Eco-Logical: An Ecosystem Approach to

Developing Infrastructure Projects

III. Integrated Planning-The First Steps toward an Ecosystem Approach

Addressing Common Challenges with Locally Appropriate Strategies

"Progress begins with the belief that what is necessary is possible."

- Norman Cousins

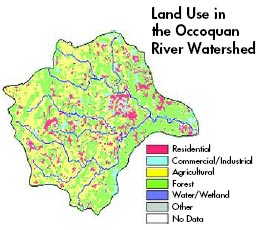

An overlay of maps can show how planned projects and objects might cumulatively impact a region's resources, as well as how these resources may shape how projects are implemented. As maps are overlaid and plans compared, priorities and opportunities for environmental stewardship and conservation of aquatic and terrestrial habitat can be identified. (Photo obtained from the Northern Virginia Regional Commission, © 2001 AirphotoUSA, LLC, All Rights Reserved.)

Integrated planning is the foundation for an ecosystem approach to infrastructure development, as well as for any ecosystem-based mitigation agreements. It allows for the formation of open dialogue and mutual objectives. Achieving joint goals requires planning that recognizes agencies' respective missions and considers stakeholders' needs.

Integrated planning attempts to provide a method for the collection, sharing, analysis, and presentation of data contained in agencies' plans. Through the collaborative efforts of field-level experts, partners, and the public, one framework outlining locally appropriate strategies can be devised (See A Framework for Integrated Planning below).

Some challenges to adopting integrated planning include:

- Conflicting priorities and scales among agencies or field offices, or national, regional, and local concerns;

- Inconsistent terminology and incompatible data and performance measures across agencies;

- Conflicting geographic, ecological, and political boundaries;

- Lack of plans, or plans with differing levels of detail;

- Communication among stakeholders;

- The need for early and long-term involvement;

- Funding procedures (short-term objectives often get funded before long-term objectives);

- Risk aversion and lack of trust among agencies;

- Belief that regulations are inflexible; and

- Political pressures (e.g., mitigate to complete this project in my district). Specific examples of stumbling blocks identified by the Steering Team include: infrastructure expenditures - highway trust fund expenditures, for example - have many priorities other than large scale ecosystem conservation; and resource agencies may not determine or share their highest priority resources until triggered and/or identified by infrastructure agencies' environmental review process.

Collaboration is key to overcoming these challenges. Many States have already formed expert-partner-public groups, and their efforts should continue to be encouraged. These groups provide the foundation and perspective necessary to broaden the context in which agencies' work is done. By going a step further to integrate plans, existing and new groups can establish and solidify common, long-term goals while making better and more inclusive decisions.

A Framework for Integrated Planning

An eight-step framework for integrating interagency planning efforts is presented below. This framework can be modified to accommodate the unique situations and various starting points at which States find themselves. Although the path may vary, in most cases, integrated planning will be an iterative process that builds on the pursuit of common near-, mid-, and long-term activities. Through each iteration, the rationale for future planning and development decisions is strengthened and the responsiveness to both infrastructure and ecosystem needs is improved.

1. Build and Strengthen Collaborative Partnerships: A Foundation for Local Action

Collaborative partnerships among diverse groups help to identify where interests and concerns overlap, and thus help to form the basis for an integrated planning process. Such partnerships can begin to be assembled today, and the effects can be both immediate and long-term.

Any agency - not just an action agency - should be able to initiate or be willing to participate in this effort. To start:

- Identify and Contact Counterparts in Other Federal Agencies

Contact counterparts to learn about their project work. Develop an understanding of their knowledge and expertise. Establish regular communication channels for interagency interaction through periodic meetings, Internet message boards, and/or peer exchanges, for example. Determine existing interagency relationships and available data.

- Build Relationships with State, County, Municipal, and Tribal Partners

State, county, municipal, and tribal partners can participate in long-term landscape conservation and management measures. They offer important services and knowledge and have significant project and mitigation implementation concerns.

- Include the Public and Determine other Stakeholders

Federal agency staff should act as catalysts for greater and more transparent public and stakeholder participation. By encouraging the early and frequent involvement of all stakeholders throughout the planning process, community concerns can be more fully integrated into decisions. Their involvement can prevent conflict and contribute to creative resolutions if conflicts do arise.

- Formalize Partnerships

Cooperating agencies and organizations can consider formalizing working partnerships. One way to document partnerships is to create an MOU. These agreements outline upfront roles and responsibilities and help to ensure balanced and nonpolarized commitment.

Back

2. Identify Management Plans: A Foundation for a Regional Ecosystem Framework

The next step is to identify management plans that agencies and partners have developed individually. These plans are important sources of information in the integrated planning process. Some types of plans include: recovery plans; resource management plans; forest management plans; USACE's Special Area Management Plans (SAMPS); and community growth plans. Map products from gap analyses and Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) plans—such as the Bird Conservation Plans of Partners In Flight and the ecoregional plans of The Nature Conservancy—are also relevant plans.

