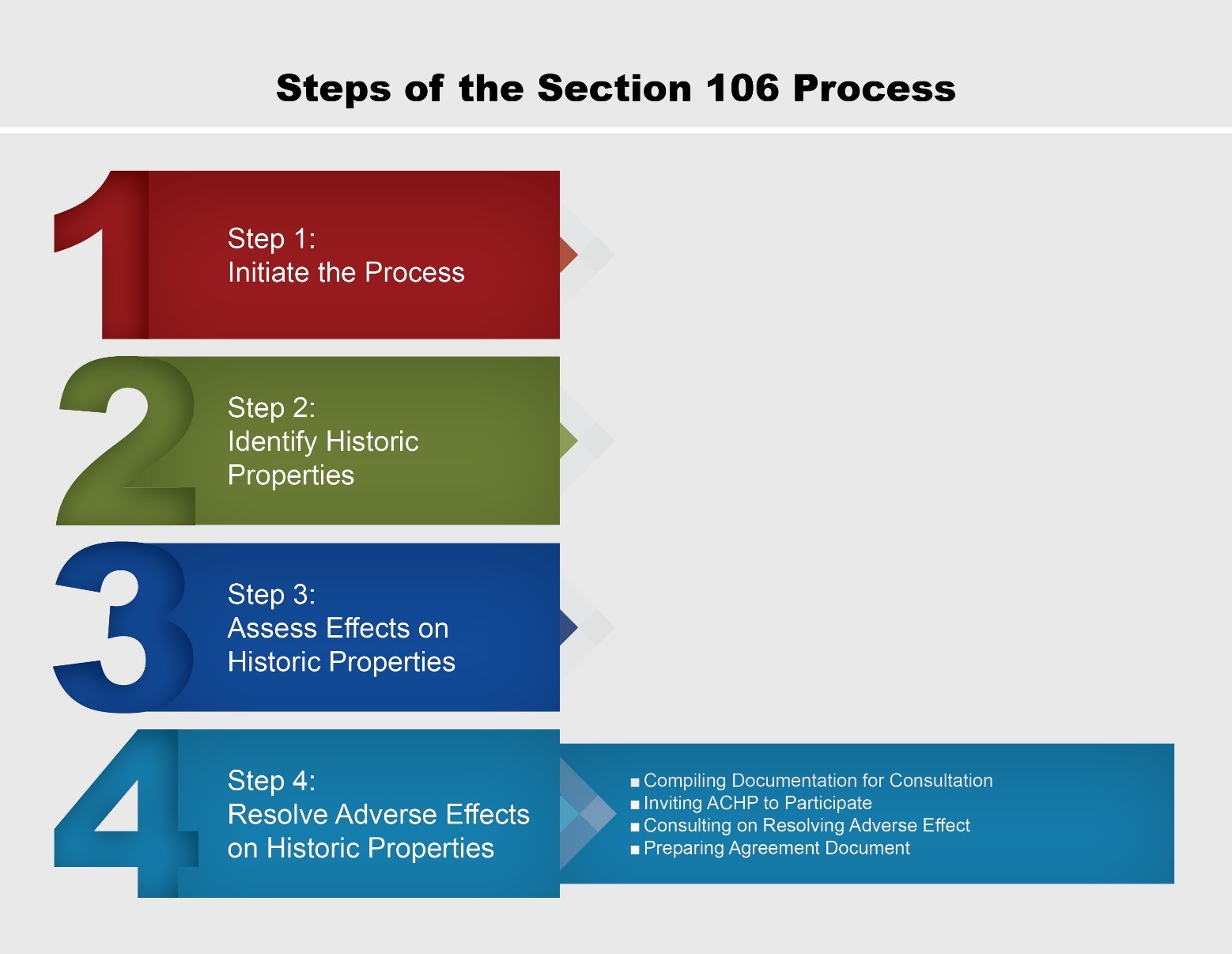

Steps of the Section 106 Process

Step 4: RESOLVING ADVERSE EFFECTS ON HISTORIC PROPERTIES

Step 4 of the Section 106 process is resolving adverse effects on historic properties. See full description here.

Under this final step in the Section 106 process, FHWA consults with SHPO/THPO and other consulting parties, including Tribes, applicants for Federal funding or approvals, local governments, the public, and the ACHP as appropriate, on how to resolve adverse effects identified at Step 3. If FHWA and SHPO/THPO agree on treatments or measures to address the project’s adverse effects, they would develop and execute an MOA, or, when appropriate, a project-specific PA. Agreed upon treatments and measures to resolve adverse effects are also included in the NEPA decision document.

