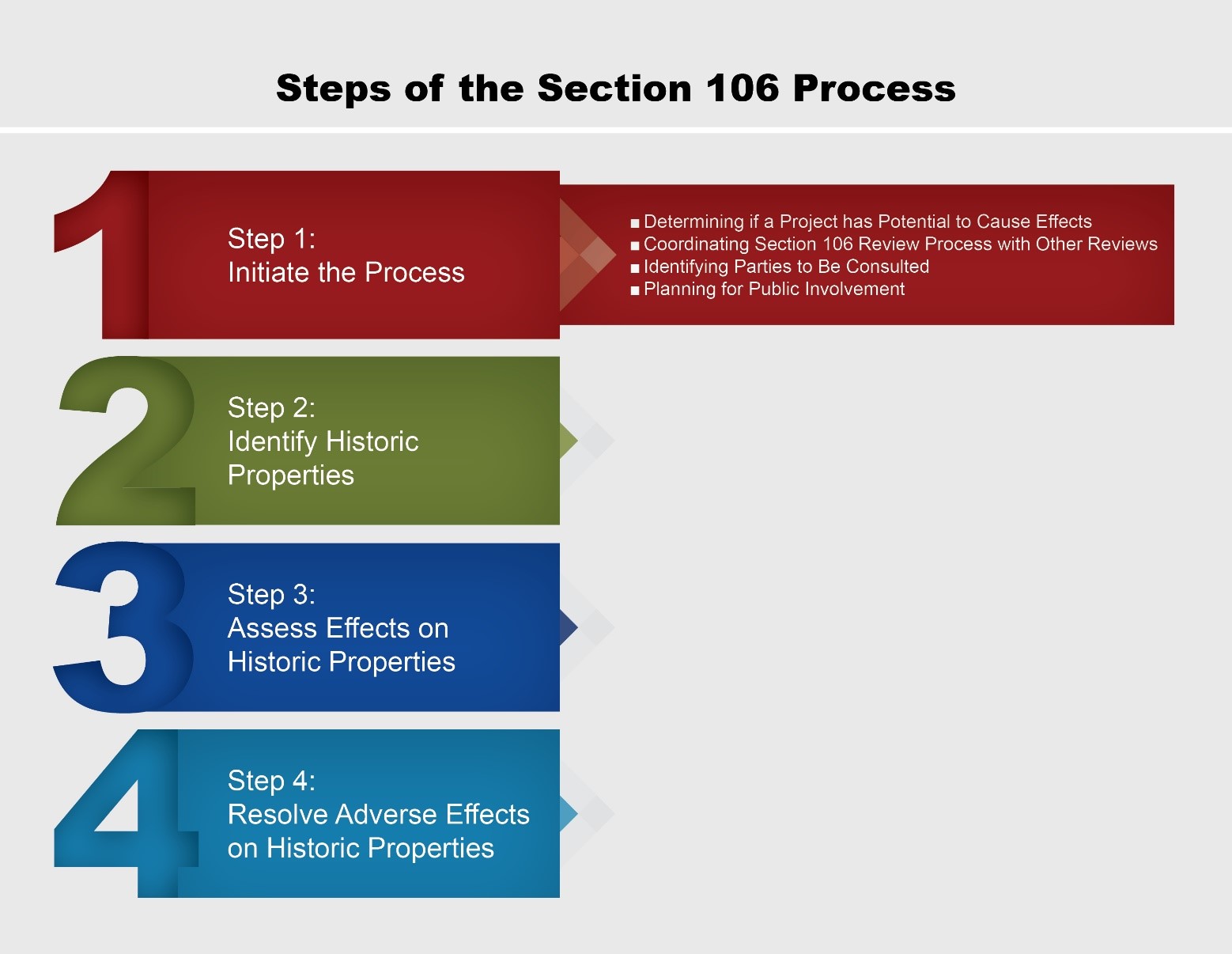

Steps in the Section 106 Process

STEP 1: INITIATING THE SECTION 106 PROCESS

The four steps in the Section 106 process, with key activities for each step. See full description here.

This first step in the Section 106 process, as noted in the regulations, consists of the following decisions and actions:

- Determining if a project has the potential to cause effects to historic properties.

- Coordinating the Section 106 review process with other statutory reviews.

- Determining if other Federal agencies should participate in FHWA’s Section 106 review process.

- Determining if a project is on tribal lands.

- Identifying the parties to be consulted during the Section 106 process.

- Planning for public involvement during the Section 106 process.

Each of these decisions and actions are discussed below.