A valuable plan that identifies wildlife and habitat conservation priorities, opportunities, and needs in a planning region is a State Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy, also known as a Wildlife Action Plan. (See Wildlife Action Plans below.) To be eligible to receive Federal funds through the State Wildlife Grant (SWG) program and Wildlife Conservation and Restoration Program (WCRP), each State and territory will have developed a Wildlife Action Plan by October 1, 2005, as charged by Congress. A Wildlife Action Plan addresses the conservation of a broad range of wildlife species by identifying their associated habitats and the actions needed to protect and restore the viability of those habitats. The strategies, which focus on the species in greatest need of conservation while addressing the needs of the full array of wildlife in each State, can provide a baseline assessment or inventory of current wildlife and habitat resources. They also can give agencies and conservation partners the information necessary to strategically think about both individual and coordinated roles and responsibilities in conservation efforts.

In coastal States, in particular, there will be additional management plans to incorporate that deal specifically with important marine and coastal issues. Examples include (but are not limited to) plans from: State coastal management programs, State coastal nonpoint pollution programs, National Marine Sanctuaries (NOAA Fisheries Service), National Estuarine Research Reserves (NOAA Fisheries Service and States), and National Estuary Programs (EPA). Additionally, fishery rebuilding plans and recovery plans for living marine resources should be included, where appropriate (NOAA Fisheries Service and State fisheries agencies).

Watershed Planning: Occoquan Water Supply Protection

In the mid-1980s, several counties in a rapidly urbanizing area of Virginia developed a comprehensive land use plan for the Occoquan Reservoir watershed and adopted zoning ordinances regulating the location, type, and intensity of future land uses. This was done after maximizing the limits of treatment technology for the wastewater treatment plants discharging into the tributaries upstream of the reservoir and after intensive data collection and model development. Fairfax County took the lead in working with basin partners to study different land use development scenarios and how well they met multiple objectives such as:

- Improved transportation system

- Economic development

- Efficient provision of community services

- No degradation of the Occoquan water supply.

Depending on the sensitivity of land areas in meeting specific objectives, portions of the watershed were strategically upzoned and others downzoned.

In addition, watershed plans can provide a better understanding of the health of aquatic resources. Some watershed planning groups convene to address chronic problems such as degrading fisheries, while others seek to address acute problems such as contaminated mine drainage or heavy erosion along stream banks. Still other planning efforts may bring together citizen groups with local and State agencies to work on plans for community and environmental improvements. Watershed plans should consist of several components, including the identification of broad goals and objectives; a description of environmental problems; an outline of specific alternatives for restoration and protection; and documentation of where, how, and by whom these action alternatives will be evaluated, selected, and implemented.

For transportation, the Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) or Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) states how the region plans to invest, both long-range (over 20 years) and short-range, in the development of an integrated intermodal transportation system. Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) make special efforts to engage interested parties in the development of this plan. Additionally, the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) is a financially constrained, three-year program covering the most immediate implementation priorities for transportation projects and strategies from the LRTP or MTP. It is a region's way of allocating its limited transportation resources among the various capital and operating needs of the area, based on a clear set of short-term transportation priorities. The TIP is incorporated into the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), a plan that lists high-priority projects that will be approved by the FHWA and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) to utilize Federal funds.

Wildlife Action Plans

Under the State Wildlife Grants (SWG) Program and the Wildlife Conservation and Restoration Program (WCRP), each State has a Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) - or Wildlife Action Plan - in place. The Strategies, which have been developed in consultation with local stakeholders and reviewed by a National Advisory Acceptance Team, set a vision and a plan of action for wildlife conservation and funding in each State. While fish and wildlife agencies have led the Wildlife Action Plan development process, the aim has been to create a strategic vision for conserving the State's wildlife, not just a plan for the agency.

What information does a CWCS include?

The strategies have been developed according to requirements laid out by Congress for the WCRP and criteria developed by the USFWS for the SWG Program. Each State's Wildlife Action Plan will include information on priority wildlife species and habitats, the issues that need to be addressed to restore the viability of those species and habitats, and recommendations for addressing those issues. The Wildlife Action Plans have been developed by pulling together a wide range of available data and recommendations from other planning efforts.

Other requirements include:

- Information on the distribution and abundance of species of wildlife, as the State fish and wildlife agency deems appropriate, that are indicative of the diversity and health of the State's wildlife;

- Descriptions of locations and relative condition of key habitats and community types essential to conservation of species identified in item 1;

- Descriptions of problems, which may adversely affect species identified in (1) or their habitats, and priority research and survey efforts needed to identify factors, which may assist in restoration and improved conservation of these species and habitats;

- Descriptions of conservation actions proposed to conserve the identified species and habitats and priorities for implementing such actions;

- Proposed plans for monitoring species identified in (1) and their habitats, for monitoring the effectiveness of the conservation actions proposed in (4), and for adapting these conservation actions to respond appropriately to new information or changing conditions;

- Descriptions of procedures to review the strategy at intervals not to exceed 10 years;

- Plans for coordinating the development, implementation, review, and revision of the plan with Federal, State, and local agencies and tribes that manage significant land and water areas within the State or administer programs that significantly affect the conservation of identified species and habitats; and

- Provisions to provide an opportunity for public participation in the development of the Strategy.