Resolving adverse effects involves the following actions:

- Preparing and distributing the documentation for consultation

- Notifying the ACHP and consulting parties of the adverse effect

- Negotiating measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse effects

- Preparing the agreement document

- Securing agreement signatures and concurrences

- Filing agreement with the ACHP

- Carrying out provisions of the agreement document

A project example is provided to illustrate the resolution of adverse effects.

Documentation for Consultation

FHWA will provide the documentation for consultation specified at 36 CFR Part 800.11(e) to all consulting parties, whether “by-rights” consulting parties or invited consulting parties. The Federal agency should also make the documentation available to the public, subject to confidentiality provisions. Section 106 documentation may be distributed to the public by including it as part of the NEPA documentation provided to local outlets for public review, published online, or through other platforms and venues used in NEPA public involvement. Efforts to involve the public are usually commensurate with the scale and nature of the undertaking and may be influenced by experience with similar projects and expected interest in the project or the historic properties involved. During this step FHWA should provide an opportunity for members of the public to express their views on resolving adverse effects. FHWA should note the opportunities provided, and the resulting public input received, in the administrative record. See Guidance for Documentation for Consultation in Additional Information for more information on requisite content.

Participation of the ACHP

FHWA is responsible for notifying the ACHP when a determination of adverse effect has been made and for providing the requisite documentation for consultation to the ACHP. See Advisory Council on Historic Preservation for more on the ACHP’s role. In certain instances, the ACHP must be invited to participate in consultation. These cases include when the undertaking may have an adverse effect on an NHL or when a project-specific PA is being proposed to address the project’s effects. The latter case usually applies to a more complex project or one that involves deferred identification of historic properties and assessing effects on these properties (an example is provided in the Project Examples. FHWA may also choose to invite the ACHP when the agency seeks active participation by the ACHP due to the nature of the project, such as with controversial or complex projects. The ACHP’s decision to participate in consultation is guided by the ACHP’s Criteria for Council involvement in reviewing individual section 106 cases found in Appendix A of the Section 106 regulations.

The ACHP has 15 days to respond to FHWA’s invitation to participate, by providing written notice to the agency official, usually FHWA’s Administrator. If FHWA has not received a reply after 15 days, it may proceed with consultation without the ACHP. However, if there are concerns about the progress of consultation to resolve adverse effects, SHPO/THPO or another consulting party may at any time request that the ACHP step into the process in an advisory capacity or full participation role.

Other Consulting Parties

Any party that would be assuming a specific role or responsibility in carrying out proposed measures to resolve adverse effects must be invited to participate in the consultation; other organizations or individuals who were consulted during the previous steps in the Section 106 process may be invited to participate in the consultation to resolve adverse effects.

The Consultation Process

FHWA consults with SHPO/THPO and other consulting parties to seek ways to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse effects of the project to historic properties. Consultation may carry forward some of the measures that were initially considered in seeking ways to avoid adverse effects, such as modifications to minimize impacts to historic properties or variations in the alignment or location of the project or specific project elements. Consensus among the parties is a goal of the process in resolving adverse effects to historic properties but may not always be achievable. To ensure the process is approached and carried out in good faith, it is essential to reserve adequate time for meaningful consultation and consult the parties before decisions are made. There is no time limit spelled out in the regulations for consultation to resolve adverse effects, but it should continue as long as it is productive.

For large, complex, or controversial projects, it may be advisable to develop a formal consultation plan to help manage the process. The plan would be developed by FHWA and/or its applicants, along with input from SHPO/THPO, the applicant’s contractor, and others with an interest in the project and its effects on historic properties. The plan may address roles and responsibilities of participants, set the timing and structure of meetings, guide the development and dissemination of information, establish milestones for design development, and establish an agreed-upon framework for reviews as new information is provided. A consultation plan may also include a dispute resolution process, so the course of consultation is not unduly delayed, and guidelines for communications so project decision-makers within FHWA and the applicant’s agency are kept in the loop.

The outcome of Section 106 consultation is not predetermined. Consultation is the process of seeking input and dialogue among the participants to consider project design options that avoid or minimize effects to historic properties. However, it is not always possible to meet the needs of the project and simultaneously retain a historic property. FHWA makes the final decision about how a project will proceed. See the ACHP’s “Reaching agreement on appropriate treatment” for more information on consultation on mitigation and Additional Information on the consultation process including MOAs and PAs, and mitigating adverse effects.

Agreement Documents

Once FHWA, SHPO/THPO, and other consulting parties have agreed on the measures appropriate to resolve adverse effects, those measures are stipulated and formalized in an MOA or, in the case of a complex undertaking, a PA. Guidance is provided, explaining when each is applicable.

Memorandum of Agreement

An MOA “evidences the agency official’s compliance with [S]ection 106 … and shall govern the undertaking and all of its parts. The agency official shall ensure that the undertaking is carried out in accordance with the memorandum of agreement.” (36 CFR Part 800.6(c)).

