Project Examples

RESOLUTION OF ADVERSE EFFECT

In this complex project example, FHWA and the State DOT sought to resolve adverse effects on multiple historic properties. FHWA, in partnership with the State DOT, consulted with Federally recognized Tribes and several other consulting parties to avoid adverse effects and resolve any remaining adverse effects that cannot be avoided.

Overview

The proposed project involved reconstruction of an urban interchange between two Interstate Highways originally constructed between 1969 and 1971. The current metropolitan population increased from approximately 130,000 to approximately 435,000 with high growth forecasted to continue. The proposed project was reconstruction of the interchange to safely accommodate travel demand.

With its large footprint, the project had the potential to affect many properties through direct and indirect effects, including visual impacts to historic properties if any new vertical highway elements might be considered as part of the project design. The State DOT delineated the APE to include approximately 1,500 acres that were subject to potential direct or indirect effects. FHWA consulted with SHPO on the APE and the SHPO agreed with the FHWA on the definition of the APE.

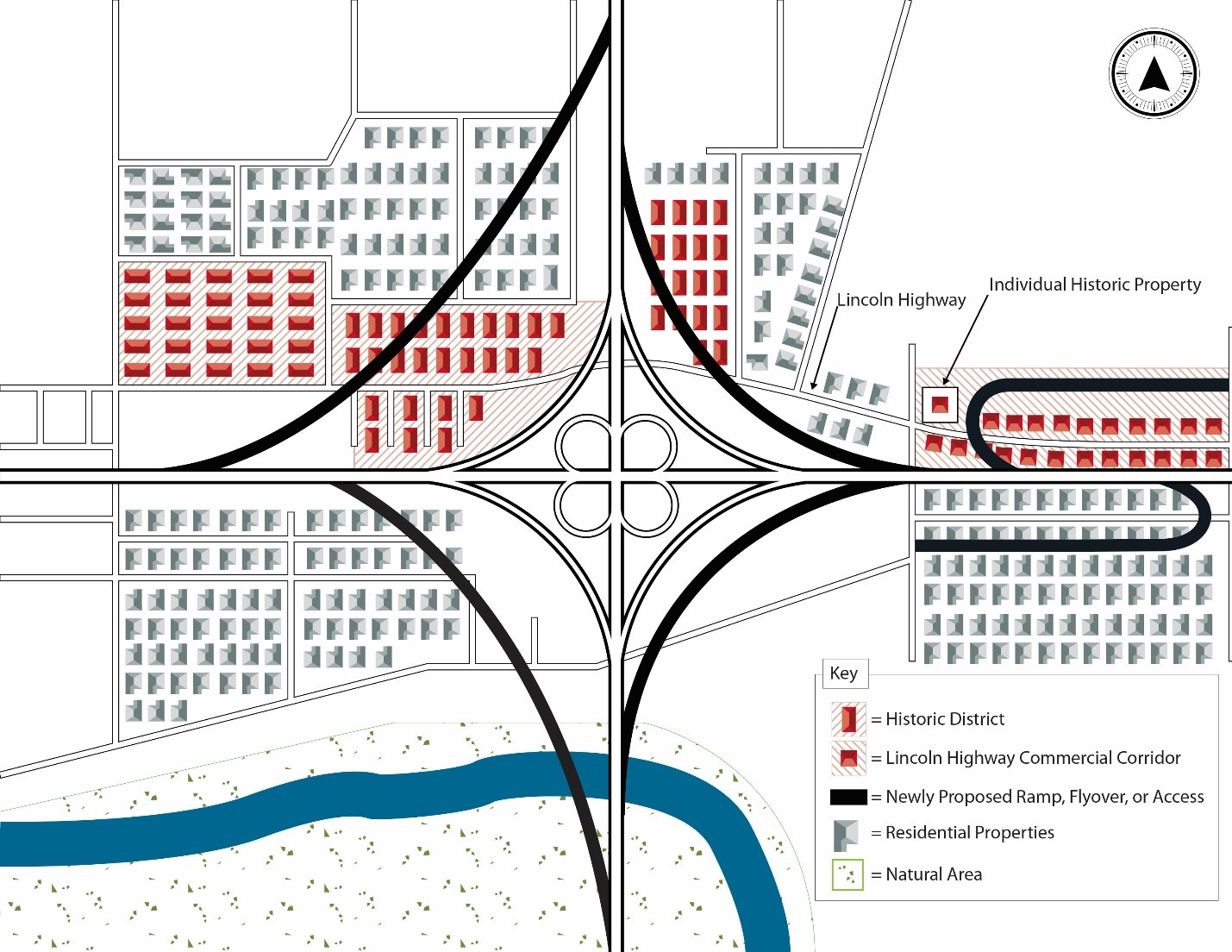

Map showing historic properties at the interchange of the proposed project.