Source: 16 USC 669c(d); 66 Fed. Reg. 7657 (2001)

What does a Wildlife Action Plan look like?

While the Strategies are built around a core set of planning requirements, they each reflect a different set of issues, habitats, management needs, and priorities. The States have been in partnership with the USFWS to ensure nationwide and regional consistency and a common focus on targeting resources for conserving declining wildlife and their habitat. However, the specific content and structure of each state's Strategy varies greatly. To identify how to integrate each State's Wildlife Action Plan recommendations and information at the scale appropriate to a particular Regional Ecosystem Framework, see "Integrate Plans," the third step in Integrated Planning.

Copies of each State's Wildlife Action Plans, overview and summary information, and contacts for each agency can be found at https://www.fishwildlife.org/afwa-informs/resources/blue-ribbon-panel.

|

Back

3. Integrate Plans: Creating a Regional Ecosystem Framework

To identify what work is desired and where it will be done, a regional ecosystem framework (REF) will be needed. Although there is no standard for creating a REF, Eco-Logical recommends that a REF consist of an "overlay" of maps of agencies' individual plans, accompanied by descriptions of conservation goals in the defined region(s). A REF can afford agencies a joint understanding of the locations and potential impacts of proposed infrastructure actions. With this understanding, they can more accurately identify the areas in most need of protection, and better predict and assess cumulative resource impacts. A REF can also streamline infrastructure development by identifying ecologically significant areas, potentially impacted resources, regions to avoid, and mitigation opportunities before new projects are initiated.

Since ecosystems do not necessarily follow political boundaries, REFs can cover multi-State regions. Agencies and planning partners should define, case-by-case, the region for which a REF will be created.

The following steps can assist in REF development.

-

Overlay Maps

To start, overlay maps of infrastructure and conservation plans to determine the projects and resources that "link" agencies. An overlay of maps can show how planned projects and objectives might cumulatively impact a region's resources, as well as how these resources may shape how projects are implemented. In the example below, Map A shows potential conservation areas on a base map developed by one statewide planning process. As other maps are overlaid and plans compared, priorities and opportunities for environmental stewardship and conservation of aquatic and terrestrial habitat can be identified (see Map B).

Although not all agencies will have equally developed maps or plans, this should not prevent their involvement. All agencies can contribute to the planning overlay.

|

Conservation Opportunities and Transportation Improvements in Oregon

Map A presents the locations of Oregon's conservation opportunity areas, while Map B illustrates Oregon's roads and cites, as well as its Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) overlaid. Thus, Map B shows where planned transportation improvements are located in relation to potential locations for meaningful conservation. This is one type of planning overlay—where conservation plans are extended to include transportation plans and vice versa—that Eco-Logical is encouraging. Note: This does not represent any methodology of Oregon DOT. Defenders of Wildlife created the maps below to show how these types of information could be used for comparison. Source: Defenders of Wildlife

|

|

|

| Map A: Oregon's conservation opportunity areas |

Map B: Oregon's STIP overlaid on map of

conservation opportunity areas and roads/cities |

- Define Region

With plan maps overlaid, define the region(s) to which the REF will be applied. This key step is a near-term action that can be addressed today. Agencies' approaches to defining a region differ across the country, and boundaries can be defined by a number of geo-political, socioeconomic and/or biological factors. When creating a REF, boundaries not relating to ecological resources, such as political or jurisdictional boundaries, can be addressed while providing for inter-regional coordination to address broader zones, areas of overlap or gaps, and issues of scale.

- Describe the Regional Ecosystem Framework in Writing

There is no standard for creating a REF. However, Eco-Logical recommends that a REF consist of maps accompanied by descriptions of conservation goals in the defined region(s). After overlaying agencies' plan maps and defining conservation regions, as outlined above, most of the work in this step has been completed. The process of overlaying plans will have yielded new maps, while the process of defining conservation regions will have shown how proposed projects are spatially arranged in relation to ecological resources in an area. The missing step is to document in writing proposed projects, conservation opportunities, and goals. The interagency team that is overlaying plans is likely the most appropriate author of the REF, but other concerned groups, such as local agencies, conservation organizations, and landowners should be invited to participate.

