SECTION 106 OVERVIEW

THE NATIONAL HISTORIC PRESERVATION ACT AND SECTION 106

The NHPA, which became law in 1966, establishes our national policy on the preservation of historic and cultural places. The NHPA was a result of grassroots preservation efforts and recommendations of the U.S. Conference of Mayors in response to the severe impacts on historical and cultural places resulting from Federal programs such as urban renewal and construction of the Interstate Highway System.

Construction of Interstate Highway 5 transformed downtown Sacramento when it was built in the 1970s. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt.

The Section 106 review process is an integral component of the NHPA. See more information on the NHPA. The first section of the NHPA lays out its purpose, stating:

(b) The Congress finds and declares -

- the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon and reflected in its historic heritage;

- the historical and cultural foundations of the Nation should be preserved as a living part of our community life and development in order to give a sense of orientation to the American people;

- historic properties significant to the Nation’s heritage are being lost or substantially altered, often inadvertently, with increasing frequency;

- the preservation of this irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans….

The NHPA goes on to:

- Establish the ACHP. The mission of the ACHP, which is referred to in the NHPA as “the Council,” is to “promote the preservation, enhancement, and sustainable use of our nation’s diverse historic resources, and advise[s] the President and the Congress on national historic preservation policy.” The ACHP also developed the regulations for implementing Section 106.

- Provide for SHPOs in each state and territory. The SHPO is responsible for the state’s NHPA preservation program and advises and assists Federal agencies with their Section 106 compliance responsibilities.

- Establish the National Register of Historic Places (National Register) as the standard by which our nation determines if a historic and cultural place is worthy of preservation. See What is a Historic Property? for more detail on the National Register.

- Authorize Tribes to take over the functions of the SHPO on tribal lands.

Section 106 of the NHPA states:

The head of any Federal agency having direct or indirect jurisdiction over a proposed Federal or federally assisted undertaking in any State and the head of any Federal department or independent agency having authority to license any undertaking, prior to the approval of the expenditure of any Federal funds on the undertaking or prior to the issuance of any license, shall take into account the effect of the undertaking on any historic property. The head of the Federal agency shall afford the Council a reasonable opportunity to comment with regard to the undertaking.

In sum, Section 106 requires a Federal agency, such as FHWA, to 1) take into account the effects of their actions on properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register, and 2) provide the ACHP an opportunity to comment on the Federal agency’s actions. As defined in the NHPA, a property listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register is a “historic property.”

The ACHP’s regulations lay out the process and steps for how a Federal agency addresses these two requirements, and thus fulfills its Section 106 responsibilities. The heart of this process is consultation with multiple state and local agencies and organizations, Tribes, and the public.

The Section 106 regulations do not determine a specific outcome but establish a sequential process leading to a final agency decision. This decision-making process is informed at each step by consultation with SHPOs, Tribes, applicants for federal funding or approvals, local governments, and others with a demonstrated interest in the Federal undertaking. These parties are referred to in the regulations as “consulting parties.” Agency decision-making is also informed by input from the public (see Section 106 Participants: Roles and Responsibilities on the participants in the Section 106 process). As a result, the Section 106 regulations reflect the direction set by the NHPA, emphasizing the importance of balancing the competing needs of transportation project delivery and historic preservation. As highlighted in the regulations, this balance is achieved through consultation.

Further resources on the NHPA and Section 106:

- FHWA Historic Preservation Program

- ACHP Protecting Historic Properties: Working with Section 106

- AASHTO Practitioner’s Handbook: Consulting Under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (Number 6, August 2016)

STEPS OF THE SECTION 106 REVIEW PROCESS

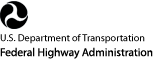

Four steps in the Section 106 review process are laid out in the Section 106 regulations as shown in the graphic.

The four steps in the Section 106 process, with key activities for each step. See full description here.

The first step is Initiation of the Section 106 Process. This step is triggered whenever there is a Federal action, such as a project funded by a Federal agency or a project that requires a Federal approval or permit. This step may result in FHWA determining that its action has no potential to cause effects to historic properties, and with this determination, Section 106 is completed. If the project does have the potential to cause effects to historic properties, FHWA initiates the first step of the Section 106 process.

Section 106 is typically triggered by the same actions that trigger National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It is important to note that although often integrated into the NEPA process, Section 106 imposes an independent legal requirement on FHWA. For more information on linking the NEPA and all of the steps below, see Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act.