A list of potential consulting parties was identified by FHWA, the State DOT, and SHPO and invited to participate in the project. These included Federally recognized Tribes, a Certified Local Government, businesses, residents, property owners, local units of government, historical organizations, commercial interest groups and other public entities. FHWA and the State DOT held project initiation meetings to introduce these parties to the project and provide an opportunity to comment on the range of issues that cultural resource studies should consider. The State DOT presented the project background and introduced the environmental review and Section 106 review processes, the project schedule, and provided contacts for interested parties to continue involvement. Prior to the meetings, the State DOT mailed over 13,000 letters in English and Spanish to businesses and residents within a quarter mile of the project, and to local, regional, Federal, and tribal agencies to notify them of the beginning of the National Environmental Policy Act review process, as well as the initiation of the Section 106 process.

Of the three Tribes who expressed interest and participated in the Section 106 review process as consulting parties, one Tribe had a Tribal Historic Preservation Officer (THPO). At the Tribe’s request, FHWA and the State DOT consulted initially with the THPO, while the other two Tribes requested that FHWA and the State DOT initially consult with the directors of their respective historic preservation staff. FHWA and the State DOT worked with the Tribes to address their concerns related to potential project impacts on any properties of religious and cultural significance that may be eligible for listing in the National Register.

Identification of historic properties

Archaeological investigations began with a literature review and research of historical documents and maps. This review and research identified areas of high potential for significant archeological sites dating to the city’s early European settlement. Project planners modified the design where possible to avoid these areas of high archeological potential. Qualified professional archaeologists then conducted investigations of areas within the APE where ground disturbance could not be avoided. At one location, archaeological investigations identified numerous intact features and materials dating to the city’s early-eighteenth-century settlement and nineteenth-century commercial development. FHWA and the State DOT determined that the site was eligible for listing in the National Register and SHPO concurred with this determination. This site was within the footprint of new ramp construction and could not be avoided through redesign.

Archeological investigations within the footprint of piers for a newly proposed ramp identified evidence of the city’s early European settlement. Photograph courtesy of the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Within the APE, a survey conducted by qualified professional historians identified more than 650 single-family residences located in several post-World War II subdivisions, a National Register-listed 1950s affordable housing project, and several alignments of the historic Lincoln Highway. Historians used a streamlined approach to evaluate the post-World War II residential subdivisions as districts based on the Transportation Research Board’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 723: A Model for Identifying and Evaluating the Historic Significance of Post-World War II Housing. Another existing study, the National Park Service Multiple Property Documentation Form of the Lincoln Highway in the state, allowed for an efficient evaluation of the segments of the Lincoln Highway within the APE. Portions of the Lincoln Highway and adjacent road-related resources formed several historic districts. The postwar residential subdivisions were also recommended eligible for the National Register as historic districts.

Representative streetscape of postwar subdivisions in the project APE. These were evaluated and determined eligible using a streamlined approach to evaluate post-World War II residential subdivisions as documented by the NCHRP. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt, Inc.

Lincoln Highway segment, a linear historic resource within the project area. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt, Inc.

Qualified professional historians evaluated properties in the APE and FHWA determined their eligibility for the National Register. This included individual resources and historic districts. For example, Colonial Manor, the first affordable housing project in the city, was built in 1958 and consists of an administrative building, childcare center, and 72 identical duplexes. The district is listed in the National Register under Criterion A for its direct association with early post-World War II trends in public housing. Other individual historic properties in the APE include residences, a public school, and commercial properties. One historic commercial property is the 1920 Coney Island Bar, which was determined eligible under Criterion A for its association with the city’s Italian community and role as a center for social gatherings and commerce within that community for nearly a century. FHWA made eligibility determinations for the newly evaluated properties and districts, and SHPO concurred with the determinations.

This 1950s housing project is listed in the National Register as a historic district and consists of 74 buildings, including an administrative building, childcare center, and 72 duplexes. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt, Inc.

The 1920 Coney Island Bar is eligible under Criterion A for its direct association with the city’s Italian community and its role as a center for social gatherings and commerce within that community for nearly a century. The project had an adverse effect on this historic property. Photograph courtesy of Mead & Hunt, Inc.

Consultation with the Tribes resulted in the identification of one property of religious and cultural significance to one of the Tribes: this involved both sides of a river extending through the APE. The other two Tribes did not identify properties of religious and cultural significance to them within the project APE. FHWA, in consultation with the one Tribe, determined that the property they identified was a site eligible for listing in the National Register. (Note: properties of religious and cultural significance are often referred to as Traditional Cultural Properties (TCP); however, this is a term of art and is not a formal National Register designation).

Issues considered

The FHWA and State DOT navigate a myriad of issues in conducting Section 106 for this complex project, including:

- The large number of historic properties.