Ecosystem Frameworks and Examples of Components

An ecosystem approach and framework recognizes that the natural environment and natural ecosystems are not defined by political or jurisdictional boundaries. An ecosystem approach proceeds with a priority of considering the ecosystem and its processes. States across the country have begun work related to REF planning and have taken a variety of approaches, reflecting issues of scale, information sources, existing plans, management needs, and local priorities. Examples of components within a REF could be a statewide strategy for wildlife such as Wildlife Action Plan efforts. Because Wildlife Action Plans incorporate a broad range of information on wildlife and habitat conservation needs and opportunities, they can play a central role in the development of a REF. Maps associated with each State's Wildlife Action Plan can be useful resources for overlaying plans to identify important areas and mitigation opportunities.

Maine's Beginning with Habitat

Beginning with Habitat is a habitat-based landscape approach to assessing wildlife and plant conservation needs and opportunities. The goal of the program is to maintain sufficient habitat to support all native plant and animal species currently breeding in Maine by providing each Maine town with a collection of maps and accompanying information depicting and describing various habitats of statewide and national significance found in the town. These maps provide communities with information that can help guide conservation of valuable habitats.

For additional information on Beginning with Habitat, visit https://www.maine.gov/ifw/fish-wildlife/wildlife/beginning-with-habitat/index.html.

Sonoran Desert Regional Ecosystem Monitoring

The Sonoran Institute, an organization that works with communities to conserve and restore important natural landscapes in Western North America, is partnering to create a bi-national, ecosystem monitoring framework for the Sonoran Desert. The framework, which will be implemented by multiple Federal and State agencies, research institutions, and nonprofit organizations in Mexico and the United States, will provide the structure for developing parameters and protocols, linking monitoring to adaptive management, improving data management, and reporting on the condition of the region.

The purpose of monitoring in the Sonoran Desert is to provide an assessment of ecological conditions and trends, and the social factors that may affect them, in order to identify appropriate management and policy actions. To facilitate a coordinated, cross-border, regional monitoring program, the framework will identify a suite of indicators that captures the complexities of the ecosystem, yet remains simple enough to be practically monitored by a wide range of participants.

Montana

In Montana, an interagency team collaborated to outline a technique for rapidly identifying important wildlife linkage areas along Montana's Highway 93. (Collaborators included the USDA FS; USFWS; USDOT; Montana DOT; Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks; tribal governments; Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation; GeoData Services Inc.; and the University of Montana. FS Publication #R1-04-81, Missoula, MT.) The team's report, An Assessment of Wildlife and Fish Habitat Linkages on Highway 93 - Western Montana, describes how data on varying attributes—such as vegetation type; elevation; presence of streams, lakes, and wetlands; land ownership; road-kill; and location of both wide-ranging animals and small animals with limited mobility—can be overlaid. This integrated information can help decisionmakers conclude whether a given highway segment is suitable as an area for wildlife linkage (an area of land that supports or contributes to the long-term movement of wildlife) and for which species it is likely appropriate.

This proactive analysis of linkage areas becomes especially important when project impacts are assessed and the values of wildlife and habitat-aware infrastructure projects and mitigation are assigned. For example, if an infrastructure project overlays a linkage area, the reasons that project is important can be better understood (e.g. increased connectivity and motorist safety, decreased wildlife mortality and economic cost).

Colorado

In partnership with the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), The Nature Conservancy, and Colorado State University, Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project (SREP) has launched the Linking Colorado's Landscapes campaign to identify and prioritize wildlife linkages across the State of Colorado. The goal of this work is to provide transportation planners, community leaders, and conservationists with statewide data on the habitats and wildlife corridors that are vital for maintaining healthy populations of native species.

CDOT has completed an analysis of the entire State that identified 13 key wildlife-crossing areas. Through a two-track approach, the SREP expanded upon CDOT's work to analyze connectivity needs. The first track identified both functioning and degraded wildlife corridors that are vital to wildlife populations. The characteristics and existing conditions of each identified linkage were then evaluated. The second track used a geographic information system (GIS) to layer spatial data about the physical characteristics (e.g., topography, rivers and streams) with information about wildlife habitat preferences and movement patterns. This allowed for the modeling of landscape areas key to wildlife movement. The two tracks were then combined for a cross-comparison of the highest priority linkages identified by each. The next phase in the project, Linking Colorado's Landscapes and Beyond, provided an in-depth analysis to CDOT and FHWA on each top priority linkage. Planners will use the analysis to identify wildlife needs within the top priority linkages.