The initiation step should be viewed as an important and early opportunity to develop a strategy, and if appropriate, a formal plan on how and when FHWA, applicants, and other parties will work together to advance an effective and efficient Section 106 review process.

Determining if a Project has the Potential to Cause Effects to Historic Properties

Initiating the Section 106 review process begins with FHWA determining if a project has the potential to cause effects to historic properties. This determination is made by the Federal agency with no consultation with other parties. The following is the definition of undertakings that have no potential to cause effects to historic properties, following FHWA policy:

Undertakings that have no potential to cause effects to historic properties, pursuant to 36 CFR [Code of Federal Regulations] Part 800.3(a)(1), are defined as those actions that by their nature, will not result in effects to historic properties. FHWA defines these actions as non-construction related activities. For example, purchasing equipment, planning, and design all fall under this portion of the regulation and do not require any further obligations under Section 106. All construction-related actions with a federal nexus must comply with 36 CFR Part 800.4 to 800.6.

If FHWA determines that a project has no potential to cause effects to historic properties, FHWA documents this decision and the Section 106 process is completed. If a project does have the potential to cause effects to historic properties, FHWA will continue with initiating the Section 106 process. Certain projects with minimal potential to affect historic properties may not be required to undergo the full Section 106 review provided they meet screening criteria established in a statewide Programmatic Agreement (PA) as described below.

Screened Projects

Several FHWA Division Offices (DOs), through their state delegation PAs, have added a decision-making point to the initiation step of the Section 106 process. This decision-making point involves screening of projects by individuals meeting the Secretary of the Interior’s Professional Qualifications Standards (qualified professionals) to determine if a project may have the potential to cause effects to historic properties, but the potential effect is minimal.

Following the requirements stipulated in a delegation PA, a qualified professional within the State Department of Transportation (State DOT) screens a project to determine if the project is a type that has minimal potential to affect historic properties. The project must also be limited to a set of activities and conditions specified in the PA. These project types are most often detailed in an appendix to a PA. See Additional Information for examples of project types and activities and conditions frequently listed in state PAs with minimal potential to affect historic properties.

If a project is one of the types listed in the PA as having minimal potential to affect historic properties, and the activities associated with the project meet the required conditions, then the project will require no further Section 106 review. The State DOT documents this decision for the project files, and Section 106 is completed. Most PAs do stipulate a time (e.g., quarterly, twice a year, annually, etc.) when FHWA and the State DOT will report to the State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO) and other consulting parties on those projects that have been screened and determined to require no further review.

If a project is not a type listed in the PA as having minimal potential to affect historic properties, or does not meet the conditions stipulated in the PA, the project requires further review, and FHWA will continue initiating the Section 106 process. See Additional Information for more resources on Section 106 delegation PAs.

Coordinating the Section 106 Review Process with Other Statutory Reviews

Section 106 reviews are an integral part of FHWA’s broader National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review. For more information on integration of Section 106 with related statues, see Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act and Section 4(f) of The Department of Transportation Act. It is FHWA policy to manage the NEPA decision-making process as an “umbrella” under which environmental laws, executive orders, and regulations, including Section 106, are considered and addressed prior to the final project decision. Other applicable laws under the NEPA “umbrella” include, for example, Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act and Section 404 of the Clean Water Act. FHWA, therefore, includes the Section 106 process within the overall NEPA review and decision-making process. By linking Section 106 steps with the requirements of these other statutes, FHWA can avoid duplication of effort and protracted consultations and coordination with Federal and State resource agencies.

FHWA, working with the State DOT or other applicant, should prepare a plan on how to coordinate the Section 106 review process with these other environmental reviews and permit requirements. This is especially important when these statutes, such as Section 4(f), may rely on the findings made through the Section 106 process. Early coordination of Section 106 and related statues is essential to avoid project delays.

Determining if Other Federal Agencies Should Participate in FHWA’s Section 106 Process

Some FHWA projects require a permit or approval from another Federal agency. Examples include a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Section 404 permit when an FHWA project will impact a wetland or stream, or approval for new right-of-way when an FHWA-funded road widening project is located on lands managed by another Federal agency, such as the U.S. Forest Service or Bureau of Land Management.

Bridges over waterways, such as this one in Indiana, will typically involve two Federal agencies with Section 106 responsibility because FHWA provides funding and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers issues a permit. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt.