The second step is Identifying Historic Properties within the area that could be affected by the project. The identification of historic properties is made in consultation with the consulting parties and the public. This step includes the delineation of the area in which historic properties have the potential to be affected by the project. This area is referred to in the Section 106 regulations as the Area of Potential Effects (APE), which is almost always larger than the project area or right-of-way (defining a project’s APE is discussed in detail in Identifying Historic Properties). If there are historic properties within the APE and they will not be affected by the project, FHWA documents this finding and Section 106 is completed. If historic properties may be affected, FHWA proceeds to the third step.

Field work is performed to identify historic properties. Here, excavation of a historic chapel site in Jamestown, Virginia. Photograph courtesy of Maryann Naber.

In the third step, Assessing if a Project Will Have an Adverse Effect on Historic Properties, FHWA assesses if the project will have an adverse effect on historic properties within the APE. This assessment is also made in consultation with the consulting parties and the public. If there are no adverse effects, the FHWA documents this finding and the Section 106 process is completed. If there will be an adverse effect on historic properties, FHWA proceeds to the next step.

The fourth and final step involves Resolving Adverse Effects on Historic Properties within the APE, in consultation with the consulting parties and the public, and the ACHP if it is participating in the Section 106 review for the project. Measures to resolve the adverse effects are set out in an agreement document, which, once signed by the participating parties, completes the Section 106 process. Though the Section 106 process is completed, the measures to resolve the adverse effects must be carried out, following the commitments in the agreement.

Steps of the Section 106 Process provides detailed information on each of these steps.

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR CARRYING OUT THE STEPS IN THE SECTION 106 PROCESS?

The FHWA has the legal responsibility for compliance with Section 106 when 1) providing financial assistance for a project or program, or 2) a project requires approval from FHWA.

The role of FHWA in the Section 106 process, in addition to the other participants in the process, is discussed in greater detail in Section 106 Participants: Roles and Responsibilities.

FHWA has the authority to make all final Section 106 decisions and findings related to the steps in the review process, except when there is a dispute involving the eligibility of properties for listing in the National Register. If FHWA and a SHPO have a dispute about eligibility or if the ACHP directs FHWA to seek a finding on eligibility, the Keeper of the National Register makes the final decision on eligibility (see What is a Historic Property? for a discussion on this exception). The Keeper is an NPS official within the Department of Interior.

FHWA’s Section 106 responsibilities and authority can, however, be delegated to a state department of transportation (State DOT) through National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) Assignment. For states participating in the NEPA Assignment program, the State DOT formally assumes the federal role in NEPA and related environmental statutes, including Section 106. For Section 106 in NEPA Assignment, the State DOT assumes full legal responsibility of FHWA and serves as the “Federal agency.” In all cases under NEPA Assignment, FHWA remains responsible for government-to-government tribal consultation. The ability to make some Section 106 findings and decisions may also be formally delegated to a State DOT through a Section 106 Programmatic Agreement. In this case, however, FHWA is still legally responsible for Section 106 findings and decisions. See Delegation of Section 106 Responsibilities for more detail.

As required in the Section 106 regulations, it is FHWA’s responsibility to ensure that activities are conducted by individuals meeting the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualification Standards (qualified professionals). FHWA Division Offices normally do not have individuals that are qualified professionals, so a Division Office will rely on the qualified professionals within a State DOT or a consultant with qualified professionals working under contract to the State DOT to make recommendations regarding eligibility and effects. FHWA uses these recommendations as the basis for its Section 106 decision-making.