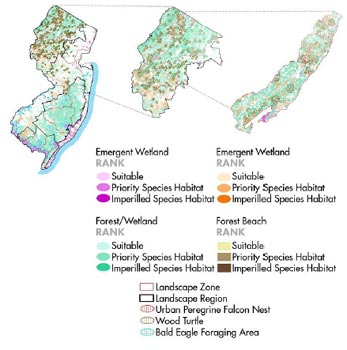

New Jersey

The New Jersey Wildlife Action Plan is built on the foundation of the State's Landscape Project, a habitat prioritization and mapping framework developed in 1994 by the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife's Endangered Species and Nongame Program. The Landscape Project identifies critical patches of five habitat types (forest, grassland, forested wetlands, emergent wetlands, and beach/dune) across five landscape regions: the Skylands, the Piedmont/Coastal Plains, the Pinelands, the Atlantic Coastal, and Delaware Bay. Information on wildlife of greatest conservation need, threats, conservation goals, and conservation strategies is linked to each habitat patch, landscape region, and landscape zone through an interactive database. |

|

Wyoming

The Wyoming Wildlife Action Plan describes the conservation status and needs of 52 terrestrial ecological systems across 7 ecoregions, aggregated into 7 major community types. By modeling the condition of habitats statewide and reviewing the current level of protection assigned to each habitat, the Wildlife Action Plan identifies which habitats have relatively greater conservation need. Habitat conservation recommendations in the Wyoming Wildlife Action Plan also integrate the Wyoming Strategic Habitat Plan (SHP), a pre-existing agency plan that identifies priority areas for terrestrial and aquatic habitat conservation and management. Future versions of the SHP will be specifically linked to Wildlife Action Plan priorities.

Illinois

The Illinois Wildlife Action Plan draws on existing conservation plans and considers the stresses affecting habitats and species in greatest need of conservation to identify conservation priorities at several scales. The Wildlife Action Plan sets 20-year goals for each of 9 key habitat categories, and describes specific priority actions at the statewide scale and for each of the State's 15 natural divisions. In addition, the plan incorporates conservation priority sites and zones, which have been identified by prior planning efforts, including planning workshops where participants selected conservation opportunity areas. All of these actions are drawn together into 7 major "campaigns" for the State's wildlife: streams, forests, farmland and prairie, wetlands, exotic species, land and water stewardship, and green cities.

|

Back

Saving Time - A Common Need

A shared advantage of integrated planning is the significant timesavings made possible by establishing and prioritizing opportunities. If agencies know beforehand where the most ecologically important areas and resources are, they can work to see that projects avoid these areas as much as possible-thus saving time during planning, scoping, and environmental review.

By understanding early on where the mitigation areas most beneficial for wildlife are located, required mitigation can be more quickly implemented, perhaps streamlining permit approval for future projects.

Finally, opportunities for ecosystem-level conservation and/or mitigation that are available now may no longer be available when a project is implemented. Increasing land costs or additional development may prohibit capitalizing on these opportunities at a later date. Act now to benefit from these opportunities.

4. Assess Effects

An early assessment of the effects of proposed infrastructure projects establishes a basis for project predictability as well as environmental stewardship. The REF relates proposed infrastructure actions to the distribution of terrestrial and aquatic habitat, or resource "hot spots." It helps agencies and partners to understand the types and distribution of proposed infrastructure projects so that potential impacts can be listed in advance of their project implementation. In terms of integrated planning, once these impacts are listed, an interagency team should describe and assess these effects.

So what happens if a planned project for an existing highway is not to be implemented until many years into the future? Can the effects of the project still be assessed? As previously mentioned, a transportation agency can outline both the scale and location of projects over a 20-40 year horizon. At this stage, it is not necessary to determine the ecosystem effects of these projects with the thoroughness of a NEPA analysis. Although agencies are accustomed to the NEPA level of detail, there should be no expectation of doing so at this point. A comprehensive NEPA analysis will occur for project decisions.

The level of detail in a REF is likely to be adequate for the early planning phase of the process. With the REF in place, agencies can deduce whether a project is likely to significantly affect important wildlife habitat areas. In turn, locations where infrastructure impacts could be avoided, or mitigation most advantageously sited, would likely be identifiable; the point could be made that spending money to redesign or relocate portions of the project or to move mitigation away from the project area is environmentally preferable.

Back

5. Establish and Prioritize Opportunities

This step combines data from steps 3 and 4 of creating a REF in order to establish and prioritize opportunities. Step 3 (Integrate Plans) helps to provide an understanding of where existing conservation areas are and where additional ones could be best located. The effects assessment from step 4 elevates awareness as to how proposed projects can impact ecologically important areas. By looking at these data together, the relative importance of a State's potential mitigation and/or conservation areas can be established and prioritized.

Conservation Assessment and Prioritization System (CAPS)

CAPS, a computer software program developed by the University of Massachusetts, is designed to assess the biodiversity value of every location based on natural community-specific models, and prioritize lands for conservation action based on their assessed biodiversity value in combination with other relevant data. The tool has been used in a pilot effort to evaluate the indirect impacts of a proposed highway project on habitat and biodiversity value for aquatic and wetland communities within the context of other development in the area. For more information, visit:www.umasscaps.org/.