In addition to the specific measures agreed upon to mitigate adverse effects of the project, other measures commonly included in MOAs are stipulations for reporting on implementation of the agreement’s provisions, duration for implementation, amending or terminating the agreement, and steps to be taken in the event of a late discovery of additional historic properties or effects not previously considered.

See Additional Information for more information on MOAs and mitigating adverse effects.

Programmatic Agreement

In certain situations, the document resulting from this step in the Section 106 process will be a project-specific PA. A project-specific PA may be warranted where the effects on historic properties cannot be fully determined prior to the approval of the undertaking, such as when parts of the project area are not accessible at the time of the Section 106 review, for phased undertakings to be implemented over time, or for complex projects with multiple properties and many consulting parties. In cases where a PA is used because the effects on historic properties cannot be fully determined, the PA will detail the likely presence of historic properties for each alternative under consideration or those portions of the project area that could not be investigated. The PA will establish a process to carry out appropriate levels of identification, evaluation, and treatment when possible, within these alternatives or areas. A PA may also be prepared early in the process to set expectations, guide subsequent consultation, and frame Section 106 decision-making as a project is further developed, such as with a design-build situation.

The MOA or PA itself may be written by any of the parties to the consultation but should be reviewed by all the signatory parties in advance of signing to ensure that it accurately and adequately lays out the agreed upon provisions. Specificity is important so that commitments can be clearly understood by the responsible parties. As a matter of practice for FHWA projects, the MOA or PA is often written by the applicant (State DOT) or a consultant with qualified professionals.

See Additional Information for more information on PAs and mitigating adverse effects.

Securing Signatures

At a minimum, the agreement must be signed by FHWA, SHPO/THPO, and the ACHP if it has participated in the consultation. The ACHP prefers to be the final signatory so it is fully aware of the final resolution and since the agreement will remain in its files. The roles of the parties to an MOA are:

- Signatories include FHWA, SHPO/THPO, and ACHP when participating. Signatories have the authority to execute, amend, or terminate an agreement.

- Invited signatories are additional parties invited by FHWA in consultation with SHPO/THPO and have the same rights to seek amendment to a MOA or terminate it. Applicants for Federal funds or approvals are usually invited signatories, and any party with responsibilities to carry out in its implementation must be invited to sign. By signing, these parties are committing to carrying out their assigned roles and responsibilities. A Tribe (or NHO in Hawaii) that attaches religious and cultural significance to affected historic properties off tribal land may also be invited to sign. The refusal of an invited signatory to sign does not invalidate the MOA, but if it is still acceptable to the signatory parties, the agreement should be revised to re-assign the objecting party’s responsibilities under the agreement to another party, and remove the objecting party’s signature line from the agreement. The new party is added to the list of agreement signatures.

- Concurring parties are others that have participated in the consultation to resolve adverse effects and are invited by the signatories to concur with its outcome. The refusal of a concurring party to concur does not invalidate the MOA; the MOA is considered fully executed when all the signatories and invited signatories have signed the agreement.

The all-brick Front Street in Natchitoches, the oldest permanent settlement in Louisiana, is an important part of the historic district that is recognized as a National Historic Landmark. When the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development reconstructed the road, the historic brick pavers were removed and replaced on a new construction foundation such that they are no longer used structurally. To address this adverse effect, an MOA was negotiated that included 20 stipulations, 15 of which addressed the historic bricks. Consulting and concurring parties gathered to sign of the MOA. Photograph courtesy of the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development.

Once the agreement has been executed by the signatories, it evidences FHWA’s compliance with Section 106 and completes the Section 106 review process. The executed agreement is always filed with the ACHP whether or not that agency participated. After execution, FHWA’s obligations under Section 106 are not concluded. The MOA is a legally binding document that makes FHWA responsible for ensuring its provisions to resolve any adverse effects are carried out following the commitments stipulated. If the provisions of an MOA are not carried out, or if the impacts to historic properties change as a result of subsequent changes in project design, FHWA may have to revisit the entire Section 106 process. Provisions stipulated in the MOA or PA should be included as part of the environmental commitments in the project’s NEPA document and fully funded as part of the project cost.

If the parties fail to reach an agreement during consultation to resolve adverse effects, FHWA will notify the ACHP and seek a formal resolution (see 36 CFR Part 800.7). This is rare, but if it looks like the agency is headed in this direction, the FHWA DO should contact the FHWA Federal Preservation Officer to ensure they fully understand the ramifications of this step.

See Additional Information for more information on tracking commitments made in the MOA or PA, and sample agreement documents.

For questions or feedback on this subject matter content, please contact David Clarke.