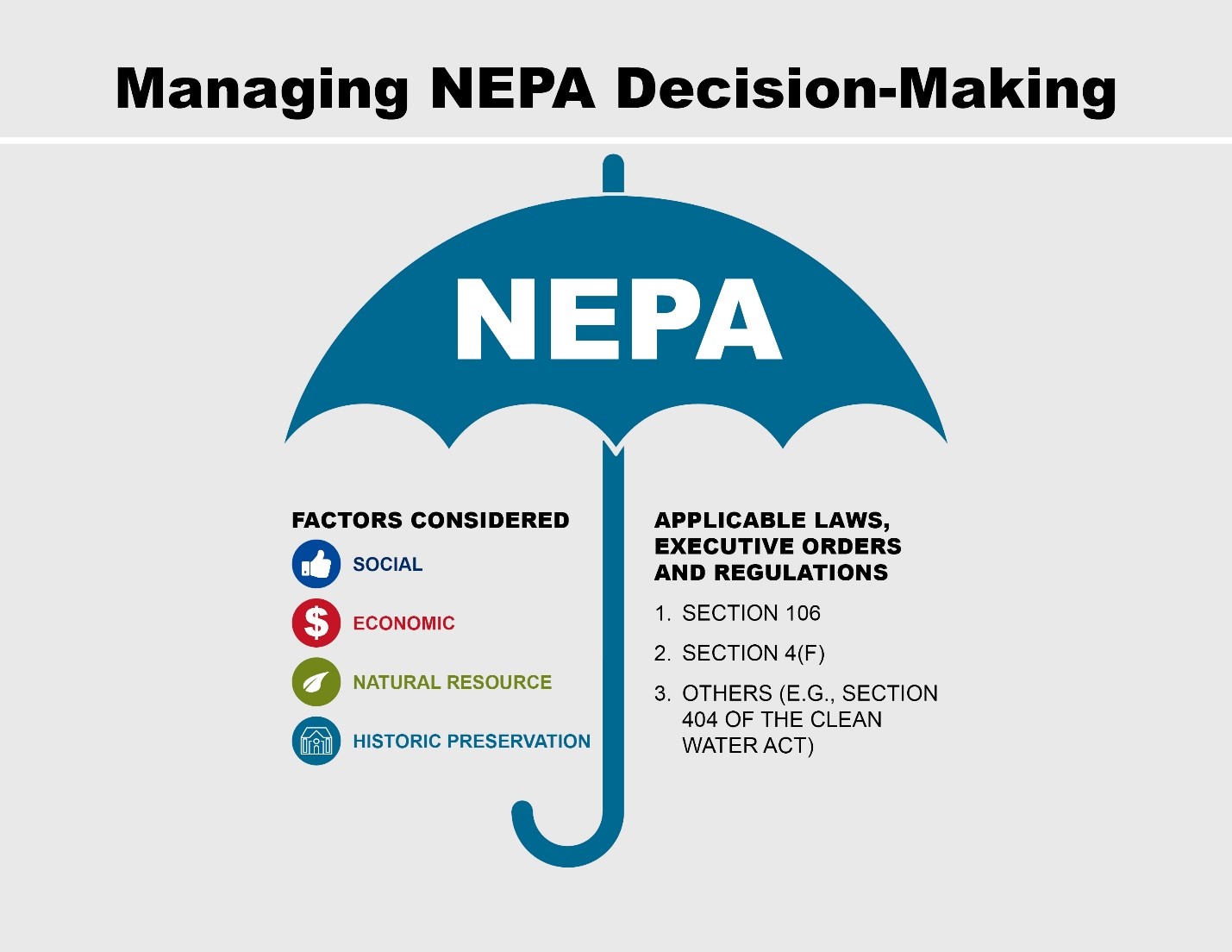

SECTION 106 IN THE CONTEXT OF FHWA’S TRANSPORTATION PROJECT DELIVERY PROCESS

Section 106 compliance is an integral part of FHWA’s environmental review conducted in support of transportation project delivery. As discussed further in Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act, it is FHWA policy to manage the NEPA review and decision-making process as an “umbrella” under which applicable laws, executive orders, and regulations, including Section 106, are considered and addressed prior to final FHWA approval of a project. This process allows FHWA Division Offices, State DOTs, and Local Public Agencies (LPAs) whose transportation projects rely on FHWA funding or approvals to make final project decisions that balance engineering and transportation needs with social, economic, natural resource, and historic preservation (i.e., Section 106) factors.

The NEPA “umbrella” showing factors considered and applicable laws, executive orders, and regulations in the NEPA process. Source: FHWA

Another one of the applicable laws under the NEPA “umbrella” is Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act. The Section 4(f) evaluation strongly influences project decision-making in terms of project alternatives and design. As discussed in Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act, properties protected under Section 4(f) include “historic sites,” which are properties listed in or eligible for listing in the National Register. In addition, Section 4(f) evaluations rely on the results of the Section 106 process when a project may affect historic sites. For more information on Section 4(f) and its role in FHWA’s transportation project delivery, go to FHWA’s Section 4(f) Tutorial.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.