Each agency and partner will likely perceive the importance of certain areas and resources differently. Agencies and partners each have varying definitions of importance, some qualitative, others quantitative. In fact, many ecological economists who have tried to value ecosystem resources and functions have encountered difficulty because ecosystem benefits accrue over such a large area to so many individuals. However, as discussed previously, each agency stands to gain from an ecosystem approach, and work toward common ground is worthwhile.

For this reason, a well-defined process is critical to creating a practical crediting and debiting system. In most cases, the valuation process and outcomes should be based on decisions made earlier in the integrated planning process by the agencies and partners. One way to avoid stumbling blocks would be to define importance based on how much a project contributes to maintaining or increasing connectivity or conservation. Another way would be to consider how a project improves predictability and transparency; a project could be regarded as more important if it raised the level of agencies' trust that commitments will be honored as negotiated (predictability) or that it enhanced public involvement (transparency).

Examples of Prioritizing Resources

As with the Wildlife Action Plan planning process, some States may already have effective processes for establishing and prioritizing the importance of ecosystem resources; examples include Florida, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Utah. (Descriptions of each follow). In these States, an interagency team could use the existing methods and apply them at a landscape level.

Florida's Wildlife Species Ranking Process

Florida's Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission developed a process that uses a point system to identify habitats of greatest conservation need. The process sums points given to biological, action, and supplemental variables to measure and rank species' statuses. Biological variables measure some facet of the species biology and indicate vulnerability to species extinction. Action variables, such as species distribution and population trend, measure the amount of knowledge regarding the species' status in Florida and indirectly indicate the extent of existing conservation efforts. Supplemental variables answer questions that help sort groups of species, for example, hunted versus nonhunted, or resident versus migratory hunted. Some variables include: population size, population trends, range size, distribution trends, population concentration, reproductive potential, and ecological specialization. Scoring and ranking of these and other species' variables is performed annually.

Similarly, University of Florida researchers used GIS to rank Florida's State roads according to overall environmental impact, producing maps to display the results of the analysis. Primary criteria influencing high-impact rankings included biodiversity hot spots, riparian systems, greenway linkages, rare habitat types, and chronic road-kill sites. The GIS model will likely help Florida DOT integrate the need to improve transportation with the need to counteract increasing habitat fragmentation by roads.

For more information on Florida's Wildlife Species Ranking Process, visit https://www.fgdl.org/metadata/fgdc_html/iwhrs_2009.fgdc.htm. Download the report on prioritization of interface zones on State highways in Florida at https://trid.trb.org/view.aspx?id=1391698.

Identifying Priority Habitats in New Mexico

The New Mexico Department of Fish and Game relied on teams of agency biologists, academics, and other outside experts to prioritize the State's habitats. The Department began by aggregating the State's known land-cover types into 82 individual habitats. These 82 habitats were reviewed by the technical teams on 13 key factors, including the importance of the habitat for priority fish and wildlife, the rarity of the habitat in New Mexico and nationally, the threats facing the habitat, and several other indicators. This review process resulted in 10 priority terrestrial habitat types and 10 priority aquatic habitat types. Terrestrial habitats included several woodlands, riparian, shrubland, and grassland communities. Aquatic priorities ranged from large reservoirs to ephemeral marshes.

Oklahoma's Species of Greatest Conservation Need Approach

Starting with outside sources that identified animal species in special need of conservation, Oklahoma's Department of Wildlife consulted with hundreds of fish and wildlife experts to develop a list of 246 species in greatest need of conservation in Oklahoma. The Department consulted with the State's Wildlife Action Plan Advisory Group to identify the following four ranking criteria:

- The percent of geographic range found in Oklahoma;

- National Heritage Inventory ranking;

- Whether there is existing Federal funding for the species; and

- Species' population trends over the past 40 years.

These criteria were applied to all the State's fish and wildlife species to identify species in greatest conservation need. To view the final list, visit https://digitalprairie.ok.gov/digital/collection/stgovpub/id/6902.

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The NPS has a long and successful history of interagency cooperation to include ecosystems extending through multiple agency jurisdictions. One example is in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The 18-million acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is composed of 2 national parks, 7 national forests, 3 national wildlife refuges, in 20 counties in 3 States, and active involvement with multiple private organizations all striving to preserve an ecosystem intact on a regional basis. Each year, the coalition collaborates to create a work plan that outlines activities for the coming year. The plan also details the "who, what, where, when, and how" of these actions and includes criteria to measure progress and assure that the greatest possible impact is being gained by contributions made.

Utah's Habitat Prioritization Approach

The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources relied on a team of agency employees, outside experts, and stakeholders to define five criteria for identifying priority habitats: abundance in Utah; threats; trends (increasing, decreasing, stable); number of Wildlife Action Plan priority species; and overall biological diversity. Each of the State's 25 identified habitat types were reviewed and scored to produce a composite ranking. The final result was a list of 10 "key habitats," some of which include riparian, shrub, grassland, wetland, aquatic, and forested habitats.

