenue Bridge over the Colorado River, I-70, and the Union Pacific Railroad near downtown Glenwood Springs, Colorado, would result in an adverse effect to the historic bridge and indirect adverse visual effects to six adjacent historic properties. The visual impacts would result from the construction of a new wider and taller bridge. The project featured a package of mitigation measures, some standard and others creative:

- HAER Level II documentation of the historic bridge

- Aesthetic treatments in the design of the new bridge, roadway, and sidewalk elements that do not detract from the materials or architectural styles of nearby historic properties

- Restoration of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad – Aspen Branch connection to preconstruction conditions

- Temporary noise mitigation during nighttime detours during the demolition and construction of the new bridge, to reduce noise impacts on nearby historic properties, especially those operated as businesses

Additional information about the project and mitigation measures can be found here.

MOAs and PAs – Guidance, Samples, and Tracking Commitments

The ACHP offers several web resources that support the preparation and review of MOAs and PAs:

- The guidance on Section 106 agreement documents assists Federal agencies and others in developing, implementing, and concluding such agreements.

- The Section 106 Agreement content checklist helps ensure that the MOA or project PA includes the administrative stipulations and other clauses and information that should be found in every Section 106 agreement document.

- The Section 106 Agreement reviewer’s guide serves as a tool for reviewers of MOAs and project PAs.

For an example of how states can track commitments made in the MOA or PA, see Washington State DOT’s procedures to track environmental commitments and FHWA’s Interagency NEPA & Permitting Collaboration Tool, which has an environmental commitment tracker.

Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act, and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.