- Extensive public involvement and consultation with a wide variety of interest groups.

- Consultation and consideration of multiple alternatives to find best combination that meets purpose and need and has least impact on cultural resources.

- Robust consultation with several Tribes beginning at project initiation, and then working with the Tribes to identify properties of religious and cultural significance that may be affected by the project.

FHWA and the State DOT considered three alternatives that would each require alteration of existing freeways, roads, and intersections; new vertical lanes; and right-of-way acquisition. Project design development and consultation with the consulting parties centered around finding an alternative that met the project’s purpose and need and had the least impact on historic properties. FHWA and the State DOT presented the alternatives to the public during a second meeting to which the Section 106 consulting parties were also invited. Topics for this meeting included discussion of alternatives and the environmental studies being completed, including those done for Section 106.

FHWA and the State DOT held separate meetings with each of the Tribes. At the meetings with the two Tribes that did not identify properties of concern within the APE, FHWA and the State DOT asked the Tribes to confirm that the three alternatives did not affect properties of religious and cultural significance to them. The Tribes confirmed that this was the case. During the meeting with the remaining Tribe, FHWA and the State DOT showed the Tribe that the three alternatives were designed to avoid the one property of religious and cultural significance to the Tribe. The Tribe agreed that the alternatives did avoid the property. FHWA subsequently consulted with SHPO on the findings related to the one National Register-eligible property of religious and cultural significance, and SHPO concurred that the property would not be affected by the project.

Resolution of adverse effects

Consultation among the various consulting parties helped inform selection of an alternative by FHWA and the State DOT that avoided adverse effects to most historic properties identified through the Section 106 process. The preferred alternative ultimately chosen by FHWA and the State DOT included new three-level flyovers, with new ramps to connect the Interstate Highways and widened lanes to increase capacity. Ten adjacent service interchanges would include lane marking changes and widening within the existing right-of-way to integrate with the new interchange. Adverse effects to most historic properties were avoided through refinements to the alignment and connection of flyovers and ramps.

Adverse effects to two historic architectural properties and one archaeological site could not be avoided. The Coney Island Bar, a commercial historic property, would need to be demolished and the project required land acquisition and demolition of one contributing resource within the public housing historic district. The archeological site would be impacted by the construction of piers for a new ramp. Archeological data recovery and a technical report on the data recovery were the primary measures to resolve the adverse effect to this eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archeological site.

Archeological data recovery revealed the foundations of a house dating to the eighteenth century. The darker soils where the archeologist is working are the remains of wood posts that formed the wall of the house. The layers of soil and materials above the wooden post remains are from later residential and commercial buildings. These layers highlight and provide important information about the early historical development of the city and the activities of its residents and businesses. Photograph courtesy of the Missouri Department of Transportation.

FHWA notified the ACHP of the adverse effect and invited the ACHP to participate in Section 106 consultation for this undertaking; however, the ACHP declined to participate in consultation. The consulting parties had reached agreement on how to resolve adverse effects and the nature of the effects did not meet the criteria for ACHP involvement, as stated in Appendix A of the Section 106 regulations.

FHWA and the State DOT posted the notice of availability for the project’s Draft Environmental Impact Statement in the Federal Register. FHWA and the State DOT then hosted a public hearing at an accessible location central to the project to gather public comments. The public notice included mention of identified historic properties and their consideration through the Section 106 process. Consulting parties were specifically invited to the public meeting. Potential effects to historic properties and proposed measures to avoid, minimize and mitigate any adverse effects were presented at the meeting. No public comments were made at the meeting regarding historic properties. (Note: this public involvement effort did not include discussion or information on the one identified property of religious and cultural significance given confidentiality requirements associated with properties of importance to Tribes.)

Outcome

Through consultation, treatment measures were found to appropriately mitigate the adverse effects that could not be minimized through design. After agreeing on measures to address the remaining adverse effects to historic properties, FHWA executed a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with SHPO, the State DOT, and other consulting parties.

In addition to conducting data recovery at the archeological site, the following agreed-upon measures were included in the MOA:

- Artifacts from the archeological site will be displayed at a local museum.

- Educational materials on the archeological site and the early history of this part of the city will be developed for local schools.

- The city’s website will include a story board on the history of the archeological site and how this history was revealed through archeology.

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) Level II Documentation for the public housing historic district and the Coney Island Bar will be conducted, following the National Park Service’s guidance.

- A property-specific visual and narrative history on the two historic architectural properties will be developed. It will be incorporated both into a learning module for elementary-age students and an online walking tour, developed in partnership with a local preservation organization.

MOA commitments and responsible parties were documented in the Final EIS/Record of Decision for the project, and the State DOT will be responsible for monitoring fulfillment of these commitments.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.