Back

6. Document Agreements

To achieve success in integrating plans, including an evaluation of mitigation opportunities, it is important to have administrative records of agreements between agencies. Agreements help ensure commitment by endorsing agencies and can help encourage flexibility in the ways the requirements and intentions of environmental regulations are fulfilled.

Agencies and their partners should not be wary of signing agreements. Authorized agreements will not and cannot supersede NEPA and/or other requirements, such as the CWA or the USFWS Coordination Act. Where agencies agree on a prioritization of wildlife habitat resources (a REF) and/or a system allowing for mitigation in these areas, for example, the NEPA process is used to analyze and disclose the effects of the agreement on any specific proposals for agency action. A documented agreement can serve as a reference point indicating that planning and decisions have a rational basis and are in accordance with applicable law.

The Ecosystem Enhancement Program launched by NCDOT and the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources will protect the State's natural resources by assessing, restoring, enhancing, and preserving ecosystem functions. It will safeguard ecosystems at the watershed level, identifying the highest-quality sites for preservation in collaboration with a network of local, regional, and State conservation organizations and compensating for the unavoidable impacts of highway construction on streams and wetlands.

Examples of Documented Agreements

Some examples of successful documented agreements that facilitate capitalizing on disappearing ecosystem opportunities are North Carolina DOT's Ecosystem Enhancement Program, The National Wetlands Mitigation Action Plan, and Colorado DOT's Shortgrass Prairie Initiative. Each is discussed below.

Memorandum of Agreement to Establish the Ecosystem Enhancement Program in North Carolina

On July 22, 2003, the USACE, Wilmington District, entered into an MOA with the North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the North Carolina DOT to establish the Ecosystem Enhancement Program (EEP). The mission of EEP is to protect the natural resources of North Carolina through the assessment, restoration, enhancement, and preservation of ecosystem functions, and compensation for development impacts at the watershed level.

The benefits of EEP can include:

- Increased protection of North Carolina's natural resources;

- Creation of mitigation strategies that are tailored to the needs of each river basin;

- Additional protection of tens of thousands of acres of ecologically important areas;

- More effective collaboration with the private sector and conservation groups; and

- Reduced cost and improved delivery of transportation projects.

In 2015, EEP changed its name to the Division of Mitigation Services (DMS). More information can be found at: https://deq.nc.gov/about/divisions/mitigation-services

The National Wetlands Mitigation Action Plan

The National Wetlands Mitigation Action Plan includes 17 tasks that 6 Federal agencies agreed to complete by 2005 to improve the ecological performance and results of compensatory mitigation. Completing the actions in the Plan will enable the agencies and the public to make better decisions regarding where and how to restore, enhance, and protect wetlands; improve their ability to measure and evaluate the success of mitigation efforts; and expand the public's access to information on these wetland mitigation activities. For more information visit: https://www.epa.gov/cwa-404/background-about-compensatory-mitigation-requirements-under-cwa-section-404.

With over 650,000 acres of right-of-way, the Kansas DOT, in cooperation with the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks, the Kansas Department of Agriculture, and Audubon of Kansas, implemented a variety of cooperative management and public information activities to help restore and promote roadside ecosystems, including the restoration of native grasses and other prairie plants along highways in the State. (Photo courtesy of Kansas DOT)

Colorado Shortgrass Prairie Initiative

The Colorado DOT's (CDOT) Shortgrass Prairie Initiative will help save one of the most imperiled ecosystems in the Nation - an ecosystem supporting more than 100 threatened, endangered, or declining plant and animal species. Shortgrass prairie makes up approximately one third of Colorado. Much of what's left is degraded because of agriculture, highways, and water projects. The Initiative emerged from a shared vision that public transportation agencies can use funds for environmental mitigation more effectively while making a significant contribution to the recovery of declining ecosystems. It is based on the concept that anticipating and mitigating long-term transportation impacts can reduce both the costs of implementing necessary transportation improvements in the future and the peril to this endangered ecosystem. Acting now to prevent the need for species protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) could streamline current consultation requirements and project-specific mitigation, and help avoid them in the future.

In April 2001, concerned scientists from a number of organizations took action to find a solution to the problem. CDOT, FHWA, USFWS, the Colorado Division of Wildlife, and The Nature Conservancy signed a partnership agreement to work with landowners and communities to preserve thousands of acres of shortgrass prairie in eastern Colorado. The Initiative will also improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the environmental measures associated with CDOT's routine maintenance activities, and it will upgrade the priority of bridge replacement and other activities on existing highways in Colorado's shortgrass prairie over the next 20 years. The Initiative will protect both listed and nonlisted species and will mitigate minor as well as major transportation impacts. It calls for predictions of transportation's potential impacts to prairie species over the next 20 years—predictions that will enable early, proactive avoidance, minimization, and mitigation efforts.