Each of these Federal agencies has to fulfill its own Section 106 responsibilities in relation to its permit or approval. In situations where there are multiple Federal agencies involved in a project, the Section 106 regulations allow for the Federal agencies to designate one lead agency. The lead Federal agency acts on the behalf of the other Federal agencies to collectively fulfill the Section 106 responsibilities of all the agencies. The lead Federal agency may be the same as the lead Federal agency under NEPA or it may be different. For more on the relationship between and integrating the Section 106 process and NEPA see Related Statutes: The National Environmental Policy Act and Section 4(f) of the Department of Transportation Act.

Each Federal agency can choose to be individually responsible for its Section 106 compliance responsibilities and carry out its own Section 106 review; however, this may result in duplicative analyses, consultation/coordination, and documentation. It is much more efficient for one agency (generally FHWA for an FHWA-funded project) to take the lead, providing consistency in Section 106 decisions and findings, and expediting the overall review process.

Determining if a Project Is on Tribal Lands

There are differences in how FHWA consults with Tribes about project impacts on and off tribal lands. When a project is on tribal lands, FHWA consults with the Tribe’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO), or if there is no THPO, the designated tribal representative and SHPO. FHWA must have a Tribe’s concurrence with FHWA’s Section 106 findings, and if there is an adverse effect on historic properties on tribal lands, the Tribe is a required signatory to the agreement setting out the measures to resolve any adverse effects. It is important for FHWA to determine if a project is on tribal lands in order to plan for the required consultation with the Tribe. The timing and extent of this consultation effort should be considered in preparing the project development and NEPA review schedule.

Identifying the Parties to Be Consulted During the Section 106 Process

FHWA identifies the parties to be consulted during subsequent steps in the Section 106 process and invites them to participate in the review process. For more information, see Section 106 Participants: Roles and Responsibilities. These consulting parties include:

- SHPO and/or THPO (or SHPOs and/or THPOs if the project is within multiple states or crosses multiple tribal jurisdictions)

- Tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations (NHOs)

- Applicants

- Local governments

- Others with a demonstrated interest in the project and/or its effects on historic properties

When the project sponsor is a State DOT, FHWA should work with the state agency to identify consulting parties. State DOTs often have the most up to date list of tribal and NHO contacts, which will be of great value since personnel within tribal governments often change regularly. SHPO is also a source for identifying local consulting parties. The FHWA DO may need to work with the State DOT when a local government is the project sponsor, since these local governments often do not have the Section 106 expertise or staff to identify the appropriate set of consulting parties for their projects.

Planning for Public Involvement During the Section 106 Process

The Section 106 regulations require FHWA to seek and consider the views of the public. The extent and nature of public involvement should be based on the likely interest of the public on how a project will affect historic properties. FHWA’s plan for public involvement should be developed in consultation with the project sponsor and the SHPO or THPO. See more on How and When to Involve the Public.

One of the most effective ways to address the public involvement requirements of the Section 106 process is to integrate Section 106 public involvement with NEPA public involvement. In those cases where there is no NEPA public involvement, such as for some types of Categorical Exclusions (CEs), Section 106 public involvement may still be necessary, especially if the project has the potential to affect historic properties.

An important element of planning for public involvement is identifying approaches for informing and educating members of the public about the Section 106 process, and opportunities for the public to participate in this process. In addition, this planning effort should consider how to best engage the public, especially underserved communities.

The Chihuahuita Neighborhood Association in El Paso helped the Texas Department of Transportation engage the public in the Section 106 process for the Border West Expressway Overpass. This potluck, held at the end of the project, celebrated the unveiling of a poster and history booklet produced as mitigation for adverse effects to historic properties. The booklet is available in English and Spanish. Photograph courtesy of the Texas Department of Transportation.

An inadequate public involvement process may cause delays if members of the public were not given adequate opportunity to participate earlier in the process and then later become engaged and have new information or concerns.

How to Document the Section 106 Process – Building an Administrative Record

It is important to document all agency Section 106 decisions, and the actions that lead to and support these decisions, as part of developing and maintaining a project’s administrative record. Though not listed in regulations as part of the initiation step, FHWA should have a plan on how the agency will maintain an accurate and up-to-date administrative record. This will allow FHWA to demonstrate that the agency has correctly carried out the Section 106 review process and has met its Section 106 responsibilities. A well-developed administrative record also enhances FHWA’s ability to defend its Section 106 decisions if challenged. In the context of this first step in the Section 106 review process, it is important for FHWA to document its efforts to identify and invite consulting parties, especially Tribes. Documentation on the screening of projects that would have minimal potential to affect historic properties also becomes part of the administrative record for the project.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.