Back

7. Design Projects Consistent with Regional Ecosystem Framework

The benefits of integrated planning should be apparent at the project level. With this approach, planned infrastructure projects that go forward should not surprise resource agencies. If an action agency has been involved during REF development and is planning a project consistent with that framework, the resource agency response(s) should be predictable. Although new information about the ecosystem may have become available since the plans were integrated, site-specific project issues can be addressed as they arise (e.g., during the NEPA process); they do not have to slow down the entire project development process.

Agencies would likely need to revisit the analysis of project impacts if the answer to any of the following questions was yes:

- Are there any new endangered or threatened species in the area?

- Is there new and different information available about aquatic resource, wildlife, and/or habitat that could result in impacts that were not previously identified or addressed?

- Have the project plans changed?

- Have natural disturbances changed the region?

- For projects on National Forest System lands and other public lands, is off-site mitigation consistent with the management plans of the USDA FS, BLM, NPS, and others?

- Have there been any major changes in land ownership or land use since the project was approved?

- Have the assumptions or data underlying the REF changed enough to warrant additional public involvement?

Back

8. Balance Predictability and Adaptive Management: Measuring Performance

Predictability - the knowledge that commitments made by all agencies will be honored - is needed at the project level so resources can be allotted appropriately and schedules can be met. Predictability gives agencies assurance that progress over the term of a project can occur. However, while project development can occur over a short time frame, ecosystems typically change over longer periods. For this reason, agencies will need to work to balance short-term project predictability with long-term adaptive management.

Adaptive management offers a process to ensure that the plans developed to address the concerns of today can rise to the challenge of the concerns of tomorrow. Adaptive management involves continuously learning from the results of previous decisions in order that these decisions can be adjusted to produce even better outcomes. As new information on the changing status of an ecosystem becomes available, agencies can look beyond the project horizon to consider how that information can be applied to promote long-term sustainability; improved understanding of an ecosystem could lead to a revision of REF priorities.

To adaptively manage decisions within an ecosystem approach, performance should be measured. Performance metrics, which can help to distinguish the ecological decisionmaking process from the cost decisionmaking process , outline what constitutes ecological success. They provide the means to evaluate ecosystem status, as well as the success of actions—within some outlined range of acceptability. With agreed upon performance measures, the involved parties are more prepared to change accordingly when project problems or new opportunities are identified.

Adaptive management through performance measures is discussed in greater detail in Section V.

Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership

Southeast aquatic resources protection has taken a positive step forward with formal establishment of the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP). SARP is a coalition of State, Federal, and other conservation agencies that are committed to working together for the benefit of aquatic resources. Initiated in 2001, SARP has been meeting twice per year since that time. However, the partnership was formalized in summer 2004 through signature of an MOU among the 21 partners. The partnership's mission is: "With partners, to protect, conserve, and restore aquatic resources including habitats throughout the Southeast, for the continuing benefit, use, and enjoyment of the American people." No other such comprehensive partnership for aquatic resources currently exists in the country.

Recently, a grant proposal to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) to integrate the Statewide Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategies into SARP's Aquatic Habitat Plan was approved. Visit SARP's website at https://southeastaquatics.net/.

|

Common Integrated Planning Activities

Integrated planning can start immediately.

Arrange the pieces while moving forward.

|

| NEAR-TERM ACTIONS |

- Create a collaborative culture at the field-office level so agencies can develop ecosystem approaches in project development and ultimately integrate their planning efforts at the regional and landscape levels (e.g., use interagency liaison officers).

- Define the planning region

- Develop common goals and management decisions

- Consider comprehensive biological and socioeconomic factors in a region

- Contribute data, define data gaps, and determine how to better use incompatible data.

|

Identify opportunities - both inside and outside the traditional project delivery process for interagency cooperation that leads to ecosystem conservation. Review national and State MOUs. |

Take Action

If opportunities are identified, act on them.

Perform NEPA analysis where appropriate.

Implement decisions.

|

| MID-TERM ACTIONS |

- Perform connectivity analyses

- Review State CWCS

- Incorporate watershed plans

- Integrate and overlay agencies' various plans

- Establish and prioritize conservation opportunity areas

- Implement common units of measure and compatible information technology systems.

|

Use near-term actions as inputs into individual planning processes |

| LONG-TERM ACTIONS |

- Fully integrate environmental data. Make it standardized, scalable, and current.

|

Implement an iterative process of integrated planning among agencies. |

_________________________

In October 2004, the National Research Council of the National Academies published a report, Valuing Ecosystem Services: Toward Better Environmental Decision-Making, offering recommendations on valuing ecosystem services. Challenges to successfully integrating ecology and economics are also discussed. Committee on Assessing and Valuing the Services of Aquatic and Related Terrestrial Ecosystems. The National Academies Press. Washington, DC. To read the report, visit https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/11139/chapter/1.

Back to top